The debate around school vouchers has exploded in the last year with the appointment of Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos. That also means recent studies showing that student achievement drops, at least initially, when students use public dollars to attend private schools have gotten a lot of attention.

But supporters have countered that test scores only say so much about student performance. The real test is how students do over the long term.

Two studies out Friday offer new answers — and some ammunition for both sides.

The research looks at how students from Milwaukee and Washington, D.C. fared after using a voucher to attend private school. It found students in Milwaukee’s voucher program were more likely to attend four-colleges, but not necessarily more likely to actually graduate. In D.C., voucher recipients were no more likely to enroll in college.

Here’s what else the studies tell us.

Disappointing results for D.C. voucher program

The D.C. analysis, conducted by Matt Chingos of the Urban Institute, found that 43 percent of students who won a voucher enrolled in college within two years of graduating high school. That’s 3 percentage points lower than similar students who lost the lottery, though the difference was not statistically significant.

The research relied on that random lottery for allocating vouchers in the first two years of the program. This meant the study could confidently show that any difference between lottery winners and losers was caused by the program, which was created in 2004 and has been a source of controversy ever since.

The study notes that because the sample size of students is fairly small, it can’t rule out the possibility that the program either boosted or hurt college attendance to some degree.

The results are surprising in light of past evidence that the first groups of D.C. voucher participants were more likely to graduate high school and scored higher on reading tests. (A more recent study on the program, focusing on students who participated in later years, found that it caused substantial drops in math test scores.)

Milwaukee voucher recipients more likely to attend — but not necessarily graduate — college

The Milwaukee study offers a more positive story for voucher advocates.

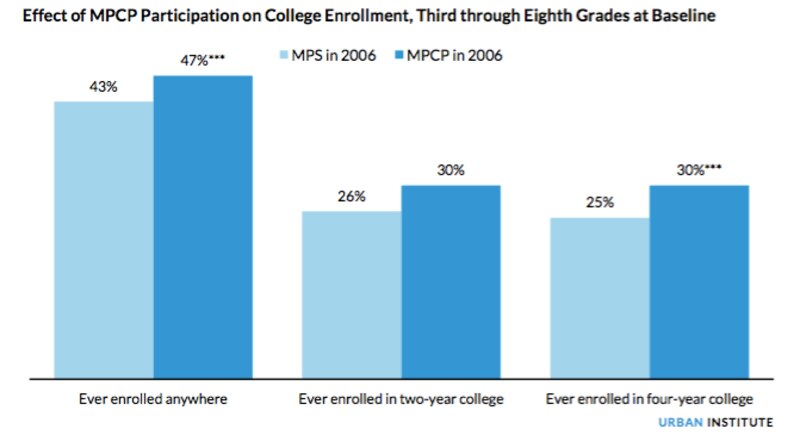

Voucher students were generally more likely to enroll in college, particularly four-year universities, than students with similar test scores from the same neighborhood who were not participating in the program in 2006. For instance, among students who used a voucher in elementary or middle school, 47 percent enrolled in college, compared to 43 percent of similar students.

When it came to actually completing college, though, the results were less clear. The researchers estimated that voucher recipients had a small edge — 1 or 2 percentage points — but the difference was not statistically significant.

In contrast to the D.C. study, the Milwaukee researchers — Patrick Wolf, John Witte, and Brian Kisida — weren’t able to use a random lottery, meaning the results are less definitive. And although the researchers try to make apples-to-apples comparisons, the estimates may be skewed if more motivated families, or students who were struggling in public schools, used a voucher.

The latest results are consistent with a previous Milwaukee study by some of the same researchers. It’s also similar to a recent Florida study suggesting that vouchers led to increases in two-year college enrollment, but had little or no effect on whether students earned a degree.

(Both the Milwaukee and D.C. studies were funded by a number of groups that support school choice, including the Oberndorf Foundation, the Walton Family Foundation, and the Foundation for Excellence in Education. Walton is also a funder of Chalkbeat.)

What we still don’t know

Like the research before it, these studies won’t come close to ending the debate about school vouchers. Opponents will likely highlight the results in D.C. and the inconsistent impact on college completion in Milwaukee. School choice advocates will point to other parts of the Milwaukee study, and the fact that the D.C. voucher programs appeared to keep pace with public schools while spending less per student.

Meanwhile, these studies tell us most about these programs as they existed more than a decade ago. That’s the disadvantage of studies like these of longer-run effects, even as they provide more information about metrics more important to most policymakers and parents than test scores.

“The problem with these long-term studies is that these are the right outcomes to look at, but by the time we know it, it’s of more questionable relevance,” Chingos said.