This story about school segregation was produced by The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that provides free news, data, and events on Texas public policy, politics, government, and statewide issues.

LONGVIEW — At the first Friday football game in the first school year since the school district in this East Texas town had been declared racially integrated — nearly 50 years after a federal court order — thousands of spectators dressed in forest-green Lobos gear filled the stadium.

Enduring the late-August heat, fans filed into creaky fold-down seats they’d reserved for years. Some who had attended segregated white or black schools in Longview decades ago now shared the same rows. When the marching band played the school’s fight song, most of the crowd formed an “L” with their fingers and rocked them back and forth in unison.

Ted Beard, a longtime Longview Independent School District board member, watched the football players race across the field and wondered how long the commitment to integration would last.

The district is at a pivotal moment now that a federal court has released it from decades-long supervision of its policies for educating students of color. It has made progress to topple the barriers still holding black and Hispanic students back from the same academic success as white students.Whether it continues a commitment to student equity now depends solely on the collective will of a school board that could change with a single election cycle. And that worries Beard, whose father was part of the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, in 1965 and faced threats and violence along the way. Beard is black and had two kids go through Longview schools.

“The board could change and then the direction could change, and those that are ultimately affected are going to be the students,” Beard said.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision declared school segregation unconstitutional in 1954, but Longview ISD — along with hundreds of other Texas school districts — resisted until federal judges intervened and imposed detailed desegregation plans across large swaths of the state.

In 1970, an East Texas-based federal court mandated Longview ISD tackle a long list of tasks designed to make sure its black students were learning and playing in the same classrooms and playgrounds as their white peers — including closing four all-black schools and busing black students to formerly all-white schools throughout the district.

Forty-seven years later, Longview was one of only three Texas districts that remained under a federal court order, along with San Angelo and Garland.

A federal judge fully released the district from that order in June, and just weeks before the school year started, Beard and the rest of the board unanimously approved a voluntary plan to keep the district’s schools desegregated and ensure that students of color have equal opportunities to graduate and succeed beyond high school.

But Beard and others know the district has yet to overcome the deep disparities that have defined so much of its history. In Longview ISD, white students — who make up a fraction of the district’s enrollment — still outpace their black and Hispanic peers in many ways. They are roughly half of the students enrolled at Longview’s specialized elementary school, which has higher academic standards. And they are more likely to take classes and tests meant to prepare them for college.

And district leaders also have struggled with a new education challenge that federal judges couldn’t have foreseen in 1970 — adequately providing a burgeoning group of Hispanic students with crucial services they need to learn English.

Order from the court

Sixteen years after the Brown ruling, the federal government sued the state of Texas for refusing to integrate most of its schools. In 1970, a federal judge almost 40 miles from Longview placed nearly the entire state under court order and threatened sanctions against defiant school districts — resulting in one of the largest series of desegregation orders in the nation’s history.

The same court ordered Longview to integrate both its faculty and students. That meant busing more than 600 black students to white schools and the consolidation or closure of several all-black schools. If white students tried to transfer, the court order mandated that they could only be reassigned to schools in which they would be in the minority.

Longview ISD was unlikely to have integrated without a court order. Like people in much of the state, folks in Longview saw the federal push for integration as a threat to their autonomy.

The effort to improve facilities across the district was slow. Board members began pushing to renovate some of the old school buildings in the late 90s. Since the integration order, white families — who still made up the majority of Longview’s population — had left the school district in droves for private schools, and white voters actively resisted paying to renovate the district’s schools.

“If you’re an Anglo family and you’re taking your kid out of school, why would you vote yes to float a bond?” said Chris Mack, a white board member first elected in 1993 who was a middle school student in Longview ISD when it was forced to integrate.

By many accounts, the turning point came when James Wilcox was hired as superintendent in 2007.

With Wilcox at the helm, the community approved — in a measure that passed in 2008 by fewer than 20 votes — a $266.9 million bond to finance a massive overhaul of the district’s schools. Longview ISD built eight schools, renovated three others and upgraded technology across the district.

The district made more progress integrating black students after 2008 than it had in the previous 15 years, according to an analysis of school segregation data by Meredith Richards, an assistant professor of education policy and leadership at Southern Methodist University.

While overhauling schools, the district went back to the federal court to argue that it no longer needed an extensive busing system, which district leaders argued had become tedious.

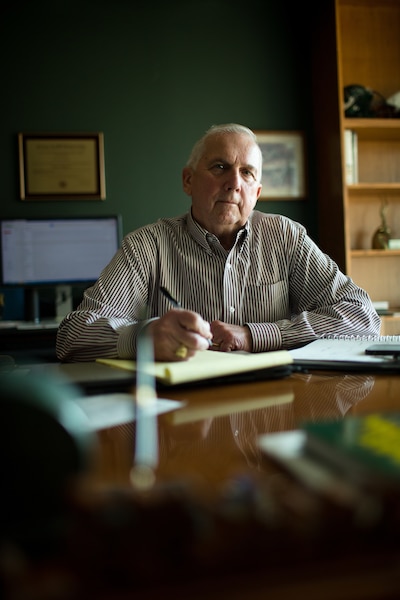

“We did what was best for our students while meeting the requirements of the desegregation order,” Wilcox said from his office earlier this year. “But it was a dinosaur, a pyramid, or whatever you want to say — something that in our mind has lost its function because it’s a totally different district.”

