Many of America’s teachers expected to spend some of this school year teaching to a screen. They just didn’t realize their students would be in front of them in a classroom, too.

As schools reopen their doors, it’s becoming more common for teachers to have both virtual and in-person students on their rosters every day. In many places, that’s because students have been split into groups to allow for smaller classes. In other cases, families have opted to keep their children home, but they were not assigned a remote teacher.

Making these hybrid plans and all-virtual options work is a staffing challenge for school leaders and a child care problem for families. But it’s also becoming an instructional nightmare, even for experienced educators.

Teachers across the U.S. who are juggling in-person and virtual students simultaneously say their quality of instruction is lower than it normally would be, as they try to keep themselves positioned in front of cameras, keep the in-person students from feeling frustrated, and keep moving through their actual lessons. The result is they’re struggling to reach the students who need their attention most.

“You want me to be there for the in-person students, and there for the remote kids,” said Matt Alvut, a middle school teacher in Brockport, New York. “I don’t feel like I’m getting either one.”

As with remote teaching this spring, teachers who’ve been at this for a few weeks say they’ve gotten a little better with practice. But the time and energy it’s taking, they say, raises real questions about how long they can keep it up.

“The idea of this being sustainable long-term is still a big question,” Alvut said.

Divided attention, divided time

Melissa Boneski has a dozen kindergarten students in Bridgeport, Connecticut who come to school five days a week and another six who are fully virtual. She spends much of the day carrying around an iPad with the camera trained on her, livestreaming.

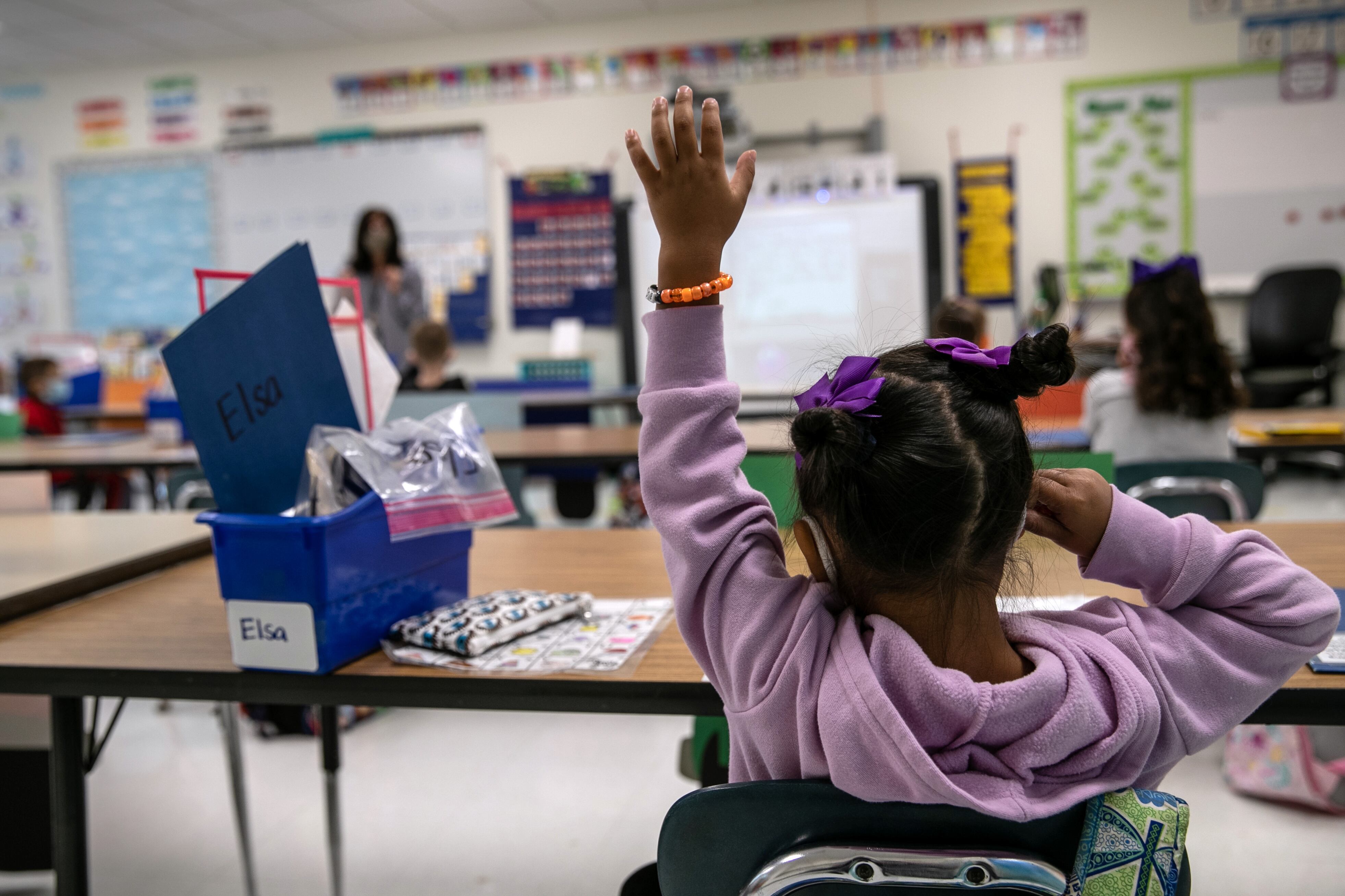

If she steps out of view, her students at home shout her name. When she tries to call on her online students, the students in front of her raise their hands, not remembering they have classmates who aren’t sitting with them.

