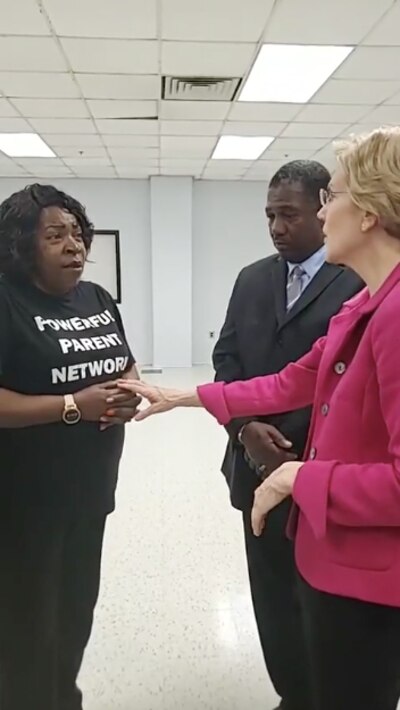

Elizabeth Warren defended her education plan — while also promising to go back and read it — in a meeting with pro-charter activists Thursday, a lengthy video of the conversation shows.

The Democratic presidential candidate argued that her plan seeks only to put charter schools on an even playing field with district schools.

“Nothing in my plan says we’re going to close any existing charter schools,” she told the activists, including longtime school choice supporter Howard Fuller and Sarah Carpenter of the Memphis Lift. “Nothing says that we’re going to end charter schools if they’re meeting the same standards.”

And while Warren did not make specific promises, she appeared to leave some room for change. “If I don’t have the pieces right, I’m going to go back and read it,” she said of her plan. “I’m going to make sure I got it right.”

Saloni Sharma, a spokesperson for the campaign, reiterated Warren’s perspective: “In the meeting, Elizabeth noted that charter schools should have to meet the same standards as public schools — as her plan says. She noted that funding for existing non-profit charter schools is not affected like her plan says. She believes that we should not put public dollars behind a further expansion of charters until they are subject to the same accountability requirements as public schools — like her plan says.”

Warren’s education plan, which she released last month, proposes limiting charter schools in a number of ways. It promises to ban for-profit charter schools and eliminate federal funding for new charters. Warren’s plan also seeks to limit who could authorize charters — the kind of change that could threaten existing schools, though one that it’s unclear whether a president could pull off. It’s a reflection of a growing skepticism about charter schools among Democrats, though two recent polls show black and Hispanic Democrats tend to be more supportive.

