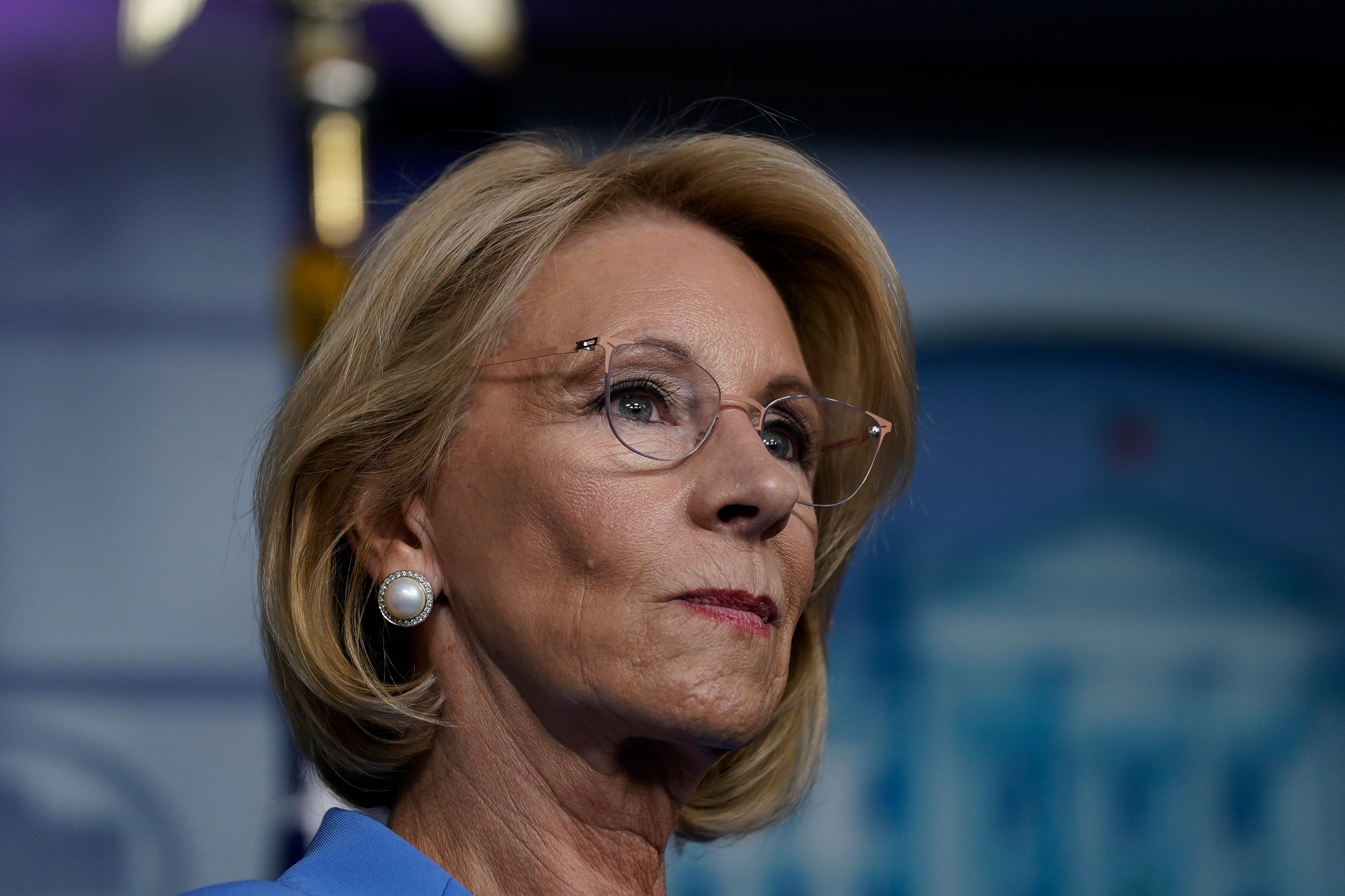

Education Secretary Betsy DeVos said Tuesday that the coronavirus pandemic has offered a chance to advance a longstanding goal of hers: to use public dollars to support access to private schools.

