The questions came on Zoom, from students logging into morning meetings and virtual lessons from their bedrooms and kitchen tables. They came in person, from masked children raising their hands in socially distanced classrooms.

“When will we know?” they asked. “What does this mean?”

Many Americans stayed up far too late monitoring the presidential election, then awakened to an unclear outcome. For teachers across the nation, that meant explaining the uncertainty to children too young to remember any other presidential election and to teens whose questions run deeper than just who won or lost.

The conversations — some well-planned lessons, others more off-the-cuff — look different than during any other presidential election. They come during an uncontrolled pandemic that has upended daily life and changed our very concept of school. They come amid a nationwide racial reckoning and an examination of social justice and equity. They come after four years of a presidency that has unearthed and deepened divisions.

Chalkbeat reporters observed classes Wednesday and spoke to teachers nationwide about how they addressed students’ questions on a day when answers were hard to come by.

Tracy Garrison-Feinberg was deep into a lesson on the Electoral College when a student interrupted the video session with news.

“She put in the chat, ‘Uh, breaking: Wisconsin just got called for Biden.’ And we all just sort of stopped,” Garrison-Feinberg recalled. “I had a 12-year-old seventh grader call Wisconsin for me.”

Garrison-Feinberg, a seventh grade humanities teacher at Clinton Hill Middle School in Brooklyn, spent the last week planning alongside her colleagues for what Election Day might bring. She felt prepared to tackle whatever came up, but also knew there would be these unexpected moments. “I said, ‘Let your students drive you where you need to go.’”

So Garrison-Feinberg kept her lesson plans “loose” and encouraged her students to stop her along the way with questions. When the electoral map changed mid-lesson, she hit pause on their debate over why the Electoral College was created in the first place and let her students discuss the news.

She also followed their lead earlier that morning, during an extended advisory that the school planned to give students time and space to talk about the election. By the time Garrison-Feinberg had logged into the small-group session, ready with a prompt, her students were already excitedly asking each other why Georgia’s results still hadn’t been reported. Another student began to explain how the votes were tallied, holding up a color-coded electoral map on her phone that she had pulled up from CNN’s website.

Garrison-Feinberg tossed the prompts she had planned just let the conversation flow. As she listened, her own sleepiness from staying up past 1 a.m. faded.

“Kids were really animated,” she said. “It was one of the things that energized me. I thought, ‘OK, I can get through the day now.’”

As the election drags on without a clear result, Garrison-Feinberg said her goal as a teacher is to help students think about what comes next. She’s planning lessons about what it means to be a citizen, and modeling how to have tough conversations with people who don’t agree. And whoever wins, she wants students to know the importance of holding elected officials responsible for the promises they’ve made.

“Our job is to prepare these future voters. That’s it. That’s what we’re trying to do,” she said. “Democracy continues to be a work in progress for the people who show up.”

— Christina Veiga

In Denver, high school teacher Kade Orlandini started her virtual student council class with a set of three questions. The first: How are you doing today?

Students responded by typing their answers — or in a few cases, drawing them, emoji-style. Orlandini narrated the responses as they came in.

“Some feelings that I’m seeing — we have a lot of anxious; we have a lot of tired,” said Orlandini, who teaches at John F. Kennedy High School. “I’m seeing some optimistic … I see the sweating GIF. Scared. Stressed, stressed, tired, tired, stressed. Yep, okay.”

This class of more than 30 students has been studying the election this fall, taking a close look at the presidential race as well as local races and the long list of measures on Denver’s ballot. They also organized a mock election at their 920-student high school in the southwest part of the city. (To their chagrin, Kanye West got a fair number of votes.)

On Wednesday afternoon, the students discussed the ongoing national vote count. Orlandini asked them to expand on why they were feeling scared and anxious.

“Even if my life isn’t as much at risk, I feel like many people are,” said one girl.

“I agree,” her classmate said. “Even if I’m not affected, I know friends and family members who are. ... If Trump wins, what’s going to happen to them, you know?”

