It was a cold and sunny Boston day two weeks ago. I was out of town, visiting a neighborhood charter school full of Black and brown students and white, well-meaning teachers. The clock read 2:42 p.m., and one of those well-meaning white teachers stood in front of us and began:

“So, let me start by saying I’m so nervous because this is really exciting for me, and I am so honored to be the chair of the Black Lives Matters week for Black History Month. … We want to invite successful black people that we know to talk to our students … They don’t have to be President Obama or Beyoncé or anything like that; they can be anybody. We just want our students to see really good, really successful black people.”

All I could think to myself was, here we go again – the shortest month of the year has made its journey around the sun for another round of exoticisms, romanticisms, and activities in honor of what some affectionately call, and others of us exhaustingly call Black History Month.

The seed for Black History Month was planted by the noted scholar Carter G. Woodson, the son of former slaves and a Ph.D. graduate of Harvard University, where his work privileged the socio-cultural impact of Black folks. In 1926, he declared the second week of February Negro History Week, arguing, “If a race has no history, if it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world.”

What was a week is now an entire month, which some see as a powerful recognition of Black narratives and others see as an illusion of advancements in race relations. Regardless of where you are on that continuum, we educators have the responsibility (and burden) of ensuring that our rhetoric prioritizes the truths of Black identity in a nation plagued by “alternative facts.”

The question, then, is how do well-meaning white teachers — and some black educators who have internalized racism — reimagine their rhetoric during Black History Month? Here are three strategies, which are the result of observing educators struggle to navigate the expectations of many schools during Black History Month. These strategies are not meant to be a panacea, but a beginning of a larger conversation on how to serve all students better, particularly our Black and brown students.

- Talk about systemic racism, not only personal agency.

When we neglect our responsibility to talk about how racism is embedded within the fabric of social and political structures – education, criminal justice, employment, income, housing, and healthcare – we unintentionally permit our students to presume that “really good, really successful” Black folks are exempt from the impact of racist structures. But we can resist the white supremacist influence by acknowledging that even those we proclaim as notable — King, X, Morrison, Hughes, Ali, Angelou, Baldwin, Franklin, Winfrey, Obama, and Knowles-Carter — existed or exist within a racist system despite their diligence, effort, aptitude, and charisma.

