Families receiving food stamps get their benefits once a month. A few weeks later, kids’ test scores tick up.

The pattern, revealed by a new study of thousands of North Carolina families, suggests that the additional access to healthy food helps students do better in school.

It’s the latest study to quantify how out-of-school factors affect academic performance, and an example of why some districts are embracing “community schools” that try to provide health and other benefits for students and families.

“Improving educational outcomes for low-income children may require looking beyond the school door,” write researchers Anna Gassman-Pines and Laura Bellows, both of Duke University.

The study, published last week in the peer-reviewed American Educational Research Journal, takes advantage of a North Carolina quirk: Food stamps, officially called SNAP, are distributed on different weeks of the month based on recipients’ social security numbers. This creates a natural experiment, since some students’ families will receive their benefits close to the state test, while others will receive them two, three, or four weeks earlier.

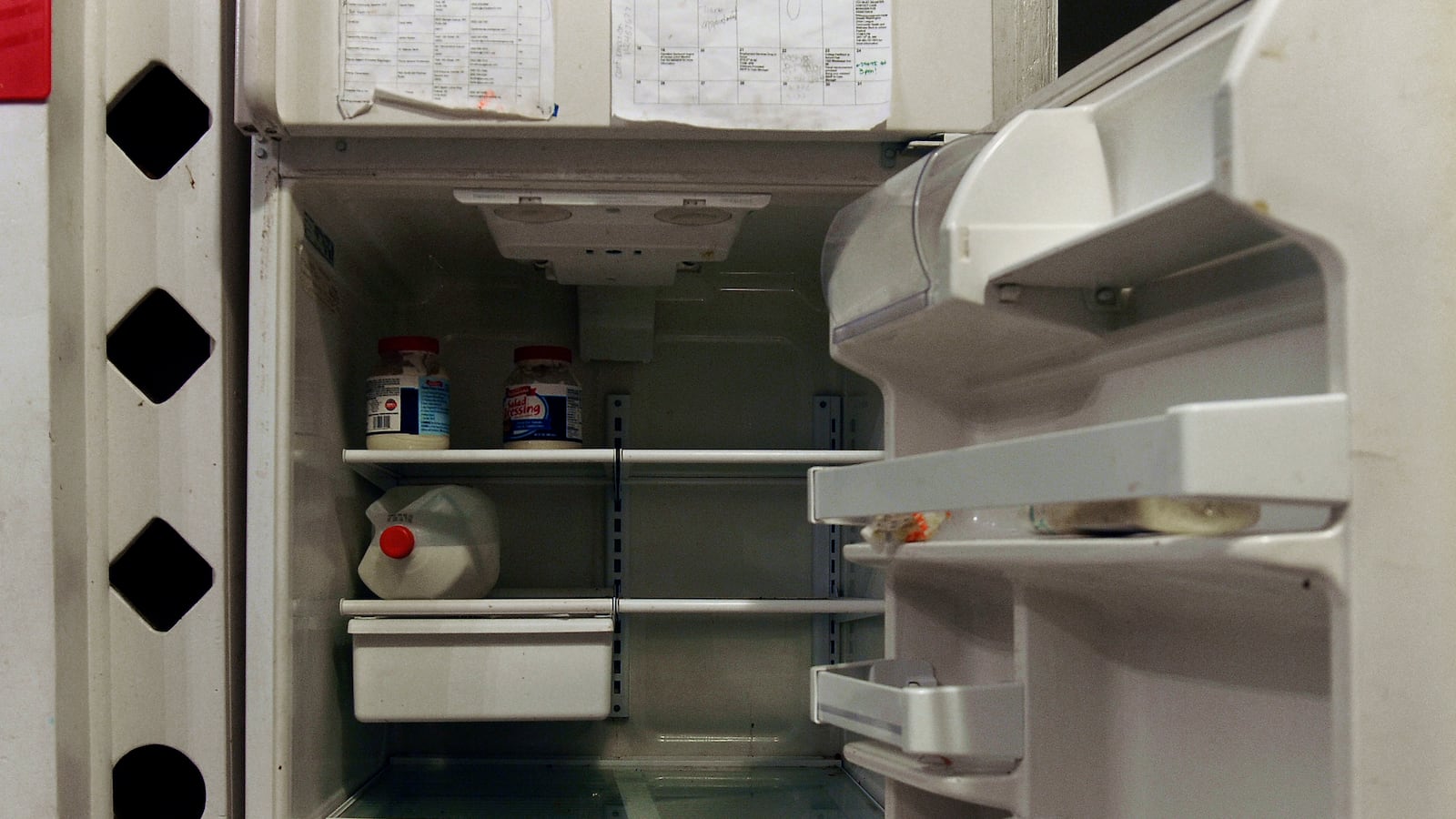

Poor families often run out of money during the month and have to do without or rely on cheaper, less healthy food until their benefits are replenished.

In another study, one person receiving food stamps explained: “At the [beginning of the month] you have all the fun food, you got the meat and the fresh vegetables and stuff and by the [end], you’re eating the breads and the pastas and the canned stuff.”

This idea led the North Carolina researchers to expect student achievement to spike right after the benefits were distributed. But that’s not what they found. In fact, achievement looked like a reverse U — scores were highest around three weeks after families received benefits, and lowest at the beginning and end of that cycle. The differences were modest, but statistically significant.

It’s not fully clear why scores spike around that three-week mark, but the researchers suggest that the academic benefits of better access to food, like improved nutrition and reduced stress, take some time to accrue.

“Students with peak test performance (who received SNAP around two weeks prior to their test date) may have benefited from access to sufficient food resources and lowered stress not only on the day of the test but for the previous two weeks,” Gassman-Pines and Bellows write.

Other research has linked food stamp cycles and what happens in school, too.

A South Carolina study found that students performed worst when tests were administered at the very beginning or the end of food stamp benefit cycles. A paper focusing on Chicago found students receiving SNAP benefits had more behavioral problems at the end of the month, when food may have run low.

In general, participation in food stamp and other government benefit programs have been shown to help students’ academic performance, as well as their short- and long-term health. Research has also shown that healthy school lunches improve achievement.

And while the North Carolina study focuses on how SNAP timing affects students on a specific test day, the researchers point out the consequences going hungry or subsisting on less healthy food may multiply over time.

“[Students] may be less able to learn because of temporarily lowered cognitive functioning or less ability to pay attention,” the researchers write. “Even if these periods represent only a few days each SNAP benefit cycle, these consequences of these ‘lowered learning’ days over the course of the school year may accumulate over the course of the academic year.”