Orlandini paused. “Do you mind saying what you’re talking about?” she said.

“I’m talking about DACA,” one of them said. “And it’s very personal because my sister has DACA, and my family is super anxious because we’re not sure what’s going to happen.”

DACA is Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, an Obama-era policy that provides legal protections to undocumented young people. Trump has been trying for years to end it. Most students expressed concern about what another term for the president would mean.

“A lot of us were not able to vote this year,” another student said. “But I’m going to be 18 ten days after Inauguration Day. I am going to be dealing with the consequences of this election for the next four years, and I didn’t even get to vote.”

— Melanie Asmar

As Brandon Moss was preparing to teach his 10th grade civics class at the School at Marygrove in Detroit, he thought back to 2016.

The day after Donald Trump’s upset victory, many of his students were caught off guard. Some of his LGBTQ students were in tears.

“Teaching in the moment of the elections, sometimes I think it backfires,” Moss said.

If a student feels defeated, it can lead to apathy, he noted. “Apathy is the nightmare of every single civics teacher,” he said. “That’s what keeps us up at night.”

So in the weeks leading up to Election Day, the ninth-year teacher sought to prepare his students. He taught them how to question information in the media, including headlines meant to stir emotion. By thinking critically, he said, students may be less consumed by their emotions.

“I’m trying to give my kids a toolbox to defend themselves,” he said.

The furious pace of the news cycle, not being together physically during remote learning, and occasional technical glitches made the work more challenging.

As his class met Wednesday with the fate of the race unknown — including in the key battleground of Michigan — Moss again heard a lot of frustration and disappointment.

Many students were upset over President Trump’s baseless early claim of victory. One student didn’t want to speak to some family members who used toxic rhetoric.

Moss once again fears students will disengage because of the tense political climate. But ultimately, he hopes learning about the democratic process will empower them and give them the confidence to talk to people with different views.

“You won’t try to burn bridges down,” he said. “You’ll want to build them. But it takes practice.”

— Eleanore Catolico

At 8:45 a.m. in Indianapolis, Victory College Prep teacher Megan Kinsey pulled up a map of election results for her second-period high school government class.

She had a question for her students: Who did they think was winning the presidential election?

But after that, Kinsey wanted them to be asking the questions. After sorting through the uncertainty — why didn’t we have full election results last night? — here’s what they wanted to ask their teacher:

“You voted for Biden, didn’t you?”

“Why do you think that?” Kinsey asked.

It wasn’t because she didn’t want to tell them. She already told them at the beginning of the year that she generally votes Democratic, disclosing her politics to set the stage for honest discussions as students prepared to research issues and form their own opinions.

“Why do you think that?” and “How do you know that?” have been central questions Kinsey pushes her juniors and seniors to ask and answer.

“If you see a tweet, you question it. If your parents tell you something about politics, question it,” said Kinsey, who encourages her students to question her, too. “The No. 1 thing I want you to do this year is push back.”

Her classes at Victory College Prep, where about two-thirds of students are Black, have a mix of students who identify as Democrats, Republicans, or third-party supporters. Students debate and often disagree, but the point is to learn something new, not to attack others’ beliefs.

She lets her students ask about her stances at the end of each lesson, only after they’ve formed their own opinions. So they knew where she stood on immigration, health care, and taxes.

Kinsey told them she also supported how Biden’s policies would benefit low-income and middle-class Americans and where he stands on policing.

I heard he wants to defund the police, one student said. What does that mean?

If Biden wins, another student wanted to know, what does that mean for taxes?

Those questions, she can answer. But her students have other concerns. If Biden wins, will white supremacists retaliate in some way? Will Trump give up power?

Those questions, she couldn’t answer.

