For decades, “To Kill a Mockingbird” has been one of the most taught novels in the American educational system. Middle schools assign it, high schools stage dramatic adaptations, and teachers across the country regularly name it as one of their favorite texts. But long before teachers were thinking about Harper Lee, Harper Lee was thinking about teachers.

One of the very first articles Lee ever published was titled “Why I Entered Teaching,” which I discovered while working on my book, “Furious Hours: Murder, Fraud, and the Last Trial of Harper Lee.” Lee’s piece was not a memoir. She never taught, but her first job when she moved to New York City from a small town in Alabama involved editing an education trade magazine called The School Executive. Not long after she started working there, when she was only 23 years old, she snagged her first byline by summarizing a survey in which administrators, classroom teachers, and teaching students explained why they entered the profession. The article was forgotten partly because the magazine itself was, but also because it was so early in Lee’s career that she was “Nelle Harper Lee” on the masthead and “Nelle Lee” on her article; a full decade would pass before “Harper Lee” showed up on the cover of a book jacket.

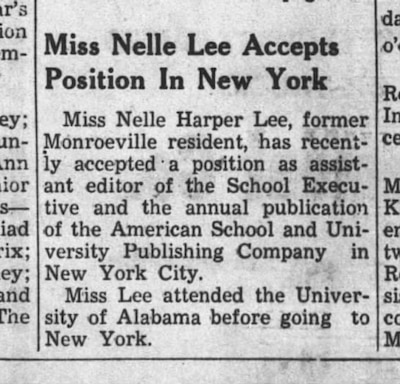

In April 1949, just after Lee dropped out of the University of Alabama, her local newspaper announced that “Miss Nelle Lee Accepts Position In New York.” The Monroe Journal kept a close eye on the Lee family, partly because it was owned by her father A.C. Lee, the model for Atticus Finch, who ran the paper for two decades alongside his law practice. Lee printed his daughter’s poetry and covered his four children’s birthday parties, school accomplishments, and church programs, but he also wrote his own (generally conservative) political editorials about everything from prohibition to fiscal responsibility to race relations.

Harper Lee had far less editorial freedom in her first publishing job. The School Executive was the monthly magazine of the American School Publishing Corporation, and it had roughly the same table of contents every month: a front-of-the-book section with an editorial note, conference calendars, and news of the educational world, followed by two other sections, one called “Schools in Action” with features on schools around the country and another called “Educational Planning” that evaluated curriculum, catalogs, equipment, and teaching aids.

Lee had been hired by the editor-in-chief, an Iowan named Walter Cocking who had spent most of his professional life in the South. Cocking had taught school administration at a teaching college in Tennessee before being named the state’s education commissioner; four years later, he was hired to be the dean of the College of Education at the University of Georgia, where he became involved in a school integration scandal that changed that state’s history.

Cocking had been hired to modernize the university’s teaching college, but when he proposed including a practice classroom for Black children as part of the college’s demonstration school, he was accused of being an integrationist. This was 13 years before Brown v. Board of Education and 22 years before Alabama’s Governor George Wallace would take his stand in the schoolhouse door to oppose the integration of the University of Alabama, so even that faint whiff of integration caused a panic among the university administrators, who fired Cocking, together with members of the college Board of Regents, at the insistence of Georgia Governor Eugene Talmadge.

The Cocking Affair, as the purge became known, led to Talmadge losing his reelection campaign, although by then Walter Cocking had already moved to New York to work for the Buttenheim Publishing Corporation, a family-owned publisher of several trade magazines, including The School Executive. As chair of the board of editors, Cocking wrote a short editorial for most issues, on everything from “Strengthening State Departments of Education” to “The Education of All Americans.” To do all the rest of the work, he hired a parade of recent college graduates — or, in the case of Harper Lee, a recent college student, since she had left Alabama without finishing her degree.