“I say, ‘OK, I’m going to look at my online kids and have them answer this question,’” Boneski said. “They’re just like: ‘But I’m right here, I know the answer!’”

Kindergarten also feels less like kindergarten right now. Usually, Boneski would spend lots of time teaching in small groups, and students would play and work at centers around the room. But the protocols for sanitizing toys and games between uses would take up too much instructional time, so those materials aren’t in the classroom.

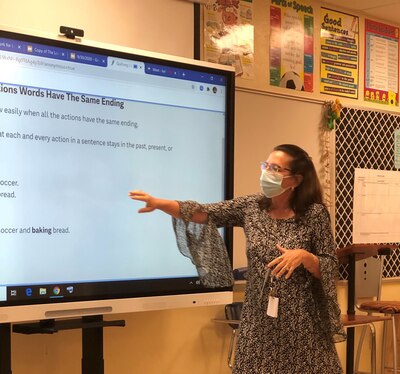

To stay visible to her online students, she doing a lot of teaching near her interactive whiteboard, a method she rarely used in the past. That creates a lot of physical distance between Boneski and some of her students.

“My farthest kid from me is probably around 20 feet away,” she said. “I can’t even see his work book. I don’t even know if he’s on the right page.”

To make virtual students feel included, fun fall crafts can’t be spur of the moment. She has to include all the materials in the students’ monthly take-home packets, which she makes on her own time.

“I’m trying my best, but obviously no one has done this before,” Boneski said. “Every day I’m like: OK, let me try to do this differently, and see if this works.”

The workarounds aren’t working

Christine Perry has found that many of her usual teaching strategies don’t work when half her class is in front of her and the other half is at home — no matter how many workarounds she tries. Her class of 18 fourth-graders in suburban Cleveland is split into two groups that come to school on alternating days.

“I’m constantly trying to make it better because I know this isn’t anything close to what I’m normally like as a teacher,” said Perry, who’s taught for nine years.

Recently, she’s been teaching her fourth-graders about maps. Typically, she’d ask her students to move around the room as they learned about cardinal directions, and then guide her students in taking notes. But her students in the classroom aren’t allowed to get up from their desks, and her students at home had a hard time following along. She tried a different note-taking method, but her students at home struggled to see how to fold their paper over video.

Without an interactive whiteboard, making herself visible to both groups at the same time has been the hardest part. Running back and forth from her laptop to her projector didn’t work. Now, she’s mostly staying at her desk with a document camera so the students at home can watch as she writes on a mini dry erase board. But she writes it a second time for the students in her classroom because the camera projects it backwards — something she hopes can be fixed.

“How do you cater to students that are having problems at home, but still not make it awful for kids that are in class who’ve heard you repeat yourself five times?” she said.

Perry knows this format has been a particular struggle for the handful of English learners in her class.

“There’s no way that I can give them the level of attention that they need,” she said. “I can tell by what they’re saying and how they’re responding — or rather not responding — that they really don’t understand what’s going on.”

In-person students outpacing their virtual classmates

Vincent Miller teaches five high school math classes in person and one super-size virtual class of 40 students. Since his district in Polk County, Florida started again in late August, he’s noticed a worrying divide: His honors geometry students who come to school are about two weeks ahead of their virtual peers.

“The pacing is totally different,” he said. “I know I’m ahead in brick and mortar. That’s a 100% fact.”

Miller, who won his district’s top teaching award earlier this year, says lessons that may take a day to explain in person are taking two or three days to review virtually. Some students are still learning how to upload their digital assignments and make PDFs interactive. And many of his virtual students regularly show up 15 to 20 minutes late to class, while some don’t come at all.

“I don’t think the kids can’t do it,” Miller said. “The effort is different.”

He’s also found his school day getting longer as he tries to respond to the texts and emails pouring in from his virtual students while managing his in-person teaching schedule.

“When you have a fourth-period virtual class and you have a whole day ahead of you, it’s very hard to get back to those students until you sit down at your house, or until you sit down at school at 5 p.m.,” he said.

Connecting with students across a virtual void

Judy Lehman has more than three decades of experience and has won an award for mentoring other teachers. But working with her 10th grade English students at home and online has her “feeling like a brand-new teacher again.”

Her school district in Palm Beach County, Florida, started virtually in late August and began offering in-person classes last week. But only around a dozen of her 140 or so students are coming in. Still, she’s overhauled her curriculum in an effort to keep her two sets of students on the same page.

“It takes much more planning, much more thought, much more creativity, to try to make it all flow,” she said.

Now, the main challenge is overcoming a feeling of disconnect.

Students at home and in the building start off class together, jumping into a 10-minute writing assignment with a prompt like “What would you do if you won the lottery?” But when Lehman asks students to share responses, the students at home can’t see the students in the classroom. (Lehman has to turn off the camera when students speak because she’s recording the lesson, and for privacy reasons can’t show student faces.)

Some students are struggling to stay online because of weak wireless signals at home, especially if they are using the district’s free internet at the same time as their siblings. About seven in 10 students at her school are from low-income families.

Lehman devised a workaround, asking students to log off the live video while doing certain assignments to reduce the amount of bandwidth they need, then monitoring them in a chat window or via email. But that means she may be watching three sets of students — on video, in person, and in a chat — at the same time.

Meanwhile, some students are logging in, muting themselves, and not participating. When Lehman doesn’t have body language cues to rely on, it’s harder to know if a student is stuck.

“It’s kind of like teaching into an abyss,” Lehman said. She finds herself saying: “Hello, hello? Are you there?”