In 2014, the courts released the district from some of the restrictions of the original 1970 court order. In exchange, the district’s leaders promised to spend the next three years working to improve in areas where Longview still needed to make progress after more than four decades: monitoring racial disparities in student discipline, preventing students from transferring to schools where their race was the majority, hiring a more diverse staff and ensuring students of color had equal opportunity to take advanced classes.

A strategy with a Montessori in mind

Since 2017, most pre-K and kindergarten students in Longview have begun their education at East Texas Montessori Prep, a $31 million, 150,000-square-foot building in the middle of the district.

“We have the same exact expectations for every student,” Wilcox said.

Widely considered an exclusive educational program more common in private schools, Montessori prioritizes self-directed, hands-on student learning.

Troy Simmons, who became Longview ISD’s second black board member in 1985, saw East Texas Montessori Prep as a way to give students of color a competitive advantage early in their lives. Community members often responded to the district’s pitch to create the Montessori school by complaining about how much it would cost, he said.

“People don’t believe in educating all children. They believe in educating their kids, not your kid,” Simmons said.

Among the strongest objections to a district-wide Montessori school came from parents at Johnston-McQueen Elementary School, located in the whitest part of the school district, where parents successfully advocated to keep a traditional pre-K and kindergarten program for students zoned there.

To Simmons, the separate program is a figurative foot in the door, impeding the district’s plan for a cohesive education system.

If the decision had been left up to Beard, Longview ISD would not have given up court supervision at all.

His opposition is recorded in a few lines in the minutes from the November 2017 board meeting: “Knowing that at a drop of a dime the board could change and take…its sight off what is best for ALL students, he will not support this motion.”

Beard voted no, joined by Shan Bauer, who is also black.

Simmons, joined the majority in the 5-2 vote to ask the court to fully release the district — a decision he later regretted.

In June 2018, Judge Robert Schroeder lifted Longview ISD’s court order.

Another challenge emerges

The district was also confronting a new challenge that the courts in 1970 had never anticipated: Providing an equal education to an exploding population of Hispanic students — many of them immigrants or first-generation citizens, and many of them Spanish speakers.

Without a court order hanging over them, the district’s leaders, by their own admission, have struggled to lift Hispanic students like they did, belatedly, for black students.

Hispanic enrollment in Longview schools has almost doubled in the last 13 years alone. The district has included them in many of its desegregation measures, particularly in its efforts to recruit students for advanced classes, said Jody Clements, an assistant superintendent at Longview ISD.

But in Longview, most Hispanic students need bilingual or English as a second language instruction — hundreds more students enrolled in those programs between 2009 and 2017, state data shows.

The number of teachers for those programs only increased by about five.

“We haven’t cracked that nut yet,” Mack said after an August school board meeting during which the issue was discussed in executive session.

The new reality

In August, Longview’s school board unanimously approved a seven-page voluntary desegregation plan that it plans to implement with the help of a $15 million grant from the U.S. Department of Education. Starting this year, five predominately black and Hispanic schools will offer special programs, such as advanced engineering or college preparatory courses, to attract higher-income students and white students living in the district but attending private school or homeschool.

The plan is self-enforced, with no federal judge serving as referee.

Longview ISD leaders will no longer limit student transfers to certain schools based on race or set goals for the percentage of white, black or Hispanic students for each school. Instead, if they notice a school is becoming more segregated, they will correct the problem using “race-neutral” strategies, such as recruiting students from low-income neighborhoods — which some experts say is not as effective in achieving racial integration.

About 56.2 percent of white students graduated ready for college English and math in 2016, according to state data, compared with a dismal 23 percent of Hispanic students and 16 percent of black students. That disparity is similar among students who take Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate classes in high school.

Will the momentum continue?

The community’s commitment to equity could soon be tested. Though Mack was just re-elected to another three-year term, he will likely step down after handing his daughter her diploma at graduation this spring, after nearly 20 years on the board.

Simmons, who now has the longest tenure on the board, regularly considers whether it’s time to retire. He’s tired, he says, but leaving is not a decision he can make without considering the impact on Longview’s progress.

“I have a lot of faith in our superintendent. I have a lot of faith in the core of our board, the way it operates, but I also know that one change, one blip, one glitch can turn the board into something completely different and basically destroy everything that we’ve built in these past years in doing this,” Simmons said solemnly at the start of the year. “And so that makes me hesitant about not seeking re-election, but at the same time I am tired of fighting this the way I have to.”

Four months later, Simmons ran for — and secured — another three-year term.

Ryan Murphy contributed to this report.

Disclosure: Southern Methodist University has been a financial supporter of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune’s journalism. Find a complete list of them here.