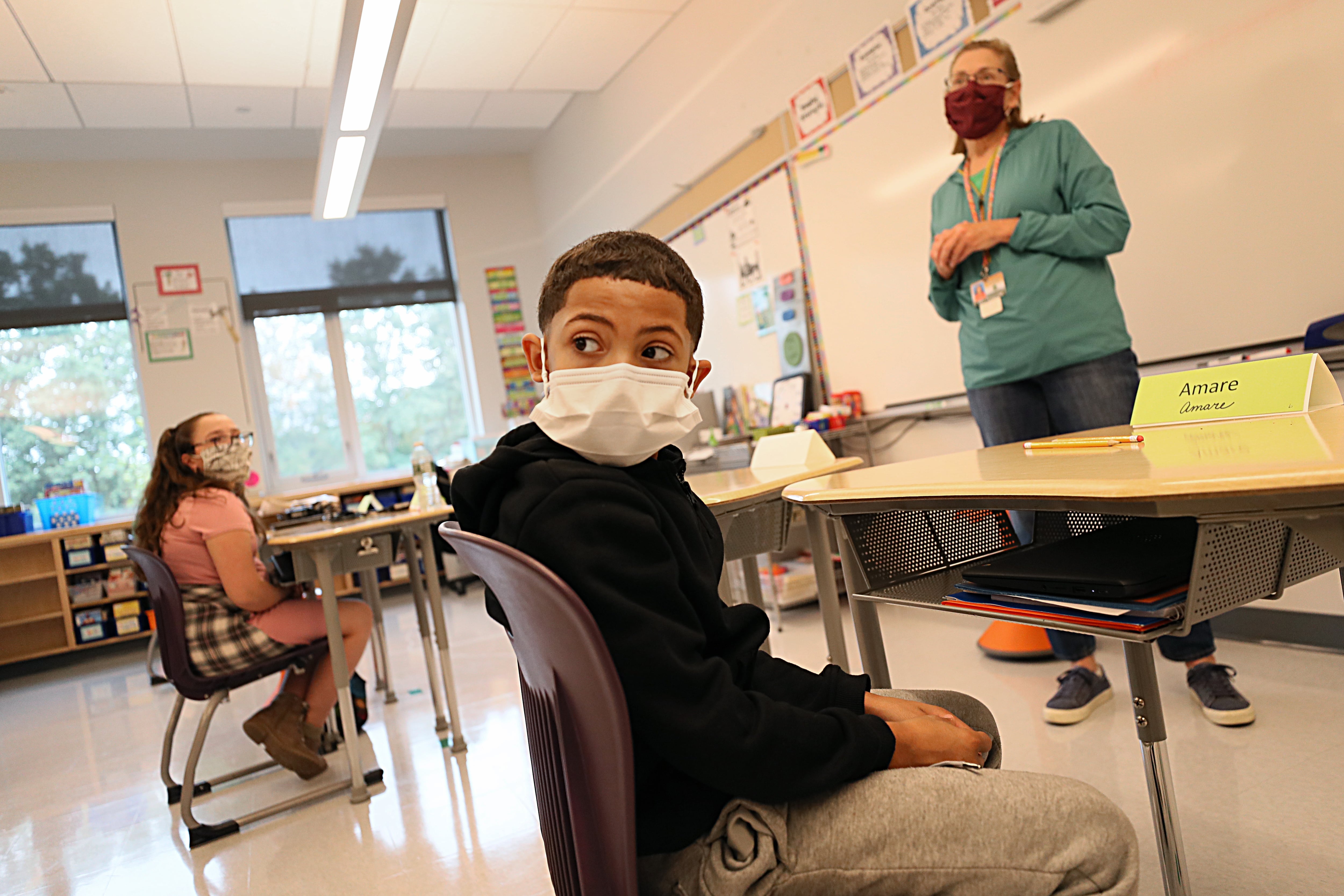

Rising COVID cases are derailing plans by school districts across the country to reopen their buildings and pushing some schools that had opened to close once again.

Just this week, the Detroit school district suspended all in-person learning until January. Health officials ordered schools in Indianapolis to do the same. Philadelphia put its plans to bring young students back at the end of this month on hold indefinitely. And some of Colorado’s largest districts are reverting to remote learning after quarantine requirements made staffing buildings too challenging.

They join schools in Newark, Boston, San Diego, and many smaller districts in scaling back or scrapping their school reopenings — an illustration of how the country’s failure to contain the coronavirus has continued to disrupt the education of millions of students. Some of the school districts now closing buildings completely had already been open only for students with disabilities, English learners, and young students, for whom virtual learning is a particular strain.

