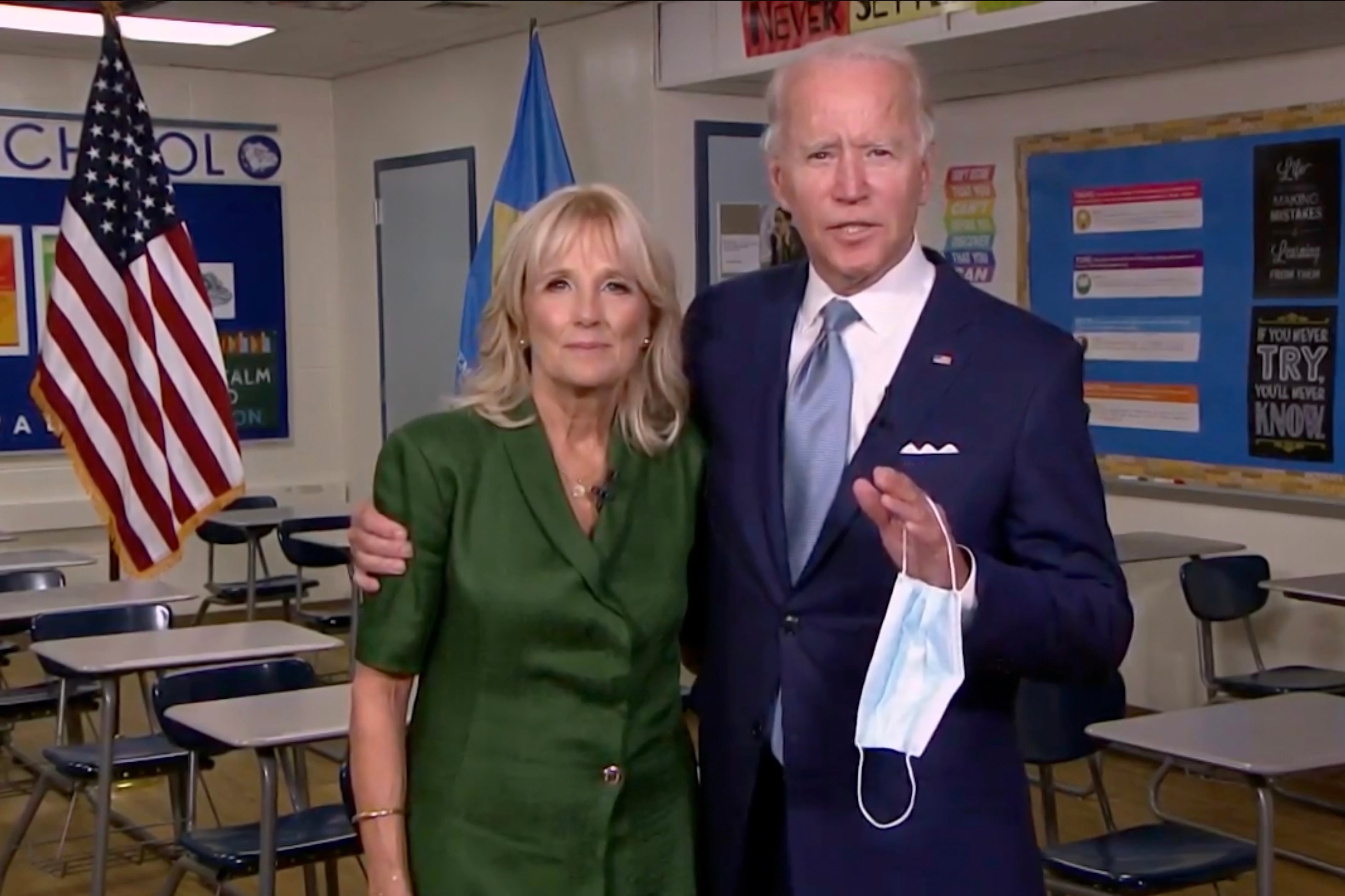

In his victory speech, President-elect Joe Biden said it was a “great day” for America’s educators because “one of your own” would be in the White House, referring to his wife, Jill Biden, a member of the country’s largest teachers union.

