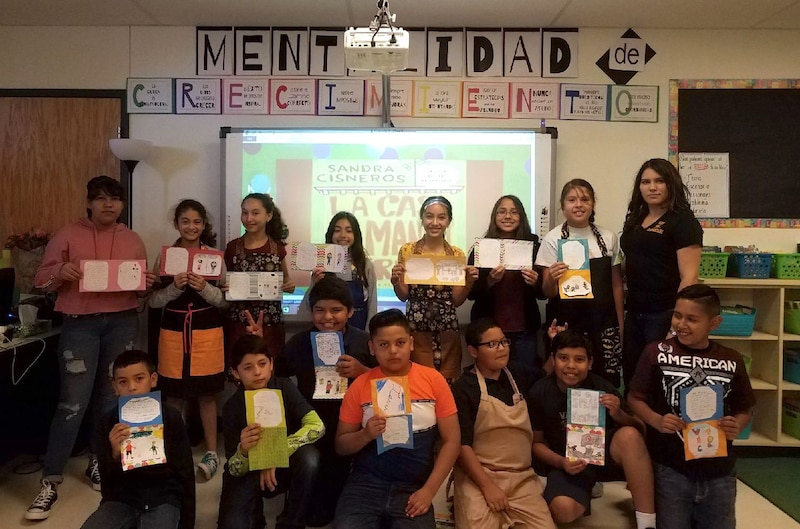

As part of a recent social studies lesson, Lourdes Sierra’s sixth-graders spent time reading about Chicago. Their task was to make connections and comparisons between the bustling city 1,500 miles away and their small New Mexico community, where students identified a handful of businesses: two dollar stores, a restaurant, and three gas stations.

“Even though we’re a small community, I think we help each other,” Sierra said. “We do have a lot of people moving in and out, because of different jobs that they have, but when something happens, we all come together.”

Sierra teaches at Vado Elementary School in Gadsden Independent School District, where nearly every student is from a low-income family. Her school is located about halfway between Las Cruces, New Mexico and El Paso, Texas.

Sierra is going into her sixth year as a bilingual teacher at Vado. After teaching kindergarten for several years, she’s now taking on sixth grade and working to become a bilingual education administrator.

There’s a big need for that in her district, where more than a third of students are English learners — one of the highest rates in the state. Sierra also sits on a district committee working to expand dual language programs, so students from her school will eventually learn all their academic subjects in English and Spanish from pre-kindergarten to 12th grade.

“It is a challenge, but at the end it is very rewarding to see all the students learning and reading and writing in both languages,” she said.

We talked with Sierra about how she bonds with her students, how she makes reading more exciting, and how the recent uptick in immigration enforcement has affected her school. The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Was there a moment when you decided to become a teacher?

I was born here in the U.S., however, I was raised in Mexico. I lived in Mexico for 15 years and I then I came back as a sophomore in high school. It was really hard for me to be in the ESL classes and all the classes I needed to graduate. It was a shock for me, not only the language, but the culture and all of that. That was my thinking when I decided to go to university, that I wanted to become a bilingual teacher. I wanted to support those students; I didn’t want them to go through what I went through.

How do you get to know your students?

At the beginning of the school year, I asked them to write a letter for me, letting me know like: ‘Ms. Sierra, I like this, I don’t like this, I need this.’ I [said to] them: This is your time to ask me for anything you want, any help you need. I was surprised — some of them were really honest, telling me, for example: ‘Please, Ms. Sierra, I need help with math because I’m not good with multiplication.’ Especially for this age, it has been powerful for me.

Tell us about a favorite lesson to teach. Where did the idea come from?