— Stephanie Wang

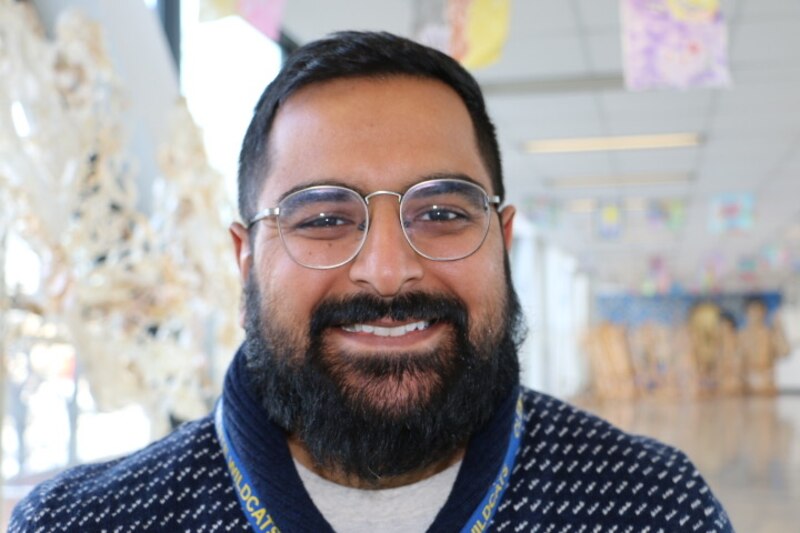

Even before senior seminar teacher Mueze Bawany began his first class, students were popping into his morning office hours. Their big question: What’s going on with the election?

“It’s been a wild day,” said Bawany, who teaches at Clemente Career Academy, a high school in Chicago’s Humboldt Park neighborhood.

Once class began, Bawany tried to use the uncertainty of the election as a teachable moment on media literacy.

“What you see on Facebook about the election posted by a random friend — take it all with a grain of salt,” he said, pointing his students to resources like The New York Times election tracker. “The only thing we are certain of is the election is still going on.”

In 2016, Bawany, who is Pakistani-American, was teaching at John Palmer Elementary in the city’s diverse North Mayfair neighborhood. Many of his students were Muslim, and he offered them emotional support following Trump’s election.

“They had all this information and perspective from their parents. To the Muslim community this guy is terrifying,” he said. “They were really tough moments for the kids.”

This year, working with high schoolers, he’s seeing a lot of anxiety — and apathy.

“We have done voter outreach. I’ve tried to register kids,” he said. They aren’t convinced their vote matters, but Bawany has tried to convince them otherwise. “I tell them: ‘Voting is not going to dismantle the system, but it’s harm reduction.’”

He’s also tried to bring the history of Humboldt Park, the heart of Chicago’s Puerto Rican community and the center of community aid efforts for decades, into his election discussions. “Communities like ours have always relied on each other, and they will continue to,” he told students.

Still, working remotely has made connecting with students in an uncertain time more challenging.

While students could just wander into his classroom during in-person schooling, Bawany said he tries to be careful about bringing up sensitive topics in a remote setting.

“I tell them it’s difficult to navigate this stuff,” he said. “Just let me know, and I got you.”

— Yana Kunichoff

On a typical day in Charlie McGeehan’s 12th grade humanities class at the U School in North Philadelphia, only 15 or 20 students out of a class of 30 show up — and none turns on the camera. Wednesday was no different.

McGeehan did what he could to entice the students to participate in the discussion using a “jam board” — a virtual bulletin board of sorts — and the Zoom chat.

The students at the school, which draws most of its students from parts of North and West Philadelphia, and Kensington, all areas that are primarily Black and Latino, were well aware that Philadelphia is one of the most important battlegrounds in the country.

Still, it was difficult to get them to engage.

At the start of the session, McGeehan livestreamed the scene of ballots being counted at the Philadelphia Convention Center, ballots that could make the difference in the election.

What few thoughts the students shared were brief. One was blunt, writing: “I don’t really care who wins.” Another said: “In honesty both are bad but I hope Biden wins.” A third wrote, “Will the world be different if Biden wins?” Then there was the student who said, “I honestly got nothing.” And the one who asked, “Who voted for Kanye?”

