When Andom Ghebreghiorgis was a middle school teacher at the Richard R. Green campus in the Bronx, his students sometimes arrived to class late, reeling from being stopped by the police on their way to school.

“They would enter the classroom very agitated, and not really in a place to learn,” said Ghebreghiorgis, who taught there a decade ago. “On the days in which my students were stopped and frisked, their whole day was affected.”

He added, “It probably still affects them now.”

A recent study offers tangible support for Ghebreghiorgis and other critics of stop-and-frisk: Ratcheting up this policing tactic led more New York City public middle school students to later drop out of high school and fewer to enroll in college, it found. The harmful effects were particularly large for black students — who also bore the brunt of stop-and-frisk.

The study, conducted by Andrew Bacher-Hicks and Elijah de la Campa, both doctoral students at Harvard, focuses on New York City middle schools between 2006 and 2012, a period when stop-and-frisk substantially increased.

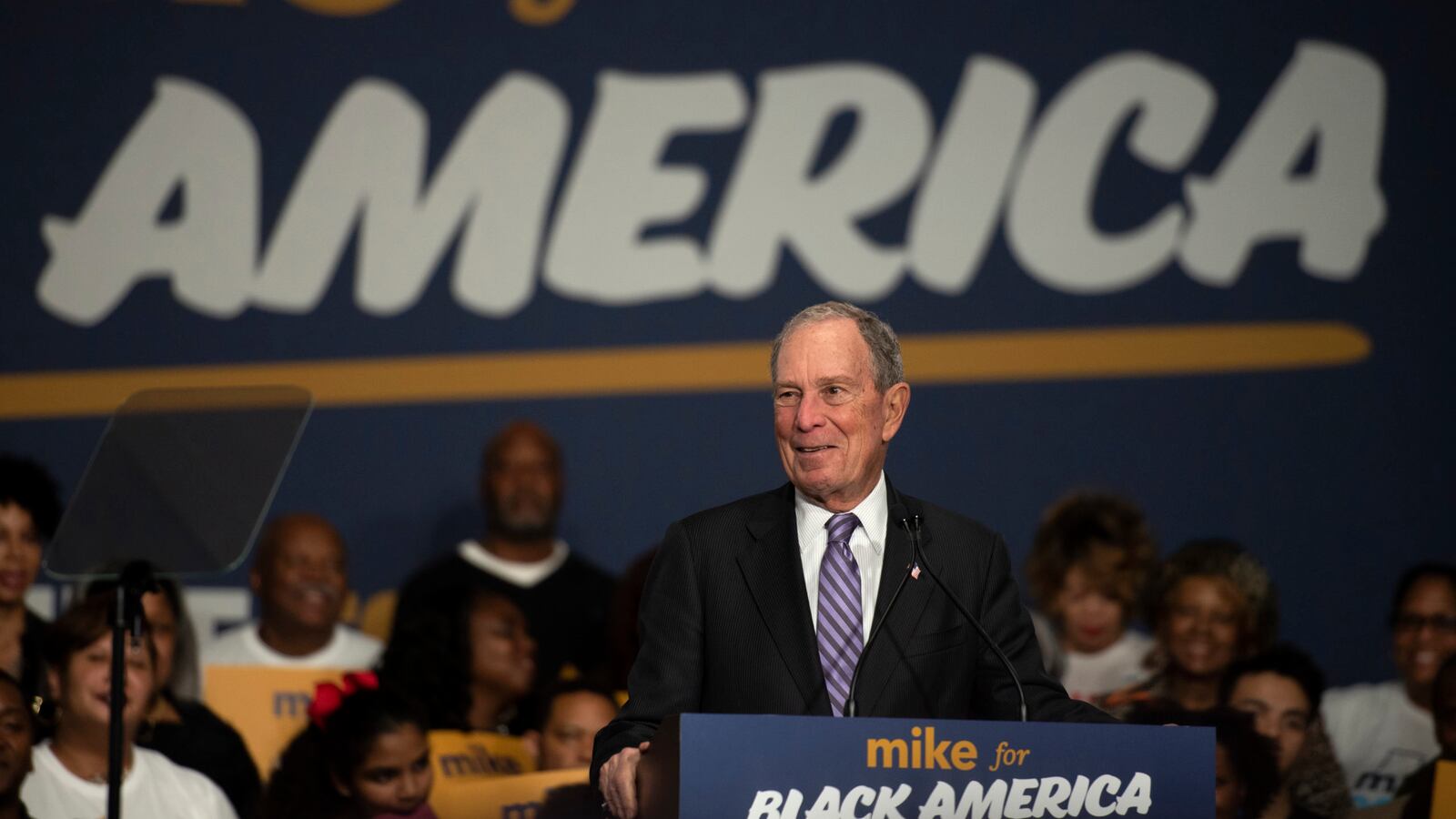

The findings come as former New York City mayor Mike Bloomberg, now vying for the Democratic presidential nomination, is rising in the polls but facing backlash for rapidly expanding — and repeatedly defending — the controversial police tactic, which a judge ruled was racially discriminatory in 2013. (Bloomberg Philanthropies is a funder of Chalkbeat.)

Bloomberg now apologizes for the policy, and points to his record on education as a way of boosting his bona fides with voters of color. But the latest study illustrates how stop-and-frisk often spilled over into New York City’s classrooms during Bloomberg’s time as mayor, harming the students he says his education policies were meant to help.

The study’s findings also are relevant for districts around the country that are ratcheting up police presence in response to safety concerns.

“We should be careful when we think of policing or other types of disciplinary approaches that are meant to reduce crime or improve discipline but [are] also clearly having effects on social and educational outcomes,” said Bacher-Hicks. “This should make policymakers think twice about unequal effects of these policies.”