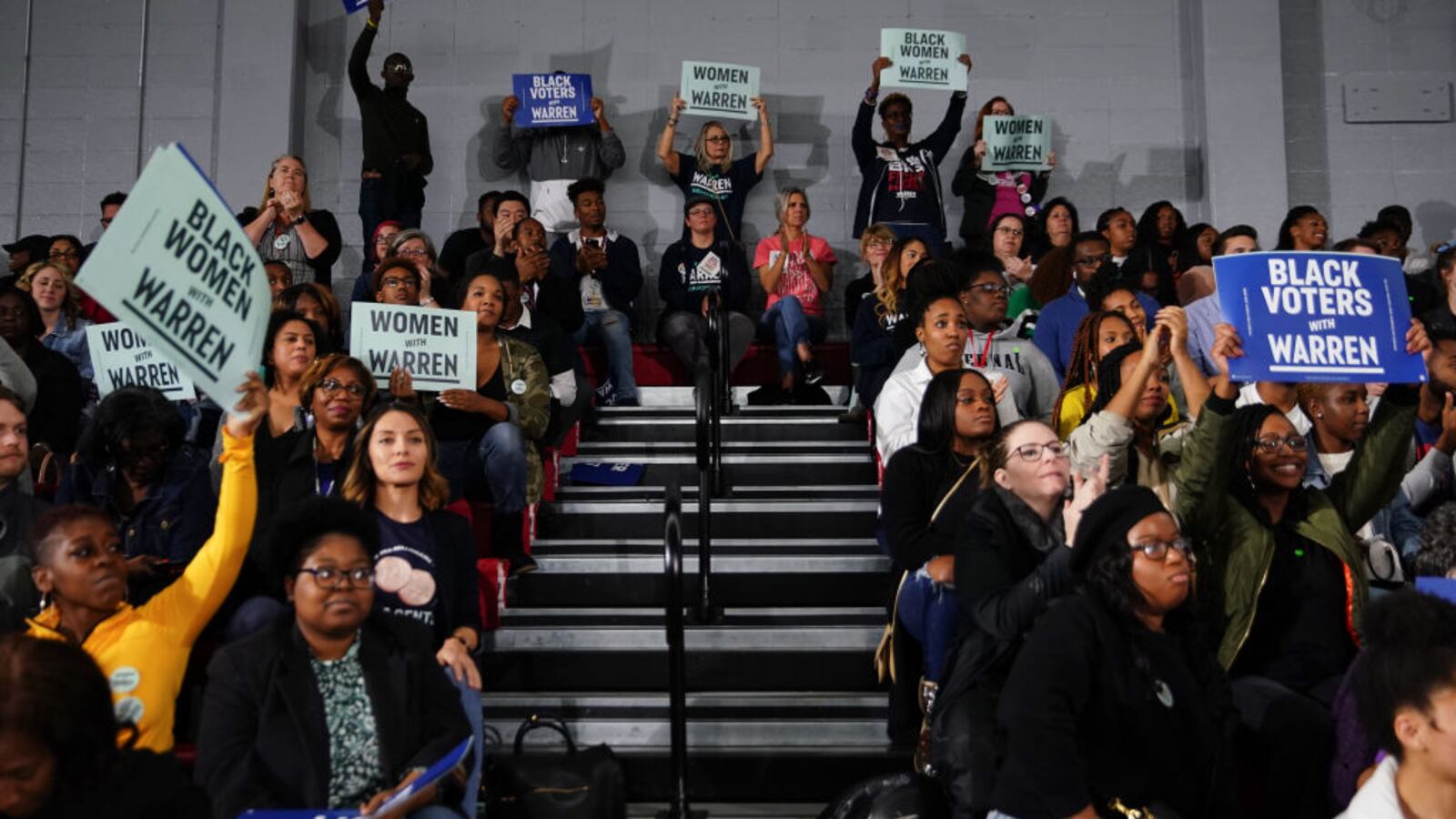

The meeting followed a Warren campaign event in Atlanta, where the Massachusetts senator gave a speech focused on black activism. The group of parent activists disrupted that speech with chants of “our children, our choice.”

Fuller said Rev. Miniard Culpepper, a Boston pastor who is close to Warren, came over and offered a meeting with Warren if they stopped. They agreed.

“To her credit, she came down to meet with us,” Fuller told Chalkbeat. “We were there to support good schools and the power of parents to choose.”

In that meeting, Fuller, former Milwaukee schools chief and advocate for private school vouchers, told Warren that her language is helping anti-charter efforts across the country. A number of states, including California, Illinois, and Michigan, have recently moved to limit charter schools or cut their funding.

“Your plan starts out with an attack on charter schools,” he tells Warren.

“What you may see as an attack is designed to say everybody’s got to meet the same standards,” Warren counters.

Throughout, the activists say they support the idea of charters meeting the “same standards,” though it’s not clear exactly what either party is referring to. (Depending on where they are located and who they are authorized by, charter schools are often exempt from rules that apply to public school around things like public records and teacher certification, and are held accountable for academic performance in different ways. Opponents say that’s a problem; supporters argue that charters are held to performance contracts that amount to a higher standard.)

In the conversation with Warren, Carpenter emphasized her personal experience. “Charter schools saved my grandbaby because every school in my community was failing,” she said.

At one point, Carpenter said that she had heard that Warren sent her own children to private school, perhaps alluding to a recent article in the New York Post. Warren responded, “No, my children went to public schools.”

Asked to clarify, a campaign aide said, “Elizabeth’s daughter went to public school. Her son went to public school until 5th grade.”

This appears to align with the Post article, which found evidence that Warren’s son attended a Texas private school in 5th grade.

Warren said she wants to increase funding for public schools, by quadrupling Title I dollars for schools serving low-income students and providing more federal money for students with disabilities. Fuller was not persuaded.

“If you don’t say there has to be significant structural changes in order to use that money — that money is going to go down the drain,” he told her.

Warren did not agree. “I have to say, I don’t think that’s true in every school. Why would you say that’s true everywhere?” she responded. (Research has found that public schools generally do improve when given additional resources.)

The discussion ended with a prayer, led by Culpepper as the group held hands. Warren hugged Carpenter and said she appreciated her comments.

Fuller told Chalkbeat that roughly 200 people from a number of overlapping groups took part in the protest. That included the Freedom Coalition for Charter Schools, a group that Fuller started with Connecticut charter school leader Steve Perry. They worked with the Powerful Parent Network — a collection of groups in Atlanta, Nashville, Memphis, and elsewhere — to mount protests outside the Democratic debate in Atlanta and then attend Warren’s rally.

They were funded by an online campaign, which has raised over $16,000 from a mix of small donations and several anonymous $1,000 contributions.

Fuller said his group hasn’t received any direct financial support. A number of groups present have been backed by pro-charter philanthropies and wealthy funders, though.

Carpenter’s group, the Memphis Lift, has received $1.5 million from the Walton Family Foundation since 2015. Carpenter told ABC News that the trip was not funded by Walton, which was singled out for criticism in Warren’s education plan.

Lakisha Young said most of the staff of the Oakland Reach, a parent group, was in Atlanta for the protest. The Oakland Reach is funded by local and national foundations, including Walton and The City Fund, which is backed John Arnold and Reed Hastings. (Arnold and Walton are also Chalkbeat donors.) Bryan Morton, who leads a Camden group supported by The City Fund, was also present.

Young said she’s happy to talk about her group’s donors, but that the focus should be on what is driving parents’ activism.

“As interested as people are in our funding — totally get it — but we would love people to also be interested in why we get up every day and do this work,” she said.

Fuller said critics who focus on funding are using a long-standing tactic to discredit black activists. “I don’t give a damn what they say about where the funding came from — it’s an old trick that they’re using,” he said.

Fuller says he will keep trying to engage the Democratic candidates. He said has spoken with an advisor to Pete Buttigieg’s campaign and directly to Cory Booker, who reiterated his support for charter schools in a New York Times op-ed earlier this week. And Fuller’s group, the Freedom Coalition, will be in Los Angeles in December for the next Democratic debate, he said.

“We are not going to go away,” he said.