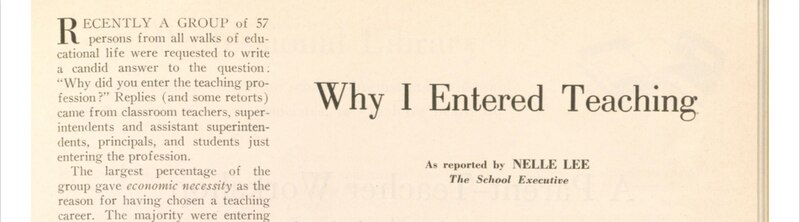

When I started on my book, I already knew that Lee had worked for The School Executive. But I was shocked, when I began looking through the issues published in the time she was there, to find one with an article she had written. As an editor, Lee’s name appears on issues throughout 1949, but on page 49 of the October issue is “Why I Entered Teaching,” under her byline. Other than articles and columns for the college newspaper and some book reviews and stories for campus literary magazines, this was Lee’s first “clip” — a big deal for someone who wanted to be a professional writer, even if it came from a magazine read only by educators and administrators, who paid three dollars a year for the privilege.

Lee was writing up a survey of some 57 people who all answered the question: “Why did you enter the teaching profession?” “Replies (and some retorts),” her article began, “came from classroom teachers, superintendents and assistant superintendents, principals, and students just entering the profession.” Their answers in the late 1940s are probably not so different from what a similar survey might reveal today. Some were inspired by memories of teachers who had changed their lives, others by a love of children and young people. Some felt a patriotic calling to help educate good citizens, including a young veteran of World War II. In another sign of the times, some had taken aptitude and interests tests that suggested they would be good at teaching.

Many of the survey respondents had been drawn to teaching for the financial security, although a few, conversely, complained about the money. Among the three who regretted becoming teachers, Harper Lee quotes one who wrote: “It is difficult for me to throw myself into teaching at $45 a week, when at present driving a truck and just dropping off packages for four hours a day I can earn $75 a week.”

But those were some of the only complaints, and while Lee structured her article in a way that acknowledged the underpayment of teachers, she ended on the profession’s most enduring virtues. “Teaching, if sincerely and honestly done, will give me an opportunity of giving my life a measure of significance,” Lee quotes one of the educators saying. Another survey respondent she highlights, who quit his job in the international division of a large corporation in order to teach, has the last word: “I have never been happier in my life. My work has been more than justified in terms of moral compensation. What greater satisfaction can one ask out of life?”

It’s just a page long, but a wonderful article: a time capsule of the teaching profession at mid-century, and a sweet, unexpected intersection between Harper Lee and the professionals who would later enshrine her novel in the national canon.

There is an important and interesting conversation happening now about the relevance of “To Kill a Mockingbird” to our country’s pursuit of racial justice and how we teach civic virtues like tolerance. For a long time, Lee’s novel has been one of the most banned books in the country, first criticized by conservatives who disapproved of its integrationist politics, then by liberals who disapproved of its use of racial slurs, and all along by censors of all persuasions who object to its depiction of rape and incest. Lately, though, the novel’s detractors are not calling for a ban or censorship, just retirement: taking it off of syllabi in order to make room for books by a more diverse group of authors, offering students work written with an eye to the current fight for racial justice, not one from the last century.

These are urgent questions, and I enjoyed discussing them with educators around the country when I was on book tour for “Furious Hours.” And I like to think Lee would have understood more than anyone how carefully teachers consider what they teach. She had a high view of education, and abiding appreciation for educators; in fact, it was one of her high school English teachers who proofread “To Kill A Mockingbird” just before its publication. Even in old age, when she had stopped signing copies of her novel or replying to much of her fan mail, she continued to respond to teachers who wrote her and school children who asked for her autograph. Those letters are so voluminous they could constitute their own archive, and some have been shared publicly since she died. And so there is something wonderful about knowing that her first professional publication was a love letter to the very profession to which she would spend the rest of her life so indebted. “Why I Entered Teaching” was the title of Lee’s article, but for more than a few teachers over the last six decades, Lee’s own novel is an answer to that very question.

Casey Cep is the author of “Furious Hours: Murder, Fraud, and the Last Trial of Harper Lee,” out this month in paperback from Vintage Books.