Two male students said they were old enough to vote, but didn’t. Another said he went, but had to cast a provisional ballot. A young woman named Inez was the most engaged, but she won’t turn 18 until Christmas Eve. She really wanted to vote, but also complained, in so many words, that the candidates are two old white men and not part of her world. Does it really matter who the president is?

“I mean, we know voting is important but since Trump got into office it’s been stressful dealing with him for the past four years,” she said, following up with, “When are we going to have a female president?”

The class has discussed the importance of counting all ballots and how much every vote matters. McGeehan said to the students: “I’ve been trying to push you all to get engaged and vote, it’s been an uphill battle. “

But why?

One student said the presidential campaign is just not part of most students’ reality. Especially during the pandemic, they are cooped up, playing video games, and existing in their own world.

“If you are detached from everything going on in the world,” he said, “does voting really matter?”

McGeehan said later that he thought it was more complicated than students simply tuning out. “They just didn’t hear a candidate really speaking to them or who they connected to or who seemed to get what they cared about,” he said later. “I could see them caring more if they really connected to a candidate.”

— Dale Mezzacappa

Dan Wolford is always ready to throw out his lesson plan when students want to talk about politics. It usually starts with a student question. Hot topics this year included the electoral college, the two-party system, and voter suppression.

In 2008, when Wolford was the same age as many of his social studies students at Martin Luther King High School in Detroit, his civics teachers led wide-ranging, impromptu discussions about the presidential election.

That approach has guided Wolford in 2020.

“It really made me feel that as a social studies teacher, our role is to help students understand that their opinion and their voice really matters,” he said.

Student voices have been rarer in Wolford’s classroom this year, thanks to the pandemic. His class meets by video conference, and while most of the students log in for sessions, he said only 1 in 6 typically participates in class discussions.

Those students, however, are eager to talk. As Michigan officials raced to count ballots Wednesday, Wolford said his virtual classroom was shot through with anxiety. One student said she hadn’t slept the night before. Another, near tears over efforts to reduce voter turnout in U.S. cities, said he felt that the government doesn’t want Black people to be heard.

“They have just seen so much more” than students of the same age four years ago, Wolford said, pointing to protests over police brutality that have continued in Detroit during the months after George Floyd was killed by a police officer in Minneapolis.

“Even though there’s fewer voices [in class discussions], those voices seem louder, they seem more focused. They understand that their livelihood is at stake, their future is at stake. They’re paying attention.”

— Koby Levin

Anxious, content, skeptical. Peaceful, anxious, frustrated. Hopeful, pensive, sleepy.

Each of the ninth and 10th graders in Kat McRitchie’s contemporary issues class at Memphis’ Crosstown High School shared what they were feeling Wednesday afternoon as officials across the country continued to count votes in the presidential election. Mostly they were anxious, but not discouraged.

Even though election night played out how she thought it would, McRitchie was surprised at her own anxiousness the day after. “We’ve been all over the map in the last 24 hours, which is part of being human,” she told students over video conference.

McRitchie, who has worked in Memphis schools for over a decade, has led the 12 students in dissecting the election cycle since the school year started all online in August: the conventions, the debates, and of course, voting and the election.

The class — which includes Black, white, and Hispanic students, as well as LGBTQ students — mostly backed Joe Biden, with just one student supporting Trump. But an ideology matching quiz they took matched nearly every student with Green Party candidate Howie Hawkins.

As students expressed their emotions, McRitchie leaned in.

“What are you anxious about?” she asked a student.

“I just don’t think he has good intentions to help everybody,” the student replied about Trump. “He puts himself first before everyone else.”

What’s most important to McRitchie is for students to build skills to examine and explain their point of view, understand another’s, and weigh diverse opinions — a skill sorely lacking in American society, she said. To do that, she ditched the idea that teachers should be neutral instructors. Instead, she shares her opinions and models for her students how to create an inclusive space for vastly different views. After all, it would only take a quick Google search for her students to find out about her activism across the state to reduce gun violence.

