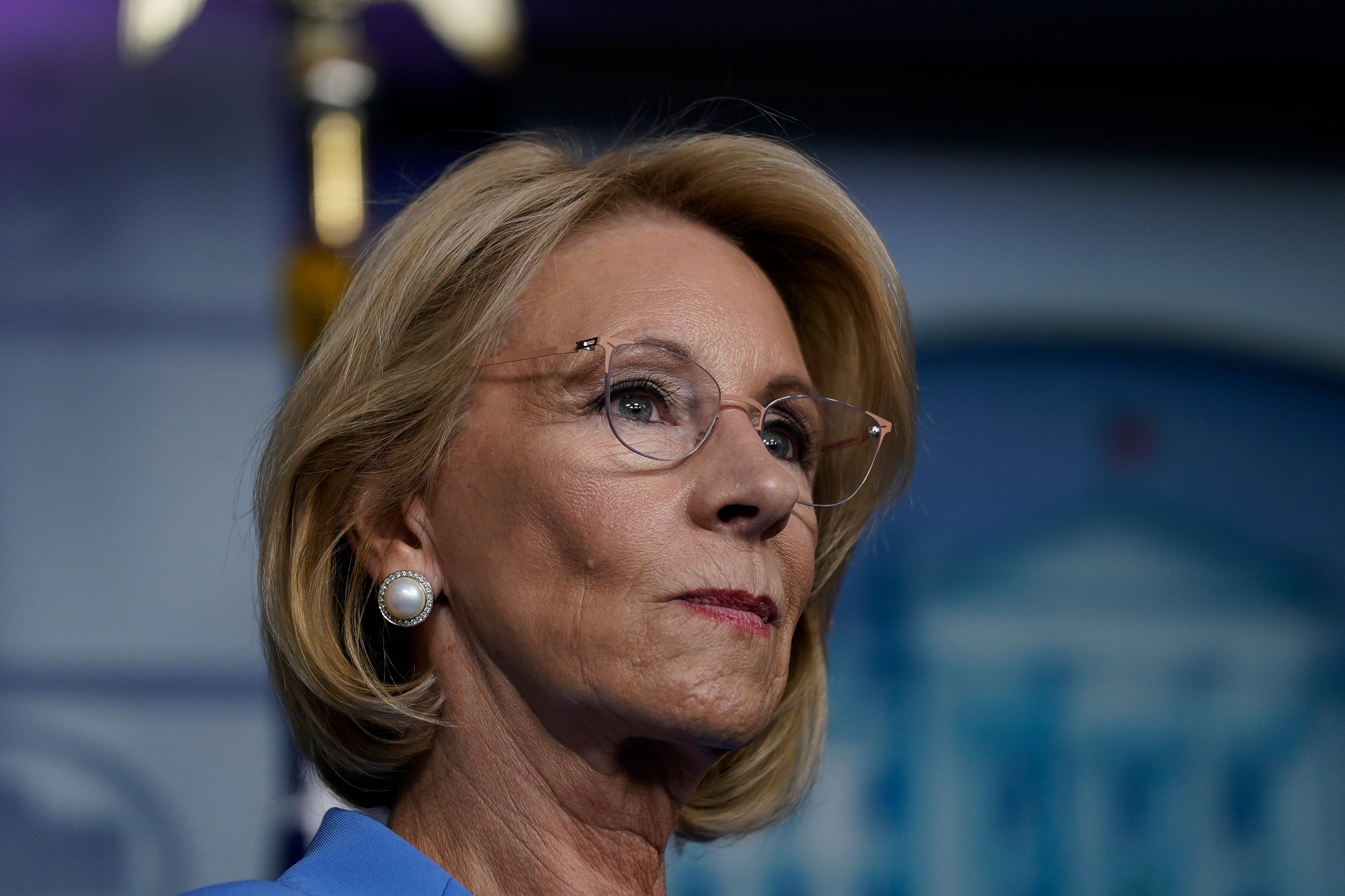

Education Secretary Betsy DeVos won’t recommend giving school districts the option to bypass major parts of federal special education law, the department announced Monday.

The move will be celebrated by disability rights advocates, who had feared that giving districts any wiggle room could pave the way for a more permanent undoing of civil rights for the country’s nearly 7 million students with disabilities.

It also largely conforms with how DeVos has handled the fallout of the coronavirus pandemic so far: by telling school districts that the obstacles they face are surmountable through hard work and innovation.

But it also leaves big questions about compliance and whether school districts will become vulnerable to legal action if they fail to fully serve students with disabilities, now that nearly every state has ordered or recommended that school buildings remain closed for the rest of the academic year.

“While the Department has provided extensive flexibility to help schools transition, there is no reason for Congress to waive any provision designed to keep students learning,” DeVos said in a statement. “With ingenuity, innovation, and grit, I know this nation’s educators and schools can continue to faithfully educate every one of its students.”

Under a provision of the coronavirus relief package that passed at the end of March, DeVos had until Monday to recommend any additional waivers of federal education law to Congress. Already, states have been able to apply for waivers to skip annual tests and change how they spend certain federal education dollars.

In her report, DeVos did not recommend any waivers of the core tenets of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, the main federal special education law.

DeVos did recommend two minor special education-related waivers. One would allow schools to continue providing toddlers with disabilities services they had already received past their third birthday, when they would usually need to be reassessed. The other concerns grants to special education teachers.

This issue became a flashpoint as school buildings began closing due to the coronavirus pandemic, as it became clear just how many students with disabilities would lose access to specific types of support they received in school — whether that was a therapy that required an adult to physically touch a student or a one-on-one aide to help a student with math assignments.

Many schools are trying their best, advocates say, and some districts that got an early start distributing devices also began providing many services by phone and video soon after their buildings closed.

Still, students across the country are going without.

“They’ve pretty much just gone hands off,” one Michigan parent of a student with a disability said in early April of her child’s school. “We have kiddos that are regressing, and there’s nothing in place.”

Two prominent groups of special education administrators had requested “temporary and targeted” waivers that would give schools more time to comply with requirements for evaluating students, reviewing special education plans, known formally as Individual Education Programs, and responding to parent complaints.

“Without flexibility, we will generate endless cycles of reporting about how COVID-19 caused money to be unspent, evaluations to be delayed, and services and supports that are in IEPs that are not able to be implemented,” the two groups said in a letter to top-ranking members of Congressional education committees.

A national group representing superintendents had favored more sweeping waivers that would consider schools to be in compliance with IDEA “unless they are intentionally discriminatory or demonstrate bad faith or gross misjudgment.” And some superintendents had said they supported the idea of a waiver that would hold schools harmless and protect them from possible costly lawsuits.

“What happens four months from now, when we’re back in school and back into a routine, and lawyers are hungry?” the superintendent of one small rural district told the New York Times. “That empathy that exists for teachers right now, that could evaporate.”

But many disability rights advocates had strongly opposed offering any kind of special education waivers, arguing it had never been done in the 45-year history of the law. They said schools should work directly with parents to extend timelines and amend special education plans. They worried that if schools stopped providing some services now, it would cause students to fall farther behind, and make it even harder to make up missed services later.

“There is a lot of flexibility already in IDEA,” said Wendy Tucker, the senior director of policy for the National Center for Special Education in Charter Schools, who is also the parent of a child with a disability. “There’s a lot of ways to address some of the things that fall far short of actually walking back civil rights.”