Many districts in places with significant COVID caseloads remain open, though, highlighting the widely varying approaches to school shutdowns being taken by school leaders, governors, and even health officials.

The inflection point follows a period when more and more schools opened with apparent success. Public health experts have grown cautiously optimistic that it could be done relatively safely during the pandemic, with certain safeguards and as long as the virus was not spreading through a community at extremely high rates. But the test positivity rates in many parts of the country have now reached new heights.

“The bottom line is if community rates get to a certain level and higher, schools are going to have to close,” said Rebecca Haffajee, a health policy researcher at RAND. “Now where exactly that threshold is, is the million dollar question.”

Those districts may be joined soon by New York City, the country’s largest. Officials there are warning that the city is approaching its self-imposed threshold for closing schools — a 3% positivity rate, an unusually low limit. (The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest guidance describes a 14-day positivity rate over 10% as indicating the “highest risk” of transmission in schools, while under 3% indicates “lowest risk.”)

Notably, the positivity rate among randomly tested school staff and students in New York City remains very low: 0.18% since mid-October.

Nationwide, over 60% of students attend school in a district offering some form of in-person learning, according to a recent estimate by the website Burbio, which tracks school reopenings. That figure marks a sharp increase from the beginning of the school year, though it has flatlined of late.

(That’s different from what share of students are actually attending school in person, since many districts allow students to choose fully virtual learning. In a late October poll, 54% of parents said their child was still learning exclusively online.)

The growing drumbeat to get schools to reopen appears to have been overtaken, though, by rising rates and new staffing challenges.

Take Jefferson County schools, one of Colorado’s largest districts, where schools have remained open even as test positivity rates eclipsed 10%. Janitors there are struggling to keep up with the “deep cleanings” the district has promised whenever a school has a reported case. The district is struggling to run its bus routes because too many drivers have had to quarantine. And administrative staff are regularly covering classrooms of teachers who are out.

The district is now set to have all middle and high school students go remote next week, with elementary schools following later this month. (Preschool and some services for students with disabilities will continue in person.)

Philadelphia, meanwhile, has not opened buildings yet and announced this week that it will not do so “until further notice,” now that its COVID test positivity rate is above 9%.

“We hope to see those children return before the spring,” Superintendent William Hite said, as the city’s top health official warned it was “entering a dangerous period.”

In Detroit, where schools superintendent Nikolai Vitti has pushed for months to keep school buildings open for students who want in-person learning, the decision to close them came in anticipation of the city reaching a 6% test positivity rate this week.

“It is what it is at this point. Cases are going up. There’s nothing I can do or say,” said Detroit parent Ebony Graves. “I’m a healthcare worker and I know how crucial it is right now.”

But the changes are deeply frustrating to others, who find themselves in a childcare bind or watching their children struggle with remote learning. “He likes going to school,” said Indianapolis parent Steven Thompson, referring to his fourth grade son. “And his learning needs, in my opinion, require that engagement and that face-to-face interaction.”

Los Angeles and Chicago, two of the country’s largest districts, have also not opened for any in-person instruction, and it remains unclear when they will. Cases in Los Angeles County are rising (test positivity rates are around 5%), and the school district there says reopening won’t happen until January at the earliest.

Chicago had hoped to welcome some students back into buildings soon, but rising cases in the city — test positivity rates are at 14% — and an ongoing dispute with its teachers union means there is no clear reopening date. Eight of Illinois’ 10 largest districts have remained fully virtual or recently put their reopening plans on pause.

The setbacks are coming as Thanksgiving and winter holidays approach. That adds yet another layer of complication, as some fear families who travel and then return to schools could spread the virus even further. A handful of districts where schools are open are already planning to avoid this by closing buildings from Thanksgiving until the new year.

Still, in some large school districts, buildings are open and have been for some time. In Florida, schools in Miami-Dade (where daily positivity rates have recently ranged from 6% to 9%), Broward (6% to 8% positivity), and Hillsborough (7% to 9% positivity) counties remain open, even as cases have risen locally. The same is true in Texas, where schools in Dallas and Houston remain open. (Houston hit 7% test positivity, the district’s previous benchmark for closing schools, in late October, but changed its protocols.) State officials in both places have aggressively pushed schools to reopen.

Haffajee of RAND said the coming months would be critical for containing the virus enough to allow more schools to open. To get there, she said, individuals need to do their part to reduce the spread, and governments should prioritize schools over other public places like bars, restaurants, and gyms.

“If we want to keep schools open, we have to make some other sacrifices,” said Haffajee.