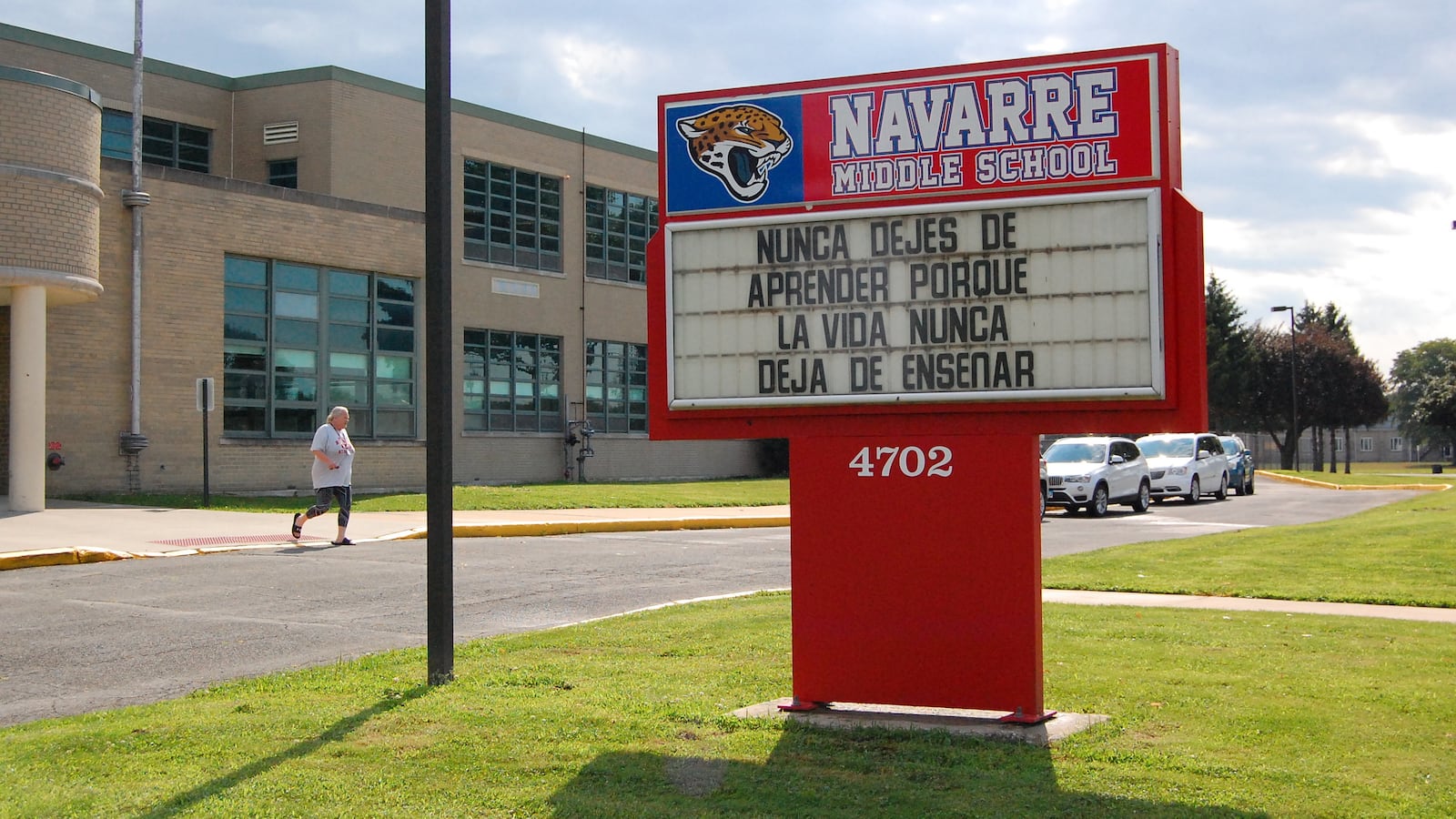

SOUTH BEND, Ind. — Principal Lisa Richardson knows it will take a lot to turn around Navarre Middle School.

Two years ago, a state review laid bare the many issues plaguing the school. Administrators had low expectations for students and staff. Teachers received little feedback. Suspension rates were high. The school, which enrolls Latino students and English learners at twice the rate of the South Bend district, isolated English learners and used untrained, uncertified staffers to serve them. Parents reported communication with the school was poor. One staffer summed it up this way: “We need help!”