When Biden selected an education transition team, four of the 20 members worked for national teachers unions.

And among the names circulating for potential education secretary picks are two national teachers union leaders: Lily Eskelsen García, who recently headed the National Education Association, and Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers.

No matter who ends up in the top job, teachers and their unions are poised to help shape the Biden administration’s approach to federal education policy.

“Joe and I will never forget what you did for us,” Jill Biden told the heads of the NEA and the AFT on Monday as she thanked them for their members’ support during the election. “Joe and Kamala will not only listen to you, they’re going to make sure that your voices are leading this movement. Educators, this is our moment.”

What that moment looks like, and where that influence might be felt most clearly, are the key questions now.

Had the pandemic not upended this last school year, the answer might have been on issues like big funding boosts for public schools serving low-income students and a tougher stance on charter schools. Those union-aligned promises were a part of Biden’s campaign platform.

Now, though, it’s clear that the next education secretary — union leader or not — will spend much of their initial time dealing with the pandemic. That puts the details of a future pandemic aid package front and center, along with unions’ hopes that it could insulate educators from layoffs and even add to their ranks.

Teachers unions, congressional Democrats, and the incoming Biden administration align on wanting more money to help K-12 schools reopen and aid for state governments, which could be used to buoy school district budgets and prevent educator layoffs. Already, The Pew Charitable Trusts estimates nearly 670,000 public school staffers have lost their jobs during the pandemic, though many of those losses may be temporary.

“They’re going to want a quick infusion of funds, in particular to save educators’ jobs,” said Bradley Marianno, an assistant professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas who studies teachers unions. (There is evidence that this would be good for the broader economy, too.)

Biden’s campaign has also said coronavirus relief aid could be used to hire more teachers to make class sizes smaller during the pandemic — a key way to encourage social distancing — and to help students with mental health needs.

What ultimately happens, though, is likely to depend on control of the Senate, which now hinges on two runoff elections in Georgia. Negotiations over that legislation have dragged on for months, and Republicans generally don’t support a large sum going to state governments.

Teachers unions also could make their influence felt in the details of any eventual law.

The CARES Act, the last big comprehensive package that passed in March, set aside just over $13 billion specifically to help K-12 schools. School districts could spend that on staff salaries or things like technology, cleaning supplies, and building improvements. This time around, teachers unions could pressure the Biden administration to insist on “clear parameters” around how much should be spent on educator salaries, Marianno said.

A Biden education department also could provide written guidance to states about how to spend new dollars in a way that’s more favorable to teachers and their unions. DeVos, notably, told governors they likely couldn’t give any of their $3 billion in CARES Act dollars to teachers unions.

And there are other ways teachers want to influence the Biden administration’s pandemic response. Teacher unions will likely continue to push for a more cautious approach to reopening schools, with the education department offering support for school districts that are choosing to stay remote — a decision Education Secretary Betsy DeVos (and public health experts, in some cases) has repeatedly criticized.

“The unions have been pretty clear that they don’t want schools to reopen until it can be very safe to do so,” said Katharine Strunk, an education policy professor at Michigan State University. “If we do have someone [as education secretary] with a strong union background, we might see the school reopening conversation take a very different shape.”

Other parts of Biden’s education agenda will likely be difficult to advance if Democrats lack control of both houses of Congress. How much influence unions have, then, could depend on whether the Biden administration is able to tie its pre-COVID priorities to pandemic relief.

Before the pandemic hit, one of Biden’s biggest education campaign proposals was a pledge to triple Title I funding for schools with greater shares of students from low-income families. He proposed that some of that new money could be used to raise teacher pay in high-poverty schools.

If Republicans control the Senate, they likely wouldn’t go along with a big spending boost like that, but they may accept some modest increases, said Michael Petrilli, the president of the Fordham Institute, a conservative think tank.