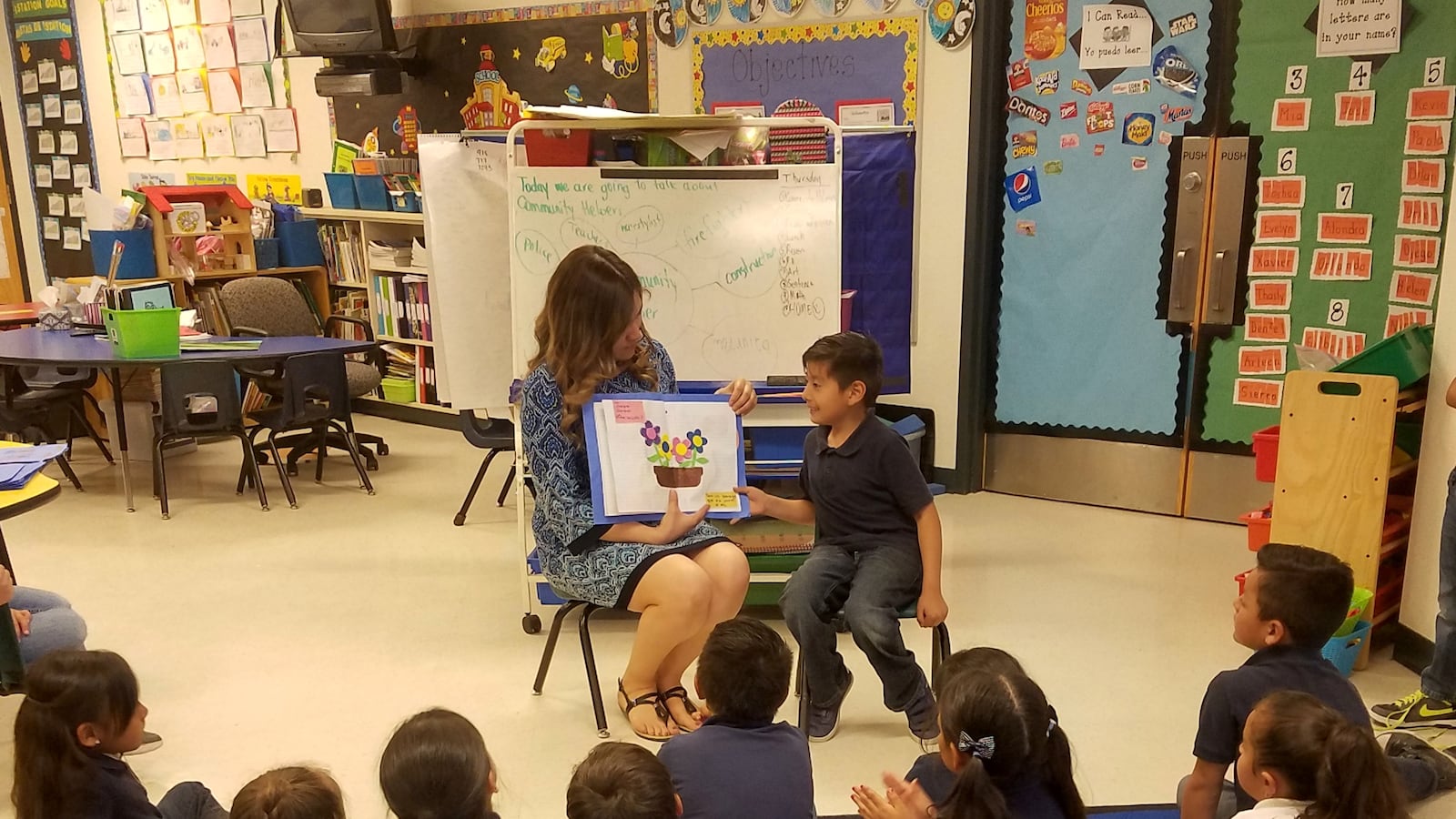

One of the things that I see, and it is across grade levels, is students have a hard time with reading. Many times they don’t enjoy reading. In kindergarten, we did a reading challenge. For example, one day they were supposed to read with a friend. Another day, they were supposed to read at the park, or maybe in the car or under the table. They were able to choose anything they wanted for that specific day. And then I also asked parents to take pictures of them, and we displayed the pictures outside our classroom and we said: ‘Todos somos lectores,’ ‘Everyone is a reader.’ I want them to look at reading like something that they enjoy, not like, ‘Oh, I have to read again.’

What’s something happening in the community that affects what goes on inside your classroom?

Many of our parents, they didn’t have the opportunity to go to school. Last year in kindergarten, many of the students, it was their [parents’] first child in school, so they were having a hard time understanding, why is it that I need to do this or that. We try to make them feel welcome, and make them feel like even though I’m the teacher in here, I’m still going to learn from you.

We have immigration issues. There was a time when many students were not coming to school because there were the redadas [immigration raids]. They were afraid, and they were not coming to school, and it was an issue for us. I remember clearly, they told me this little girl can go to the front office, she’s going home. And she didn’t want to go; she was afraid it was going to be officers or somebody like that. I’m like, ‘OK, I’m going to go check, and then I’m going to ask your mom to come and pick you up in the classroom.’ It is really sad to see that happening, especially my students in kindergarten being aware of that and being afraid of it. How am I going to ask her to be writing and reading if her mind is somewhere else?

What was your biggest misconception that you initially brought to teaching?

When I started teaching, my biggest misconception was that parents didn’t care, that families didn’t care. Especially my first year, when I used to send homework or I called them and they didn’t come. Once I got to know the community and the families, I learned that it’s not that they don’t want to help. Sometimes it is that they don’t know how, they don’t have the time. Many of them work two different jobs. I have to put myself in their shoes to see what their lives are like and understand, it’s not that they don’t care, it’s many different factors.

Is there anything about being a bilingual teacher that makes your job challenging?

We need to find ways to get things in Spanish. We’ll get the translations, but they’re not really true translations. Of course, we need to come up with our own, but it is more time. I don’t mind at all, but that’s something that discourages many teachers to go into bilingual [education].

What object would you be helpless without during the school day?

My Smart Board. We use it for everything. We do a lot of writing, and it’s not only me, it’s the students as well. One of my goals is for them to lead the class. I’m going to just be like the guide. It is your classroom — that’s what I tell them.