Now Richardson, newly hired from another Indiana district, is trying everything she can to lift the school’s academic standing. She hopes to grab students’ attention with new dance and theater electives and more exposure to engineering. She plans to make the building more inviting with cooking classes for parents and murals by local high school artists. And she’s hired a new crop of teachers to fill critical staffing gaps.

“Here at Navarre, our tagline is ‘Take another look,’” she said on a recent school tour.

As she makes those changes, Richardson has tools that other South Bend principals don’t — the ability to pay her teachers to attend extra training and to opt out of the district’s reading and math programs in favor of her own choices.

Her new powers stem from an arrangement known as an “empowerment zone.” South Bend officials agreed to let Navarre and its four feeder elementary schools operate independently from the school district for five years, reporting to their own board — a shift big enough to prevent the state from taking over or shuttering Navarre after it received its sixth straight “F” grade from the state.

Some see the strategy as a more collaborative middle ground than a typical state takeover. Others, including some teachers unions, see a takeover in disguise, and say proponents downplay the importance of the elected board’s loss of control.

“Is this really a choice?” said Domingo Morel, an assistant professor of political science at Rutgers University, Newark who wrote a book about state takeovers of local school districts. “There’s just a lot of concerns that come along with that absence of public accountability.”

A few early but encouraging academic results, though, plus enthusiasm from education philanthropists, have fueled the strategy’s spread. South Bend is modeling its changes on a similar empowerment zone in Springfield, Massachusetts. And like several other districts, South Bend is turning to Empower Schools, the organization that designed the Springfield playbook, to help them do it.

“When people go to see transformation zones and … the work that Empower is doing, we don’t want them to go to Springfield, we want them to come here,” said Todd Cummings, South Bend’s recently promoted schools superintendent.

So far, Empower has helped start 10 empowerment zones in five states, though not all of them are aimed at improving struggling schools. Five are new this school year, including ones in South Bend, St. Louis, and Lubbock, Texas.

And Empower Schools could be working in more cities soon. Co-founder Chris Gabrieli says the organization is exploring four more zones in Texas. (Gabrieli is also a Chalkbeat supporter.) And a spokesperson for the Rhode Island education commissioner said Empower Schools had “reached out to offer more information about their work and how it may be helpful in Providence,” where the state is about to take over the city’s schools. Gabrieli said Empower had provided that information upon request.

How this works — and how it’s spreading

The changes coming to South Bend are part of a larger movement to offer schools some of the powers that district central offices have traditionally held — the kind of autonomy usually granted to charter schools. Sometimes the efforts are branded as “innovation” or “partnership” zones. Often, they involve bringing in charter school operators to run district schools. Sometimes they weaken the local teachers union. In Indianapolis, for example, innovation school teachers aren’t covered by the local union contract.

In Springfield, the elected school board and the teachers union agreed to the changes. In 2015, a nonprofit board was appointed to oversee the zone schools. One charter school did step in to manage a struggling middle school, though there’s been no other charter involvement. Teachers in the zone, who work more hours for higher pay than other district teachers, have their own union contract.

Several school districts have sent officials to visit Springfield to learn about the model, including South Bend and St. Louis.

“Many people in the ed reform movement act as if the only people who want to help change and improve the opportunities for kids are outsiders,” said Gabrieli, who chairs the Springfield zone board. While there’s room to bring in new talent, he says, “mostly the people making all the good stuff happen” in Empower’s zones are local teachers and civic leaders.

The work is being fueled by national and local philanthropies, as well as states, local districts, and nonprofit boards that run zone schools. In recent years, the Dell and Walton foundations together have given Empower Schools more than $2 million. (The Walton foundation also supports Chalkbeat.) And in Texas, where Empower is one of seven organizations pre-approved to set up a “transformation zone” with low-performing schools, the state education agency invests heavily in these initiatives. Waco, for example, has used almost $500,000 in state money to pay for Empower’s help with its zone.

Beth Schueler, a University of Virginia assistant professor of education who studied the Springfield effort, says this model addresses common criticisms of school boards — sometimes seen as dysfunctional and dominated by special interests — and state takeovers, which have led to academic gains in some places but are often politically difficult and disempowering, especially in the majority-black school districts where they are most likely to occur.

“We don’t have a lot of bright spots and positive stories that we can look to as models to apply in other places,” Schueler said. “Because there are so few models out there, I think it makes sense that people want to try this.”