Stop-and-frisk hurt black middle school students

To tease out cause-and-effect, the researchers took advantage of the fact that some NYPD precinct commanders directed officers to conduct more (or fewer) stops. The study examined what happened to middle school students when commanders with different stop-and-frisk patterns moved into a local precinct. The idea was that this move — and its effect on stops — was as good as random. (The researchers couldn’t simply look at the prevalence of stops directly because this was likely influenced by many other factors that could also affect students’ educational outcomes.)

In the short run, the tactic led to notable upticks in school absence rates, particularly for black students, who were 1.4 percentage points more likely to be chronically absent from school in areas with substantially more stops.

That didn’t surprise Christian Reyes, who was stopped by the police multiple times when he attended The Equity Project Charter School, an Upper Manhattan middle school.

The first time, he was on a school break and was stopped by a police officer who demanded to know why he wasn’t in school. “I was just like, ‘Oh my God, I’m in trouble with the law. I’m going to get locked up or I’m going to get in trouble now,’” recalls Reyes, who is Hispanic. “I just panicked.”

Reyes, now a senior at Manhattan’s Beacon High School, said the experience didn’t make him avoid school. But he understands why it might make other students less engaged. After his encounters with police, he was constantly looking over his shoulder.

“Students will take those negative thoughts and bring themselves down,” Reyes said.

The researchers also tracked students into high school and beyond. Overall, those exposed to more stops in middle school were about half a percentage point less likely to graduate high school and 1 point less likely to enroll in college.

The effects were largest for black students: they were 1.8 points less likely to graduate and 2.5 points less likely to enroll in college. Perhaps surprisingly, the effect was similar for black boys and black girls, even though black boys were much more likely to be stopped. This suggests that the consequences may come not just from being stopped, but from the environment created by frequent police interaction.

There were no clear effects for Hispanic students. For white students — who make up about 15% of New York City public school students — there was some evidence that stop-and-frisk actually led to slightly higher graduation rates. It’s not clear why.

The study also finds that stop-and-frisk led to fewer disciplinary incidents in schools. Despite this, in schools with a large number of black students, students reported feeling less safe. (A separate paper by the same researchers found that stop-and-frisk rates had no effect on felony crime.)

Perceived benefits for white residents may have been one of the political reasons stop-and-frisk was kept in place for so long, even as the policy was harming New York City students overall.

“While police stops could — in theory — reduce inequality by improving safety in high-risk schools and communities, we show that a reliance on this form of proactive policing increases racial inequality across a range of long-run educational outcomes,” conclude Bacher-Hicks and de la Campa.

Prior research supports the new findings

Joscha Legewie, a Harvard sociology professor, has conducted separate research illustrating a similar phenomenon: increased police presence near New York City middle schools led to lower test scores among black male students. He praised the latest research as “innovative and convincing.”

“We now have two articles based on very different methods and assumptions showing the same pattern,” he said.

Other research in Texas has found that security officers in schools can lead to declines in high school graduation and college attendance.

Carla Shedd, a sociologist at the CUNY Graduate Center, has studied how stop-and-frisk affected high school students in Chicago. She raised concerns about the fact that the new paper, for methodological reasons, looks only at middle school students, rather than high schoolers.

But Shedd’s work also offers a potential explanation for the far-reaching nature of the latest findings. For students, she said, the impact of police presence is “not necessarily a direct sense of ‘I’m being arrested,’ but ‘I am being scrutinized, I am being held to a higher standard.’”

“Those are things that can lead to estrangement and kids having lower achievement,” she said.

Ghebreghiorgis, the former teacher who is now running for Congress, said the police were a frequent presence at the school, often positioning themselves outside during dismissal.

“We had a lot of stories of unjust encounters with the police. It affected everyone — teachers and students as well,” said Ghebreghiorgis, who is black.

Bloomberg has backed away from stop-and-frisk but promoted his education record

Bloomberg’s reliance on stop-and-frisk has recently made headlines after audio from 2015 surfaced capturing the presidential hopeful using racist language defending the practice even after it was found to be discriminatory by a judge and had been scaled back.

“Ninety-five percent of murders, murderers and murder victims fit one M.O.,” he said. “You can just take a description, Xerox it, and pass it out to all the cops.”

Bloomberg walked back his support of the practice shortly before entering the presidential race. On the campaign trail, he has leaned into his record as head of the country’s largest school system, which he successfully pushed to bring under mayoral control.

“This issue and my comments about it do not reflect my commitment to criminal justice reform and racial equity,” said Bloomberg in a statement last week. “We overhauled a school system that had been neglecting and underfunding schools in Black and Latino communities for too long.”

He apologized again at a campaign rally in Houston last week, in which he focused on appealing to black voters.

The Bloomberg campaign did not respond to a request for comment on this story.

As mayor, Bloomberg implemented a number of controversial school reforms, including the closing of a number of large high schools, the tightening of teacher tenure rules, and the expansion of charter schools. Research has found some of these changes — including high school closures and creation of new small schools — contributed to improved outcomes, including the city’s rising graduation rates. Between 2005 and 2013, the graduation rate for New York City’s black students rose by more than 20 percentage points.

The latest study, though, suggests that these gains would have been even greater if not for stop-and-frisk — and highlights how Bloomberg’s record on schools and his record on criminal justice are connected.

“These worlds cannot be divided. In fact, they overlap,” said Shedd, the CUNY professor. “Students are the ones who feel the intersection.”

Want more? Here’s a deeper look at Michael Bloomberg’s education legacy. Find the latest on his proposals – as well as what other Democratic presidential candidates have said about education – in our 2020 tracker.