Jose Muñiz has done everything he can think of to get ready to take his Advanced Placement Calculus AB exam from home on Tuesday.

The 18-year-old senior at Back of the Yards College Prep in Chicago chose a method for answering questions: writing by hand on graph paper, then taking and sending photos with his phone, an option that seemed easier and faster than typing symbols and equations in a Google Doc.

He wrote up a “cheat sheet” of formulas, since the exam will be open notes this year. And he’s asked his mother and younger sister to turn off their devices that use Wi-Fi during his exam, since their home internet can slow down when multiple people use it.

He’s also practiced uploading photos to the demo site meant to help millions of AP students feel comfortable submitting their work from home. But that didn’t go quite as smoothly as Muñiz had hoped.

“It kicked me out of the website, which is something I freaked out about. Like, what if this happens during the exam?” Muñiz said. “It’s something new to everyone.”

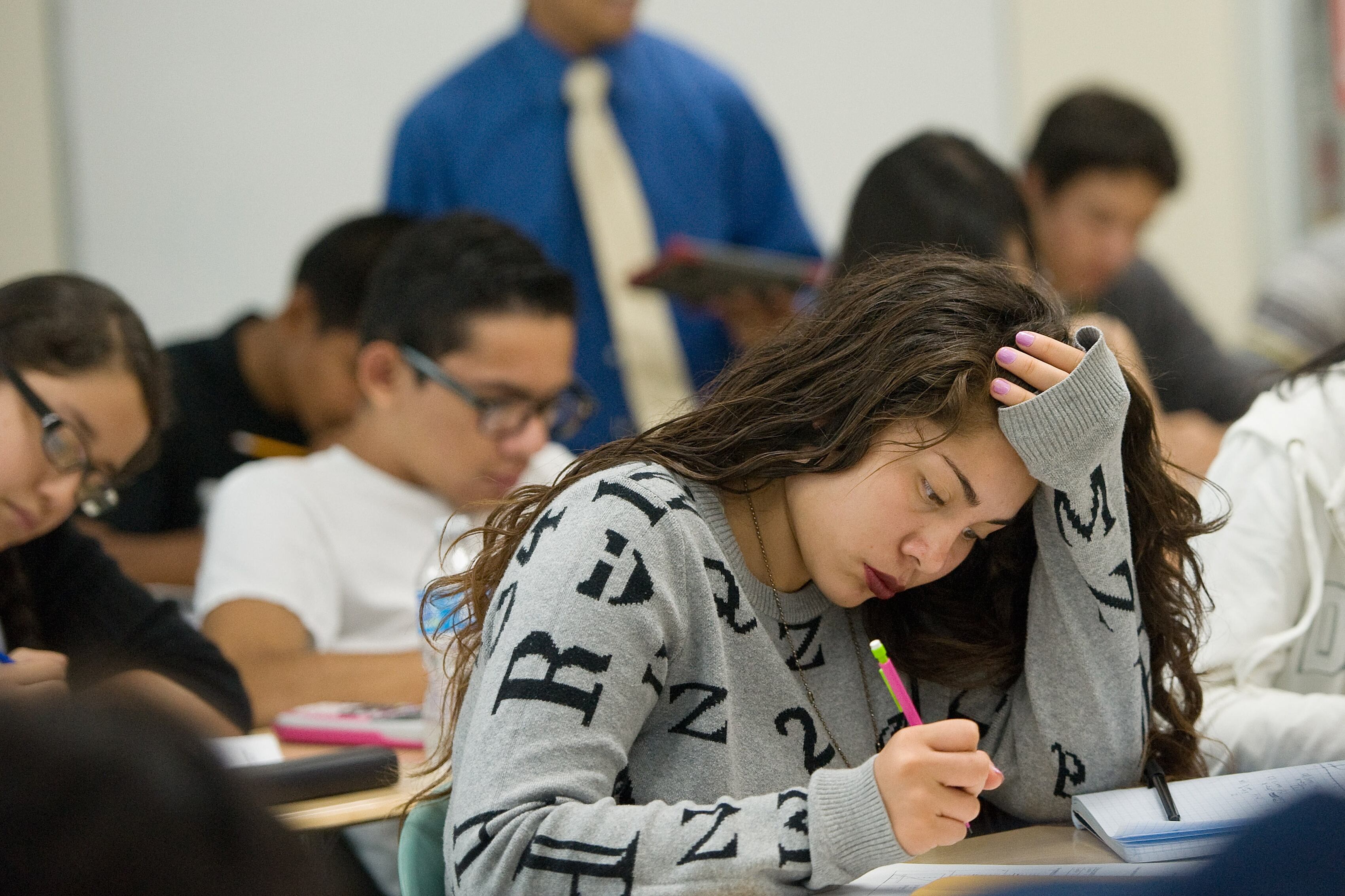

Some 2.4 million students are expected to take their AP exams from home by laptop, tablet, and smartphone this week and next, a change brought on by the coronavirus pandemic. The tests are shorter — 45 minutes instead of three hours, in most cases — and will focus on content students learned earlier in the year before classes were upended.