“There’s going to be a lot of competing priorities and any sort of big, transformative education law that would create longer-lasting funding increases is probably not going to be forthcoming right away because most of the attention is going to go to the coronavirus,” said Jon Shelton, an associate professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay, who wrote a book about teachers unions.

But another avenue for raising teacher pay could be through addressing learning loss in the months to come. In his plans, Biden has said there’s a need to improve remote learning and help students catch up after missing instruction during the pandemic, but he hasn’t spelled out details yet.

“We’re hearing from teachers that they would be excited about substantial increases in teacher pay that go along with a longer day and/or a longer school year to help students recover from this missed time,” said Evan Stone, the co-CEO of Educators for Excellence, a group that pushes to include teacher voice in education policies.

Another area to watch is testing. On the campaign trail, Biden criticized high-stakes testing, echoing the concerns of teachers unions. DeVos allowed states to cancel state standardized tests this year, and Biden’s education secretary will have to decide whether or not to do that for a second time.

Teachers unions may have a “window” to have a larger debate about the value of those tests, said Strunk, of Michigan State.

Union leaders are already pressuring the Biden administration to cancel state tests again.

“Of course you’re not going to impose the testing program that has existed over the last several years, because that’s unfair,” Becky Pringle, the head of the NEA, said recently. “Do we explicitly articulate that in our priorities? Yes.”

But many civil rights groups and others support keeping the tests as a way to document opportunity gaps between students, which could be especially important during the pandemic. If the Biden administration doesn’t grant blanket testing waivers, teachers unions may seek to ensure that state tests aren’t tied to teacher evaluations and school ratings.

“There might be a continued push to make sure that testing isn’t used to hold any type of accountability pressure upon teachers, but is instead used as a tool to guide instruction and focus of priorities and resources,” Marianno said.

Charter schools are likely to be another pressure point, though many observers agree that issue is likely to go on the back burner for now. On the campaign trail, Biden said he would seek to prevent federal funds from going to for-profit operators, but he hasn’t said what he intends to do with the federal grant program that funds charter school expansion.

Charter schools are still popular within parts of the Democratic party, especially among Black and Latino parents. Teachers unions may press Biden to spend less on the expansion of charter schools, or to put stipulations on how that money can be spent, but the administration may want to avoid a contentious fight on that front.

Where teachers unions definitely stand to gain from the Biden administration is from a new education secretary who is likely to strike a more positive tone about public school educators than DeVos. Biden has pledged his education secretary will have experience teaching in a public school.

“That is both symbolically important and it is really important to change the relationship between the federal government and teachers, which right now is caustic and antagonistic,” Stone, of Educators for Excellence, said. “They could shine a light on the amazing work that educators are doing in a way that builds some positivity at a time when there is just a lot of negativity and fear.”

Biden has said his education department will be “teacher-oriented” and that policy will flow “from the teachers up,” rather than “from the top down.”

Teachers union leaders, for their part, aren’t worried about facing public backlash because of their newfound influence. Pringle recently told the New York Times she knew Biden would “take the slings and arrows for being ‘too close’” to the teachers unions, but that Biden will “be able to say, ‘Not only did they help me get elected, they help me lead in a bold way.’”

Many educators hope the new education secretary’s classroom teaching experience will make them more likely to seek out teachers’ opinions.

That’s happened in the past. During the Obama administration — which had often-tense relationships with teachers unions — teachers served as “ambassadors,” according to Deborah Delisle, who was the assistant secretary of elementary and secondary education for three years under Obama and is now the president and CEO of the Alliance for Excellent Education, an advocacy group.

During that time, she said, the teacher ambassadors had offices on the same floor as the education secretary and often weighed in on policy during meetings.

“For educators, the main goal is to always be at the table,” said Marisol Garcia, the vice president of NEA’s Arizona state teachers union, who helped advise the Biden campaign as one of the leaders of Educators for Biden. “A lot of times we’re at the secondary table, or in the back row.”