Charity, a Boston mother, had a number of schools in mind for her young daughter. But there was a problem: by the time she registered for the city’s admissions system, the spots in every one of them were taken.

The school she ended up with, she said, was “just a huge headache because it doesn’t coincide with my time. I’m late for work every day.” When she complained to district officials, she said, “It was like, ‘There’s nothing that we can do.’”

Because her daughter had recently moved from out of state, Charity started the registration process in the summer, several months after the deadline for the first round of admissions.

Her story is not a one-off, according to new research.

It finds that early registration deadlines for Boston’s school choice program tended to trip up black, Hispanic, and low-income families. That’s in part because they move more frequently; that in turn means they apply later and get less of a chance to pick from the most coveted and high-achieving district schools.

The result ends up undermining one goal of these choice systems, which have been promoted across the country as a way to ensure disadvantaged students aren’t trapped in struggling schools.

“The families who may stand to benefit most from school choice also likely experience the greatest challenges in taking full advantage of it,” conclude study authors Kelley Fong of Harvard and Sarah Faude of Northeastern University.

The research, published last week in the peer-reviewed journal Sociology of Education, focuses on Boston Public Schools, which has an extensive system of school choice. Families rank their preferences, and an algorithm assigns students to schools. There are no default neighborhood schools, so all students who want seats in district schools must participate. (Most charter schools are not included.)

Ideally, families looking for a seat at a school in the fall register in January, allowing them to participate in the choice system’s first round. Those students get the initial shot at the city’s most popular schools.

The school system then runs a second, third, and fourth round of that system. Students who register in the summer, after the process is formally complete, get assigned last based on what schools have seats available.

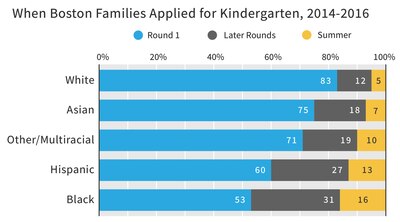

For kindergarteners, less than two-thirds of families go through the first round, and 12 percent register in the summer, the study finds, using data from 2014 to 2016. But those numbers vary substantially by student group.

Eighty-three percent of white students went through round one, compared to just 60 percent of Hispanic students and 53 percent of black students. Similar disparities existed between students coming from wealthier and poorer neighborhoods.

Those gaps mean that some students miss their shot at schools that are highly rated or in demand. Of 72 schools offering general education kindergarten, 50 were filled up after the first round in the most recent school year. Those also tended to be higher-achieving schools.

“Of the schools without waitlists by the summer-time, none were in the top test score quartile of district schools,” according to the study.

Why do families participate in the choice system late? To find out, researchers surveyed well over 1,000 late-registering families and interviewed about 30 of them. (An important caveat: those who responded to the survey and an interview request may not be representative of all families who registered late.)

In the survey, most said they were late because of a recent move into the city, making it difficult or impossible to meet the registration deadline.

A notable share of families in this study also said they weren’t aware of the registration gap or didn’t know it mattered; were counting on or considering alternatives to the district schools; or simply had too much going on. A small share — around 5 percent of families — said it was because they didn’t feel strongly about choosing a school.

There’s also some evidence that the multiple systems of enrollment among the city’s district and charter schools lead to confusion. (Although a number of districts have a common enrollment system, Boston doesn’t, despite a recent effort to put one in place.)

One parent described applying for a charter school lottery early because she understood that there were hard deadlines for entering a charter school. But she didn’t apply to the district schools until after the first round had ended, thinking one she wanted would be available when she needed it.

“Parents often oriented their choice efforts around other school timelines, looking to BPS only later when other options were unavailable or no longer desired,” the researchers write. “Unfortunately, by then, the BPS schools they wanted often had no seats remaining.”

This research can’t quantify what these disparities mean for student learning. But another recent study found the type of students who stood to gain the most from Boston’s high-performing charter schools were also the least likely to enroll. (Interestingly, the same phenomenon has been observed in the Head Start pre-kindergarten program.)

Other cities have tried to deal with this enrollment problem. After a 2013 report showed that late-registering students were being concentrated in struggling New York City high schools, district officials set aside additional seats in other schools. In Denver, the district has taken similar approach and recently increased the number of seats it holds for late-arriving students.

“The Boston Public Schools appreciates the research on this important topic, as we have made some shifts to support increased outreach to our most marginalized families,” a spokesperson for the district said in a statement. “We are carefully evaluating the study’s findings to determine if there are additional ways we can improve our registration process to make it more accessible to families.”

The researchers said they worked closely with Boston Public Schools administrators, who first raised the concern about late registrants to the study’s authors and provided data to make the analysis possible. Since 2016, the district has made some modest steps to improve the process, like creating “pop-up” registration centers in neighborhoods with high rates of late entry.

But the study notes one reason the school system might be discouraged from changing its system: Boston advertises that 77 percent of kindergarteners who go through the first application round get one of their first three school choices.

“Late registrant families registering earlier in substantial numbers would compromise this high ‘success’ rate,” the research says.