“In Memphis, when you’re teaching primarily Black students and primarily students in poverty, I think it’s important, especially as a white teacher, to not have kids wonder where you stand,” she said.

During the 2016 election, McRitchie was coaching other social studies teachers through a local teacher training organization and saw many struggle with how to interpret the moment. Four years later, she’s hearing more students and teachers take risks in their dialogue about racism and politics.

“I think it’s going in the right direction,” she said. “There’s been a lot of supports for how to talk about difficult topics in the classroom.”

— Laura Faith Kebede

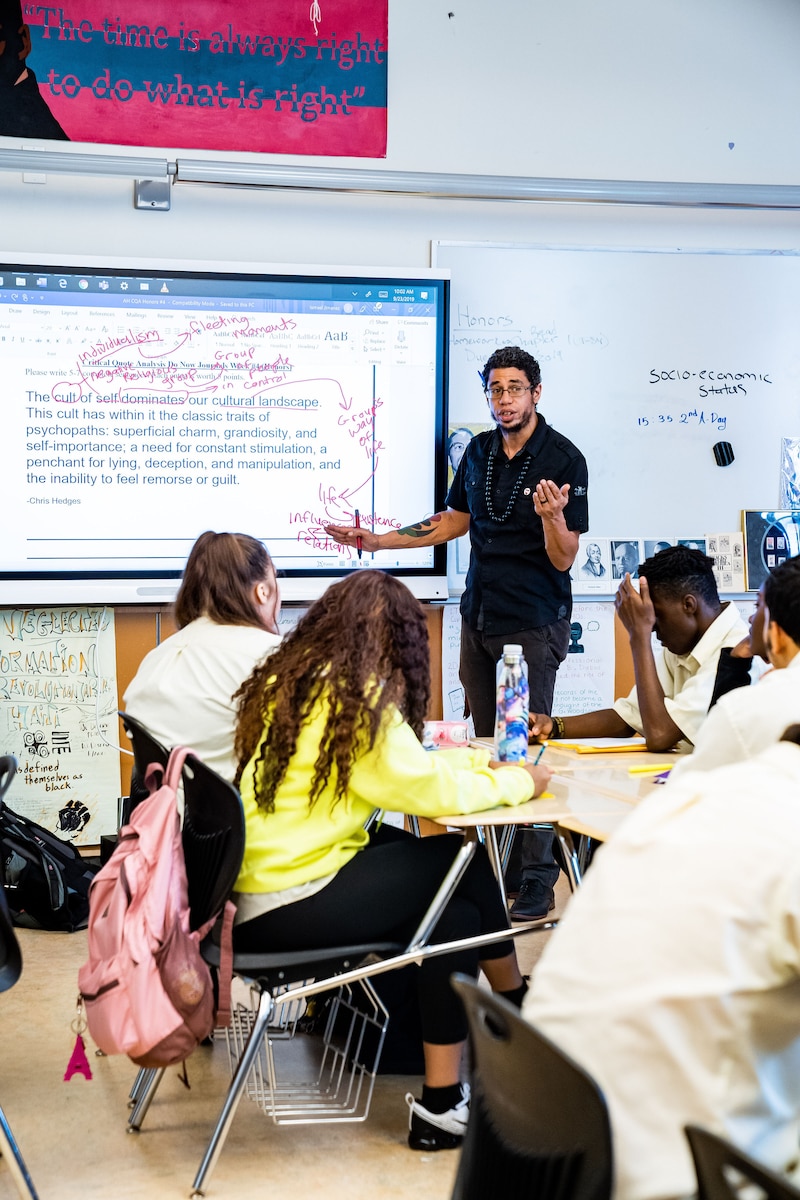

Ismael Jimenez, a history teacher at Kensington Creative and Performing Arts High School in lower Northeast Philadelphia, makes it a habit to speak to his students every day about current and political affairs.