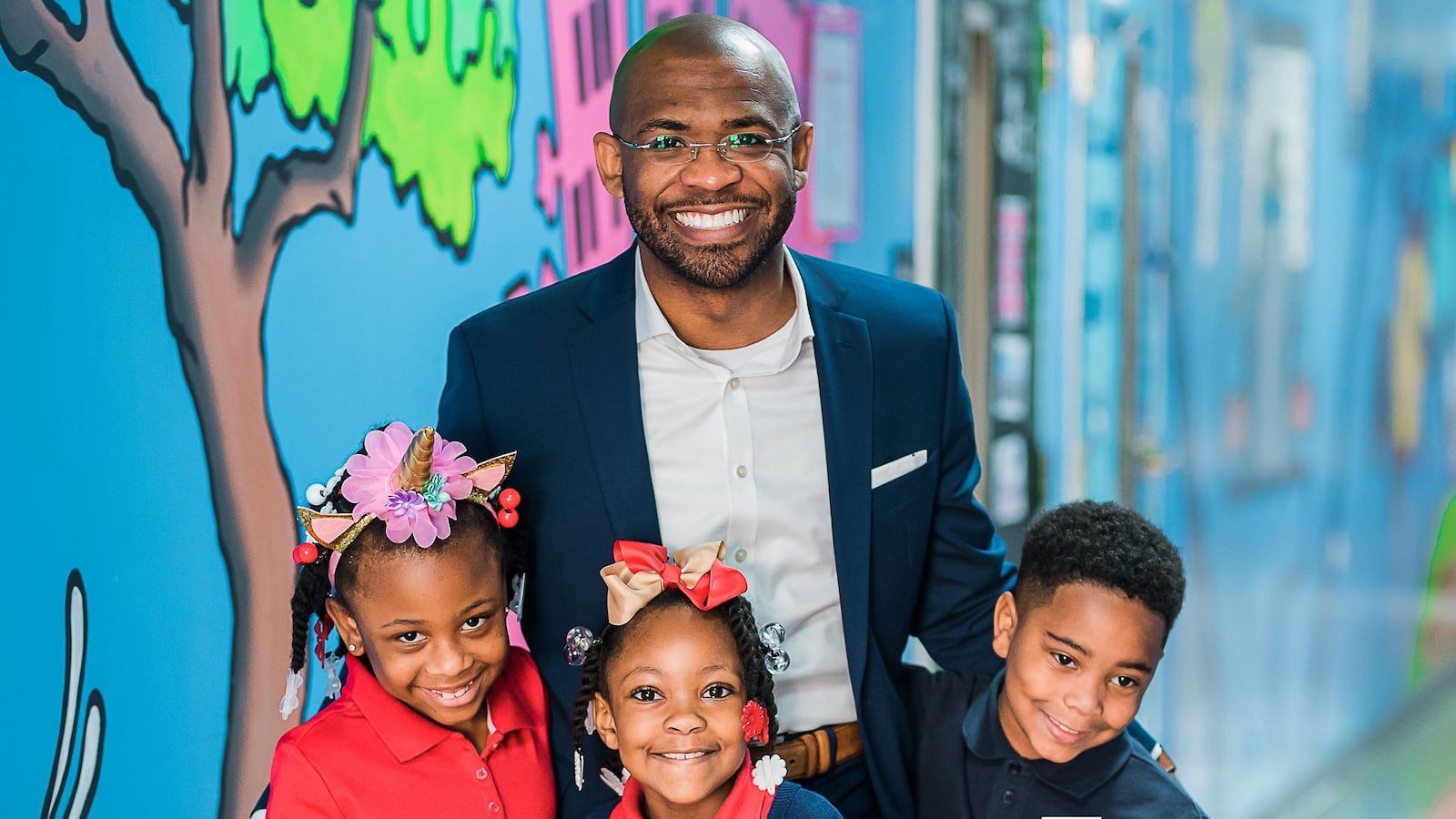

It is unjust to focus on the personal agency of our students without naming that they exist in a system designed to dismantle their efforts and smarts. As a black educator who completed a doctorate, attended an Ivy League school, and is now leading a network of schools, it is easy for my well-meaning white colleagues to attempt to lift my narrative up as an example of personal agency overcoming systemic racism. However, I continue to navigate this system, and I need my colleagues to understand that.

Once, several well-meaning white teachers were waiting to receive feedback on their Black history lessons from me, their recently onboarded and unapologetically Black dean. One of the teachers whom I had yet to meet handed me her lesson, titled, “Education: The Great Equalizer.” I paused, not knowing the degree to which I should unpack the problem of her lesson’s framing. “Who exactly does education equalize?” I ask. All of us, she told me. I responded, “Does it really?” “Yes … I think so,” she replied, her face reddening. “With a good education, we can all make it in America. Look at you, look at me.”

On the job only two weeks and the only black staff member outside of the dining hall, I took the safest route in response and encouraged her to reflect on the inequalities and inequities embedded in American education — from funding to facilities.

- Talk about history in the context of today.

We know that it is called Black History Month, but all history must be placed in today’s context if our objective is to ensure its relevance. Because what is it to have freshly delivered food in a refrigerated truck because of Frederick McKinley Jones’ ingenuity without discussing Trump-era cuts to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, effectively sustaining food deserts — areas without easy access to fresh foods — in low-income urban and rural communities? What is to know the first successful pericardium surgery was performed by Daniel Hale Williams without talk of persistent racial disparities in healthcare? What is it to be moved by Dr. Martin Luther King’s dream for economic equality without talk of the widening racial wealth gap between Black and white folks?

History is not only insight into what has been, but also a catalyst for reimagining what can be.

I recall teaching a fifth-grade class where I introduced Garrett Morgan’s three-light traffic-light system. One of my most rambunctious, yet immensely thoughtful, students blurted, “Who cares, Mr. Harvey? That was a hundred years ago.” I asked if he liked sitting in traffic. “No!” he responded. “Show of hands! Who likes car accidents?” The entire class laughed, grunted, and almost collectively responded, “Nobody likes accidents!”

“Could you imagine only having a two-light system of ‘go’ and ‘stop’?” I asked them. No, one student replied. “We need the yellow light because it not only tells cars to slow down, but it tells people walking and riding bikes that they only have a few seconds like to get across the street,” he said. “Garrett Morgan didn’t just help traffic and car accidents, Mr. Harvey, he saved the lives of walkers and bike riders.” At that moment, a warmth overtook me — a lesser-known icon of Black history found contemporary relevance with 10-year-olds.

- Talk about navigating and disrupting oppression.

Harvard professor Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham coined the phrase politics of respectability to describe when racially marginalized groups attempt to distance themselves from the stereotypical aspects of their communities in order to fit white supremacist standards. The underlying assumption is that respectability will position Black folks to increase their proximity to privilege and access those “inalienable rights” America’s founders promised.

As a result, I’ve seen some teachers overemphasize rhetoric that tells our Black and brown students to “pull those pants up so you look professional,” or “stand straight, arms to the side, eyes in front of you, feet together, and lips sealed” as if silence, stillness, and prison-position is an indication of potential attainment. This reinforces a mindset of navigating oppression without providing them opportunities to disrupt what they are navigating.

This month gives teachers an opportunity to change their rhetoric and lead students in creating disruptive words and disruptive writing norms and disruptive dress codes. For example, I’ve explained to my students that I spell my name “rob” — with a lowercase R — because, as an educator, I choose to “reimagine the recommended relationship between capitalization and proper nouns because all constructed knowledge should be deconstructed.” As teachers play clips of Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech or discuss the accomplishments of notable Black influencers, they must not forget that their breaking norms, ignoring the rules, and reimagining culture are why we have this month in the first place.

The language around Black History Month, especially the language used by white educators, needs to stop its bend toward safeness. It needs to bend the arc of its language, voice, and power toward justice, and toward complex truths of Black folks in a white nation. As educators, a commitment to love and justice means using our voices – our influence and our power – to change the rhetoric of Black past, Black present, and Black future.

Dr. Robert S. Harvey is the superintendent and senior managing director of East Harlem Scholars Academies, a network of public charter schools in New York City. He also serves as an adjunct professor with teaching interests in race, religion, education, and leadership. Dr. Harvey is the author of a forthcoming children’s novel, “I Already Know,” expected spring 2020.

About our First Person series:

First Person is where Chalkbeat features personal essays by educators, students, parents, and others trying to improve public education. Read our submission guidelines here.