When teachers in Los Angeles went on strike last month, their leaders warned that they would be off the job for “as long as it takes” to reach a deal with the district.

They were back in class after six school days.

That timeline could offer a template for what happens in Denver as teachers there strike over how the district pays them. The recent wave of teacher activism has resulted in several major strikes and work stoppages across the U.S. in the last 18 months — all of which have resolved within two weeks, and usually in not much more than one.

Chicago’s 2012 teacher strike, which like Denver’s reflected resistance against a certain brand of education policy as much as a bid for improved compensation, lasted seven school days. In 2015, Seattle teachers started the school year by striking for five days.

Last year, statewide teacher actions caused some schools to close in Oklahoma and West Virginia for nine days and Arizona for five days. Teachers in Pueblo, Colorado, also held a five-day strike last year.

Influencing the pattern are the needs of parents, students, and teachers themselves.

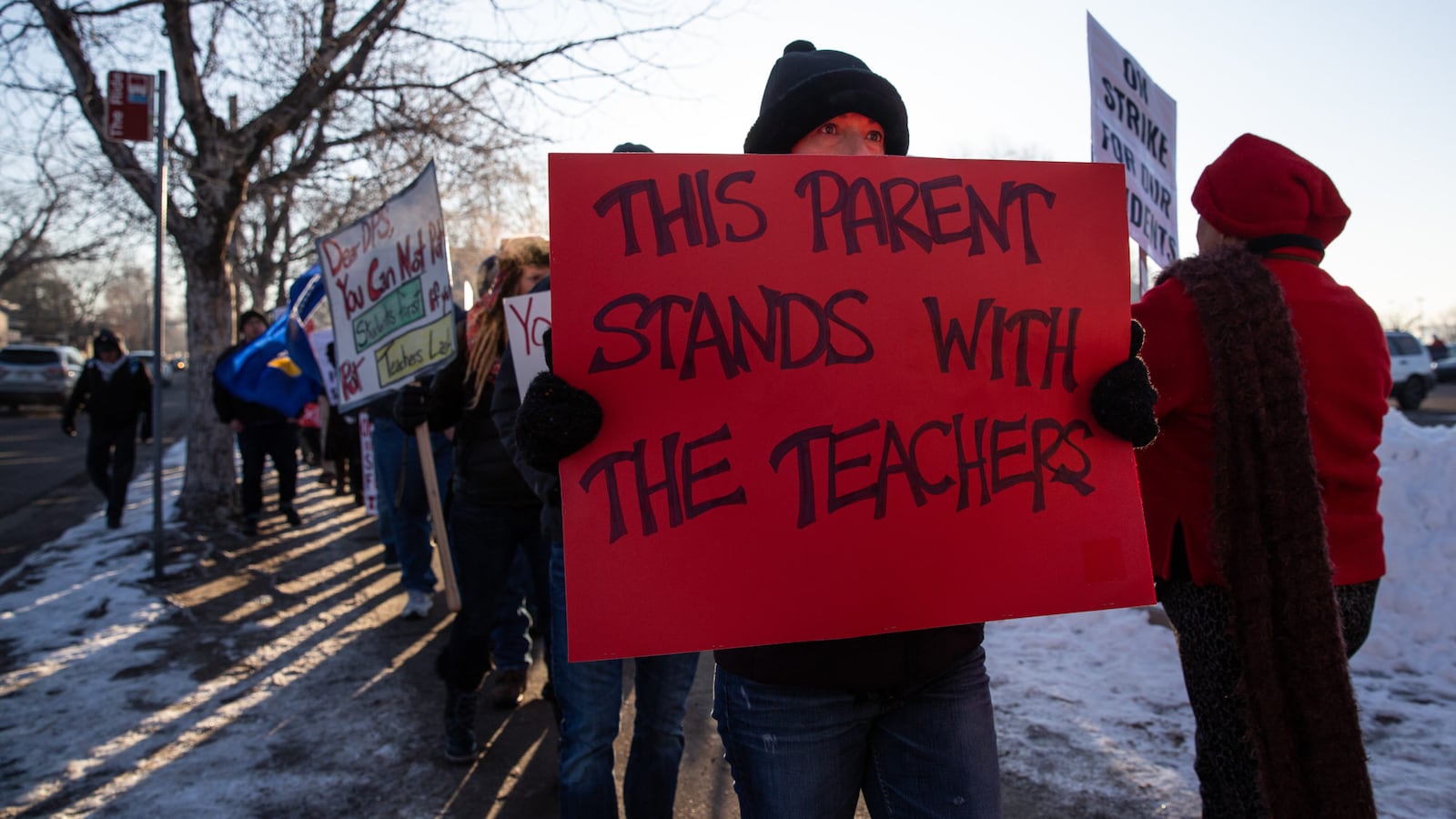

Striking teachers tend to enjoy significant support from their local communities, but families can tolerate only so much disruption before growing weary. In districts like Denver and Los Angeles where many families are working-class, staying home to care for students who are out of school can quickly jeopardize families’ savings and even employment.

“Two weeks of a strike are on the outside of what we can expect parents to support, both in their own interests … and their kids’ interests in learning,” said Katharine Strunk, a professor at Michigan State University who studies teachers unions. “Think about having five days or nine days out of the classroom for strikes. It’s not good for kids.”

Teachers also have a strong incentive to get back to work: They don’t get paid for days that they strike, a tough position to sustain for workers so distressed about their compensation that they are willing to take collective action. More than 400 people have contributed more than $25,000 to a union fund to support Denver’s striking teachers, but that can hardly cover the salaries of the thousands of educators expected to strike.

“It may well be that going a month without pay just isn’t feasible for people who just had their savings come back” after the financial recession, Strunk said.

Teacher strikes haven’t always followed the same timetable. In the late-1960s and early 1970s, schools in several cities were closed for weeks at a time as teachers pressed their districts for increased funding and better work conditions.

New York City schools, for example, shut for 36 days scattered over three months in the fall of 1968, and Philadelphia schools closed for 11 weeks during the 1972-73 school year — including an eight-week stretch in late winter that included jail time for union leaders who ignored a court order to send their members back to work.

For the most part, strikes since that era have taken place as part of a broader pattern, and most have been shorter. (A notable exception can be found in Chicago, where the union struck five times during the 1980s, including for a 19-day stretch in 1987.)

Several specific features of the teacher strike in Denver could influence its length. For one, Denver’s union is negotiating only over how teachers are paid, and negotiations have narrowed the scope of the disagreements significantly already. In contrast, it took union and district negotiators more than a week to work through dozens of disagreements on a wide range of topics.

The Denver district’s approach to operating schools during the strike could also play a role. In Los Angeles, while most schools remained open, parents were encouraged to find alternate child care and the vast majority of children did not attend. In Denver, both the district and union have encouraged families to continue to send their children to school. If students do go to school in large numbers, families could face less need to jerry-rig child care arrangements — potentially sustaining the strike’s public goodwill. On the other hand, if students experience chaotic conditions inside their schools, pressure for the strike to end could grow.

One more clue to the strike’s ultimate length could appear in Denver’s existing school calendar. Los Angeles’s teachers union started its strike on a Monday, then returned to the bargaining table during a scheduled day off, Martin Luther King Day, and reached a deal with their district the following day. Students were back in class on Wednesday.

A similar turning point is already built into Denver’s school calendar. The strike is starting on a Monday. Next Monday, Feb. 18, is Presidents Day — already a planned day off for students and teachers.