Are schools sitting on their CARES Act cash? Randy Russell, the superintendent of a small school district outside of Spokane, Washington, laughed when asked.

“I don’t know anybody that is,” he said. “Most everybody needed things right away to support the kids.” His district’s $58,000 in federal relief money has already gone to the kind of expenses that 2020 has made normal: Chromebooks, masks, and delivering food to students while school buildings were closed.

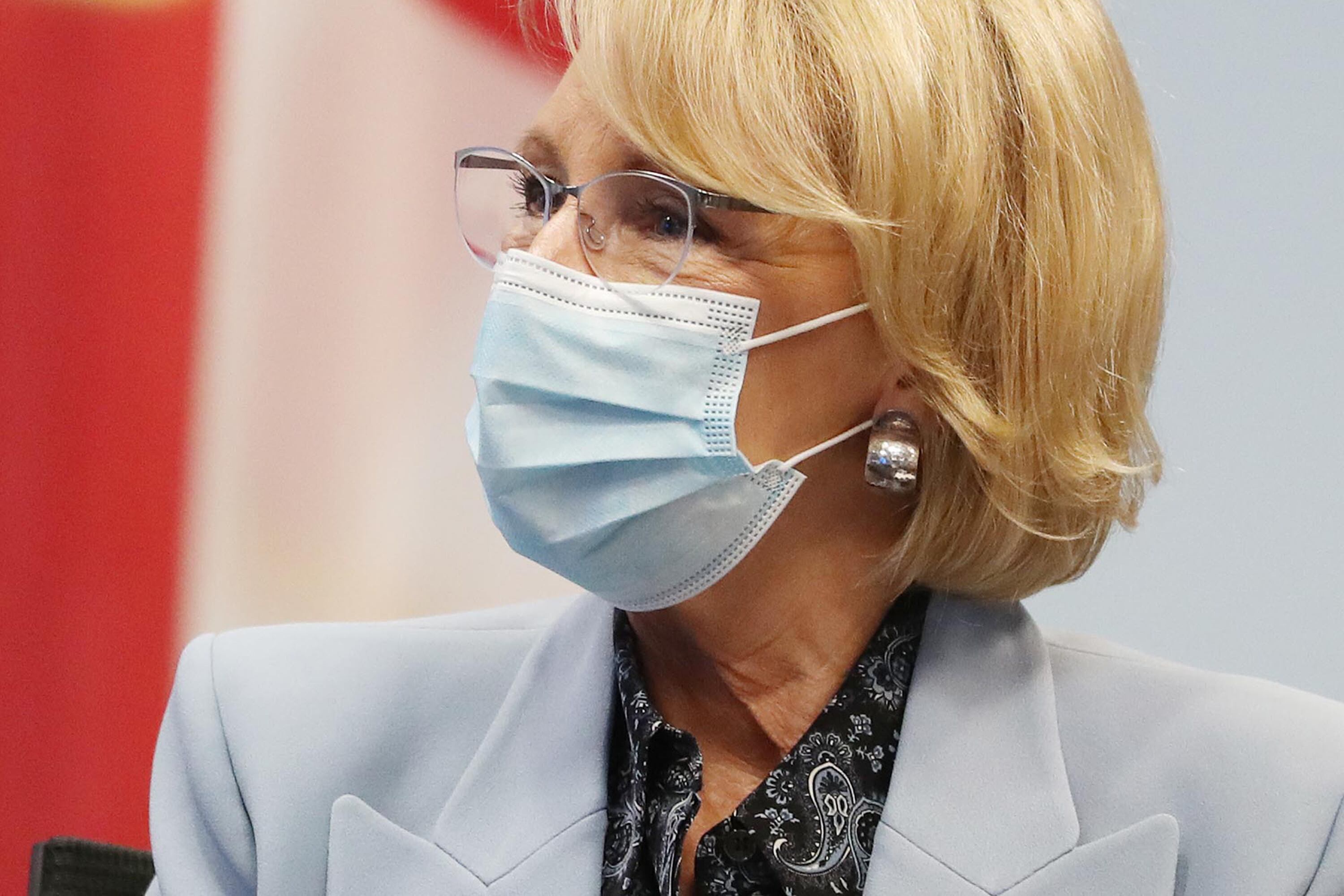

The question of how much coronavirus relief money schools are spending, though, has become politically fraught. Last month Education Secretary Betsy DeVos claimed that schools have left billions unspent while many school buildings remained closed.

