Don’t call schools outdated; call them inadequate. Don’t focus on technology; emphasize the benefits for teachers. And try not to talk about testing too much.

That’s some of the advice advocates of “personalized learning” offer in a recent messaging document meant to help school leaders and others drum up support.

It’s a revealing look at how some backers are trying to sell their approach and define a slippery term — while also trying to nip nascent backlash in the bud.

“We have read the angry op-eds and watched tension-filled board meetings,” authors Karla Phillips and Amy Jenkins write. “In response, we have looked for ways to address the challenge of effectively communicating about personalized learning so it becomes something families demand, not something they fear.”

The document is the latest effort to define “personalized learning,” a nebulous concept with powerful supporters, including Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. (Gates is a funder of Chalkbeat.) Typically, the phrase means using data and technology to try to tailor instruction to individual students, and allowing them to advance to new topics when they’ve mastered previous ones.

But those ideas have begun to encounter opposition from some parents and teachers frustrated with specific digital programs, and from conservative commentators and privacy advocates who worry about technology companies’ access to students’ data.

The messaging document was put together by two groups with a strong interest in maintaining the momentum behind personalized learning: ExcelinEd, the Jeb Bush-founded advocacy group that DeVos used to sit on the board of, and Education Elements, a consulting firm that contracts with districts to help them offer personalized learning programs.

Its suggested rhetoric may become increasingly common. Phillips says she had presented these ideas to the National Governors Association and the Council of Chief State Schools Officers.

“We want to pave the pathway for districts to move forward faster and easier and with greater support,” the report says says.

What not to say

The analysis, based on polls and focus groups, lists a bevy of ideas that advocates should generally avoid or at least approach cautiously.

They shouldn’t talk about standardized testing, or even “more innocuous-sounding statements such as, ‘student mastery will be determined through frequent assessments.’” They shouldn’t use the phrase “student agency, voice, and choice,” which “can send the message that students can do what they want.”

Another thing to steer clear of: talking up the potential for dramatic changes to the way school looks and feels.

“In attempting to generate excitement, we inadvertently scared the public,” the report says.

That also means not discussing specific changes — like new bell schedules or grading systems — that schools might see as a result of adopting a personalized learning approach.

“Even though some of the potentially big changes … may be true, experience tells us that very few of these changes will occur in the first few years of implementation,” the report says. “For that reason, there is little reason to raise hackles in the earliest phases of discussion.”