How much of a choice is this?

Gabrieli says that local districts choose to work with Empower Schools. But districts often find their model when a state intervention is looming.

In Waco and Lubbock, Texas — home to two of Empower Schools’ zones — the local school districts were faced with closing schools, allowing a state takeover, or creating a zone. In Springfield, Massachusetts, the district had also faced a state takeover, and in St. Louis, the district has been under pressure to raise student performance to avoid going back into state receivership.

“When you create this type of crisis, this type of urgency and then you provide these options, what is a community to do?” said Morel, the Rutgers-Newark professor. “You’re going to try to pick the least disruptive, the least problematic option. But does it mean that it’s good?”

He says some of the same concerns raised by state takeovers apply here. First, it’s unclear how accountable the appointed nonprofit board will be to the community. Second, when you break up a larger school district into smaller groups of schools, it can make it harder for communities to organize. Morel questions whether this is another “shortcut to address major challenges,” like inequitable school funding.

The local union in Springfield has also soured on the changes. Maureen Colgan Posner, who heads the teachers union in Springfield, says the union was initially swayed by the threat of a state takeover. Now, though, she’s concerned that the “stripped down” contract that zone teachers have doesn’t do enough to protect teachers’ time, and about the impact of the loss of an elected board. (Though teachers did “overwhelmingly” approve the new zone contract last year, she said, largely because it included salary increases to compensate them for additional work time.)

Colgan Posner has since testified against legislation that would expand empowerment zones in Massachusetts, and questions whether it should be held up as a national model.

“You don’t need an empowerment zone to have collaboration,” she said. “They’re selling this, but we don’t have any proof that it’s absolutely the solution.”

Another challenge Empower faces is wariness from officials in places that have experienced a slew of unsuccessful reforms. That’s been the case in St. Louis, which is launching an empowerment zone with two of the lowest-performing schools in the district.

The district itself was only returned to local control last month after 12 years of state management. Though the elected board supports the plan now, members initially raised concerns that it could again take power away from schools.

“The pushback from the elected board is coming from a place of distrust, given the history of what has happened here in St. Louis,” said Priscilla Dowden-White, an associate professor of history at the University of Missouri-St. Louis who was chosen to lead the nonprofit board. “They’re not being paranoid. There’s some good reason for that distrust.”

Do these changes help students learn?

There is some evidence that the strategies used by Empower’s go-to districts have led to academic improvements, especially in cases where the schools added learning time for students. While this is a common feature of other turnaround strategies, a zone structure can make it easier to have teachers work longer hours for extra pay.

Schueler and two other researchers found that interventions in Lawrence, Massachusetts — where Empower’s co-founders were involved in a state takeover of schools before starting their organization — led to sizable gains for students in math and modest gains in reading, compared with similar school districts in Massachusetts. Lawrence students who received intensive tutoring with teachers over their vacation breaks saw especially large gains in math. In a separate study, Schueler found that students in Springfield who attended similar “vacation academies” also made notable gains in math.

There haven’t been rigorous studies elsewhere, and early results on state tests have been mixed. A state progress report on the first two years of the Springfield empowerment zone showed students were growing faster in reading, but not in math. One year in, some schools in Waco, Texas’ zone saw their scores improve in math and reading, but others saw them drop.

Schueler cautions that it’s difficult to say if the gains will be long-lasting, and if they can be repeated in districts with different student demographics and state policies. Springfield and Lawrence are both mid-size, majority-Latino districts with a high proportion of English learners, and both are also located in Massachusetts, which spends more on education than most states. And not all of the zones will use their flexibility to make the same changes.

In South Bend, the zone is now up and running. It’s led by Cheryl Camacho, who was recruited by an Empower-recommended search firm. Camacho, a former teacher and principal, moved to South Bend after getting her doctorate in education from Harvard. She’s enrolling her own two children in a zone school.

What happens next will largely depend on what South Bend officials decide to do with their new powers. This year, teachers and principals will have to decide whether to change their school calendar and, if so, what to do with the extra time. Camacho also has to decide how, exactly, she will hold schools accountable for improving, and how to show school communities that she’s serious about giving them more support than they’ve had in the past.

“It’s easy to look at a community and say parents don’t care, they’re not showing up,” she said. “But that comes from experience. We have to prove that we’re doing right by their children in order for them to trust us.”

This story has been updated with additional information about the Springfield union’s vote.