Schools, “while complaining about a lack of resources, have left significant sums of money sitting in the bank,” she said in a statement sent to reporters across the country.

But the data DeVos is relying on is incomplete and misleading, according to state and local leaders. Her comments, though, are the latest articulation of a belief that has animated her tenure: school districts are wasteful and ineffective, so spending more money to help them improve is unlikely to work. As Congress debates its next move, the remarks are also a parting shot at advocates who say students and schools need federal funds to fully recover from the pandemic’s disruption.

“Trotting out the narrative that schools aren’t spending this money builds the case for schools not requiring more stimulus dollars,” said Jess Gartner, CEO of Allovue, a company that works with districts to improve their school finance systems.

DeVos rests her claim that schools are stockpiling cash on a database that her department published in November. It shows what share of CARES Act dollars have been drawn down from the U.S. Treasury by each state. Of the $13.2 billion earmarked for K-12 schools, just 12% had been reported as spent by the end of September.

Broward County schools, the country’s sixth-largest district, illustrates what this data misses. Broward received $44 million in CARES funding, and Judith Marte, its chief financial officer, says the district has appropriated some $30 million, and plans to use the remainder to make up for likely declines in tax revenue. But DeVos’ database would only capture $7 million of that.

Why? Those records only reflect bills that have already been paid and processed. Broward, for example, has contracted for $6 million in extra nursing services, Marte said, but since the district hasn’t been billed yet, the funds haven’t been drawn down.

The federal database reports that less than 5% of Florida’s K-12 CARES money has been drawn down.

“I understand from [DeVos’] seat it looks the money may not be being drawn down as fast as she may think it should be, but that doesn’t mean the money isn’t being spent,” Marte said. “I certainly am not sitting on a lot of CARES money, and I know my colleagues I speak to across the state of Florida are not as well.”

The database would also miss salaries of extra teachers or other staff hired to help schools with social distancing or facilitate hybrid instruction, noted Jonas Zuckerman, the president of the National Association of ESEA State Program Administrators. Since districts pay salaries over the course of the year, DeVos’ database would only account for a fraction of those costs.

There are other reasons the portal provides an incomplete picture, including more banal realities: the process of getting money to schools often includes delays, as does the process for that money being reported as spent by the federal government.

“There’s a lot of steps that happen prior to the money being drawn from the U.S. Treasury,” Zuckerman said. “It being distributed to states, then distributed to school districts, then once the school districts have the money the school districts budget those funds, they spend those funds, they submit a claim to the state, the state submits a claim to the U.S. Department of Education.”

Each step in that process takes time, and only at the very end is the money counted as drawn down. But schools are still using — or counting on using — that federal money before that process is complete.

Marte also noted that some districts, fearing budget cuts, may wait to seek reimbursement until the end of the year when they will have a clearer picture of their finances. And at least in two states, New York and Texas, schools have already seen most CARES dollars effectively wiped away in the form of state budget cuts.

A spokesperson for DeVos did not directly respond to questions about limitations of the data that the department published and promoted. “All of this is an attempt to distract from the fact that a great deal of emergency funding remains available to help schools reopen safely,” Angela Morabito said in a statement.

Ultimately, though, it’s not clear exactly how much CARES Act money schools have budgeted and how much is still available. “It’s too early in the process to actually have a sense of what that number actually is,” said Zuckerman whose organization sent DeVos a letter criticizing the department’s database as inaccurate. “We just don’t know it yet.”

Debates about how much additional federal aid schools need are continuing. Over the summer, some of the school reopening debate focused on whether schools would have the resources they need to open buildings. This fall, though, districts that haven’t reopened have cited rising COVID cases and the reluctance of many parents and teachers to return.

That may be in part because school budgets have not been hurt nearly as badly as some feared by the pandemic.

On the other hand, in the absence of additional federal relief, states are likely to cut school budgets next year. School leaders also say they need more money and more staff to help students who have fallen behind after months of disrupted schooling.

“We would love to be able to tell you that we were able to hire additional staff,” said Russell, the Washington superintendent. “Unfortunately, given our financial situation, we have not been able to do that.”