On Wednesday those topics were front and center as officials were still tabulating results from Pennsylvania in Tuesday’s presidential election, votes that could give a decisive edge to Trump or Biden.

“For the election I definitely made sure to talk to my students the day after,” Jimenez said. “And quite possibly we won’t know until Friday on the results.”

Jimenez’s class expressed a mix of apprehensive and some relief. Students were concerned about Trump’s announcement early Wednesday morning that he had won the election before all votes were counted. The high school is 95 percent Black and Latino, according to Jimenez. “They think it’s stupid what Donald Trump is saying about him winning the race.”

But students were relieved by the lack of unrest as the election outcome hung in the balance. Local officials had boarded up walls throughout the city, anticipating protests similar to those following the police killing of Walter Wallace.

“It’s really interesting because I’ve never had students this knowledgeable about the Electoral College and how that process works,” Jimenez said.

“As a high school teacher I get 10th and 11th graders who have never been asked to think critically about the world in a certain kind of way,” Jimenez said. “These discussions help to change that.”

— Johann Calhoun

Heike Domine’s sixth grade social studies class was ready for Election Day.

They had studied the history of voting rights in the United States, from the disenfranchisement of Black people to modern forms of voter suppression. They’d held a mock election in which Joe Biden enjoyed the type of blowout that eluded him Tuesday. And they had been cautioned not to expect a quick resolution of the divisive presidential race.

“The election isn’t straightforward like 2016’s,” said Hafsah Dauda, one of Domine’s students at TEAM Academy charter school in Newark. “We have to wait for all the mail-in ballots to go in to see who’s president.”

Still, on Wednesday, the students were anxious to know the results. After all, there’s a lot riding on the election’s outcome. Hafsah was concerned about low-income Americans, especially essential workers, and believed that a Biden presidency could raise their wages.

Student Abdul Haq-Adome was thinking about how to repair the U.S. economy and safely reopen businesses and schools such as his own, which he hasn’t been able to enter since March. Abdul had read that President Trump didn’t have a clear plan for managing the pandemic, which didn’t exactly fill Abdul with confidence.

“I’m really hoping that, whichever person is picked to be the president,” he said, “that instead of just sitting there and hoping COVID-19 will eventually go away, they will actually have a plan to fight the virus.”

Before the election, some of Domine’s students had questioned whether voting really matters. Domine responded that it’s understandable why some people grow frustrated with the political system, especially Black Americans, who have never had to stop fighting for their rights. Yet, she said, people who withdraw from the democratic process “lose their opportunity to share their voice.”

That rang true to Hafsah, whose father voted in the election.

“He felt like it’s an important part of his life to vote because he thinks it might change the whole society,” she said. “If you don’t vote, that means that you’re not speaking for yourself.”

Abdul agreed.

“It could be your one vote that decides who’s going to be the President of the United States,” he said.

His classmates appear to share his conviction about the importance of voting. Domine hadn’t been sure how many of her sixth graders would participate in the mock election, which was held on a day when students didn’t have class. To her delight, 112 of the 115 students cast ballots on their day off.

“To me, it spoke to the fact that the kids took it to heart,” she said, “that they have to ask for a seat at the table.”

— Patrick Wall

“You have to know where you came from in order to know where you are going,” charged Angela Crawford, an English teacher at Martin Luther King High School, to a student at 9:30 a.m. before closing her first period class on Wednesday.

Crawford is an English teacher who makes it her mission to discuss current events with students. So it may not come as a surprise that this week’s topic for Crawford’s second period class was the aftermath of Tuesday’s presidential race between Trump and Biden.

The student population at MLK is majority Black and sits in the West Oak Lane section of Philadelphia.

“I don’t shy away from uncomfortable conversations. I don’t push away. I teach English but it’s from a very Black perspective,” Crawford said before opening her Zoom class to the three seniors.