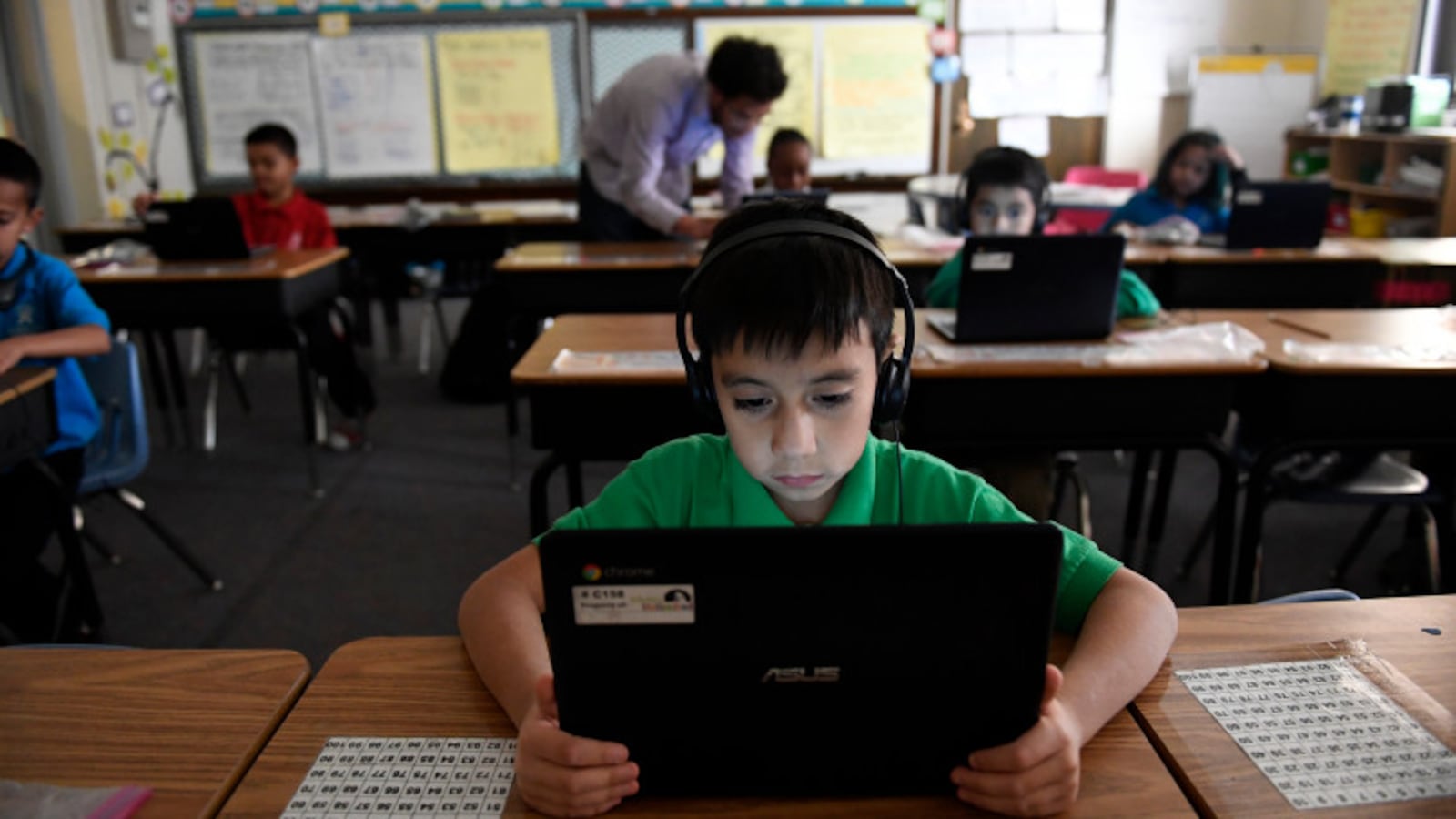

And then there’s technology. Many of the most visible examples of personalized learning are computer programs that help students learn new concepts and track their progress in some way. That connection can be a problem, the report acknowledges, since advocates want personalized learning to be seen as a broader philosophy.

“There is indeed great risk of these misunderstandings developing if personalized learning is perceived to be predominantly digital, especially when families add their concerns about screen time and what students will be able to access online,” the report says.

Instead, personalized learning evangelists should tell families that “their children are unique and special”; rely on teachers as the “best messengers”; and emphasize purported benefits for students, like working at a flexible pace, and for teachers, like new tools to monitor students’ learning.

“Rhetorically, it’s fascinating,” said Doug Levin, a longtime observer of education technology who used to head the State Education Technology Directors Association. “You have a movement in many respects which is predicated on technology to collect information about student learning, if not then to also deliver instruction. That … movement then is trying to, in some respects, forsake its roots to convince people to go down that path.”

It’s not just EdElements and ExcelinED. The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative is also trying to expand the definition of personalized learning by including its efforts to offer eyeglasses to students who need them, for example. Other CZI education efforts have focused on technology, like the Summit learning platform, an online program that CZI says helps students “learn at their own pace,” and a partnership with MIT and Harvard to create an online tool intended to promote literacy in early grades.

In an interview, Karla Phillips, one of the authors of the report, said she didn’t want to define the concept too narrowly or even point to specific models.

“If you look at the pilot [programs] we’re working with, this is going to look dramatically different” from place to place, she said.

Assumed benefits, but limited research

The report operates under the assumption that personalized learning approaches are successful, in high demand, and here to stay. “This is something most families want,” it says. “It is not, in fact, ‘another reform.’”

But these remain relatively open questions. For instance, the report suggests telling parents that “personalized learning provides opportunities for increased interaction with teachers and peers and encourages higher levels of student engagement.”

If anything, though, existing research suggests that certain personalized learning programs reduce student engagement. In a 2015 study by RAND, commissioned by the Gates Foundation, students in schools that have embraced technology-based personalized learning were somewhat less likely to say they felt engaged in and enjoyed school work. A 2017 RAND study found that students were 9 percentage points less likely to say there was an adult at school who knew them well.

Rigorous research on the academic benefits also don’t offer definitive answers. Some studies have shown real gains, particularly for math-focused technology tutoring programs; a few others have shown no effects; and many programs and schools have never been carefully studied.

Phillips of ExcelinEd says that the RAND work is the top research in the field. That latest study found that schools that adopted technology-based personalized learning approaches, with the support of the Gates Foundation, had modest positive effects on test scores. The average student moved up roughly 3 percentile points in math and reading, though the reading impact was not statistically significant.

Philips says these findings should lead to optimism, but suggests there are limitations to studying such an all-encompassing idea.

“I do feel strongly it shouldn’t be an ‘it’ or a thing — it’s not a curriculum, it’s not a textbook that you buy,” she said. “It’s about broadening schools’ ability to meet the needs of students.”