The change has raised questions about whether the at-home, online format will disadvantage students who don’t have fast internet connections or devices at home, especially students from low-income families or in rural communities — two groups the College Board has targeted in recent years as it pushed more schools to offer AP classes.

What is clear is that the new format means the worries typically shouldered by testing sites and adult proctors have been transferred onto teenage students, who have very different abilities to guarantee their access to technology or even quiet conditions.

Muñiz, for one, is crossing his fingers that his test doesn’t get interrupted by noise from outside his bedroom window.

“Sometimes there’s a lot of people that walk by and they have their radios really loud,” he said.

The College Board has said that nearly all AP students have access to a smartphone, and that the organization responded to 10,000 students who contacted their outreach team to help them find a device or internet connection, often through their school district.

In Detroit, though, officials say 100 students who didn’t have devices or internet access weren’t able to get in contact with the College Board. That prompted the school district to open school buildings so students could take the exams in person, overseen by school administrators.

On Monday, the first day of the at-home exams, several students and teachers told a top College Board official via Twitter that they or their students had issues submitting all or parts of their AP Physics C: Mechanics exam online.

In response, College Board senior vice president Trevor Packer said of the 50,000 students who’d taken the test, “approximately 2% encountered issues attempting to submit their response.”

“Given the wide variety of devices, browsers, and versions students are using, we anticipated that a small percentage of students would encounter technical difficulties, and we have a makeup window in June so students have another opportunity to test,” Packer wrote.

On Monday evening, the College Board said more than 376,000 students had taken one of the three exams given that day and that less than 1% had “encountered technical difficulties.”

The College Board pointed to statements from many colleges and universities that say they will still offer credit for the shortened AP exams, though some colleges and admissions counselors have expressed concerns about whether the at-home exams will be secure and reliable.

On Monday, Packer said the College Board had “cancelled the AP exam registrations of a ring of students who were developing plans to cheat, and we’re currently investigating others.” While students can consult their textbooks and notes for the test, they’re not supposed to talk with other students or adults during the testing time.

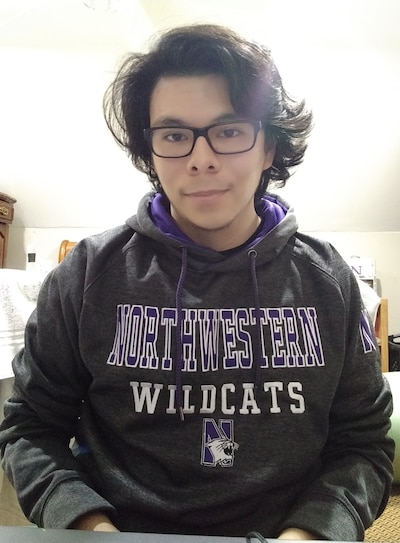

The new test format has been an adjustment even for students who are no stranger to the difficult exams. Muñiz’s classmate, 18-year-old Arturo Ballesteros, was one of only 100 students in the world to ace the AP Spanish Language and Culture exam last year.

To get ready for the calculus exam, he too practiced submitting his test online. That worked fine, but he worries that the camera quality on his phone “isn’t the best.” So he plotted out where the best light in his house would be at the time of the exam — by the window in his living room — and plans to set up a table there.

Muñiz and Ballesteros have been studying together by video chat and checking in with their teacher for regular Google Meets, though Ballesteros has noticed many of their classmates haven’t been attending consistently.

With all of the digital uncertainties, they both took heart from something that arrived by snail mail: A handwritten note from their teacher with words of encouragement.

“It helped boost my overall mood and confidence when it comes to this modified exam,” Ballesteros said. “Especially with all the things that could go wrong. But this note has reassured me, and it’s like: Everything is going to be fine.”

This story was updated to include additional information provided by the College Board on Monday evening.