Students were not shy about how they felt. “In my opinion there’s very little the president got right for me as a Black woman or anyone who is a person of color,” said one student, Phoenix James. “Throughout his time in office and his campaign Trump was supporting white supremacy. Calling Black Lives Matter and LGBTQ groups bad and calling them terrorists was not good.”

Jazmyn Ervin argued she didn’t feel like she understood what Biden stands for. “I didn’t like Biden too much either, because I don’t know him like I do Trump. Even though he spent time in office I really don’t know who he was while he was in office. Like, is he going to be like Obama? Or will he be completely different once he gets into office?”

Bre’niyah Gibson, who voted for the first time this year, told the class that discussions like this one felt more relevant to her than usual schoolwork. “There are so many things we learn at school that don’t benefit us at all. Stuff that we learn has nothing to do with what we need to know before adulthood.”

At the conclusion of her Zoom class, Crawford said she’s concerned how the students are handling the recent uprisings and incidents such as the Walter Wallace police shooting in West Philadelphia.

“What is prominent in these students’ thoughts?” she wondered. “I want them to understand their voice has value.”

-Johann Calhoun

Maddy Alvarado’s students wanted to know how she had voted in the previous day’s election.

“As a teacher, you’re supposed to have this neutral ground that you stand on, or you don’t necessarily share too much of your opinion, or you give both sides of it, you know?” said Alvarado, a fourth grade teacher at Westlake Elementary School in Indianapolis. “So I’m over here like, ‘I don’t think I can tell you.’”

Although she avoided sharing her political views with the class, she decided to devote that day’s social-emotional learning time to talking about the presidential election.

Even though her students won’t be old enough to vote for nearly a decade, many of them have strong feelings about the candidates and what’s at stake in 2020. As Alvarado walked around passing out breakfast, her fourth graders talked among themselves about the candidates. Some expressed concern over the Trump administration’s policy of separating parents and children who come to the United States seeking asylum.

Throughout the morning, the children opened up about what was on their minds — including fears that some of the votes cast wouldn’t be counted — and Alvarado acknowledged what remained unknown. By Wednesday morning with several swing states still in play, who had won was an open question.

“It’s still being counted,” she said. “So this is going to be a week-long discussion.”

-Aaricka Washington

Elizabeth Milligan Cordova’s civics students were not expecting to know the outcome of the presidential election Wednesday morning.

“This time, I knew it wasn’t going to be a one-day affair,” said Milligan Cordova, a high school social studies teacher at Denver’s Northeast Early College.

Milligan Cordova, who is in her 12th year of teaching, had to prepare herself as well as her students for the likelihood of an extended process with no immediate answers.

“In 2016, I was so just in my own feelings about the election that it was difficult to teach,” Milligan Cordova said. “This election I knew I had to prepare myself first.”

That meant getting into a mindset, she said — being ready for anything. But, she said, she’s also changed her past views on trying to be objective.

“As though there’s any such thing,” she said. For her students, not being transparent is an act of violence, she said.

“I don’t tell them what I think is right about taxation or size of government or other governmental policies,” Milligan Cordova said. “But to say I’m going to be mysterious about my vote is to say maybe I’m voting for someone who has dehumanized you.”

On Wednesday, she allowed time for students first to share their feelings. More than 9 in 10 students in her school are students of color. Many said they were anxious about violence following the election.

One student, Dalahna Cordova, 16, said she has felt targeted recently as a member of the LGBT community. In another class, she is working on a project to educate the school on how to support fellow LGBT students following the election.

“It’s just a really scary time,” said the student, who is not related to her teacher. But, she added, her school and teachers like Milligan Cordova have helped her keep calm and understand what is happening this week.

Milligan Cordova closed out her civics class Wednesday asking students to take what they’ve learned about the electoral college, and look at the percentage of votes counted, to make predictions about eight states and the outcome of the presidential election.

“We’ll look at the results and how they’ve changed,” she said. “And we’ll just have to wait and see how things unfold.”

— Yesenia Robles