In a conversation with DeVos on SiriusXM radio, Cardinal Timothy Dolan, the Catholic archbishop of New York, suggested that the secretary was trying to “utilize this particular crisis to ensure that justice is finally done to our kids and the parents who choose to send them to faith-based schools,” including through a new program that encourages states to offer voucher-like grants for parents.

“Am I correct in understanding what your agenda is?” Dolan asks.

“Yes, absolutely,” DeVos responded. “For more than three decades that has been something that I’ve been passionate about. This whole pandemic has brought into clear focus that everyone has been impacted, and we shouldn’t be thinking about students that are in public schools versus private schools.”

The comments are DeVos’ clearest statement to date about how she hopes to pull the levers of federal power to support students already in — or who want to attend — private schools. She has already made that intention clear with her actions: releasing guidance that would effectively direct more federal relief funds to private schools, and using some relief dollars to encourage states to support alternatives to traditional public school districts.

In another respect, though, the comments are surprising. In an interview last week, DeVos attempted to contrast her competitive grant program with the Obama administration’s much-larger Race to the Top initiative.

“I don’t see any parallels, to be honest. Race to the Top was wholly designed by the Obama administration to advance their policy priorities,” she told Rick Hess of the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank. “Our discretionary grant competition is completely the opposite. … Yes, it is focused on reforms, but they are reforms that any intellectually honest person would have a hard time arguing aren’t needed.”

But DeVos’ comments Tuesday were a straightforward acknowledgement that she does see an opportunity to advance her policy goals.

Asked about those comments, Angela Morabito, a department spokesperson, said in a statement: “There is no question that this crisis has impacted all students, no matter what kind of school they’re enrolled in.” DeVos, she said, “is helping Catholic schools just as she is helping all schools; this does not mean she is favoring any one type of school over another.”

DeVos’ approach has already proven controversial among public school advocates, who fear these moves will shift money away from public school students, particularly those from low-income families.

But the coronavirus relief may serve as a lifeline to private schools. HuffPost reported that at least 100 Catholic schools across the country are likely to close next year. An economic downturn will likely mean fewer students will be able to afford private school tuition, which could mean an influx of new students to public schools, further straining budgets.

In a recent letter, private school organizations and advocacy groups urged Congress to allocate funding to support private schools in any future relief package. “We believe there must be dedicated funding and tax policy changes to prevent massive non-public school closures,” they wrote.

These advocates have an ally in DeVos, whose department has interpreted the federal coronavirus relief law in a way that helps private schools in particular.

In one instance, the CARES Act says that private schools are eligible for services as part of the relief package in the “same manner” as they are under Title I in the federal education law. Title I says the amount of money dedicated to those services should be determined by the share of low-income students who attend private schools. Guidance issued by DeVos’ department, though, says this calculation should be based on the share of all students in an area who attend private schools.

Because private schools as a whole serve smaller numbers of low-income students than public schools, this interpretation would lead to more dollars going to support private schools. At least two states — Indiana and Maine — have said they won’t comply with the federal guidance.

In another example, the CARES Act instructed the department to award over $300 million in grants to states with the “highest coronavirus burden.” Much of that money, DeVos determined, will be allocated through a competitive grant program that encourages states to offer “microgrants” for parents, create a statewide virtual school, or propose novel ideas for providing remote instruction.

A state’s coronavirus burden accounts for 40 of the 100 points on the rubric used to determine which states will win a grant. That means states with relatively low burden could, in theory, win funds.

A spokesperson for the department said this week that 17 states had indicated they intended to apply for the program, but declined to say which states.

The full interview excerpt is below.

Timothy Dolan: Let me see if I understand the steps you’re hoping for and that I’m enthusiastically behind you and the administration on. I think you’re speaking about short range and long range, if I understand correctly. Short range is to make sure that all the non-governmental schools, the nonpublic schools, do share — parents, teachers, children especially — in the emergency aid that is flowing through the country. Thanks to the president, thanks to the Congress and you and president Trump — but I give credit as well to the Democrats, I know I’ve worked closely with Senator Schumer — in getting that to happen. And that is happening, and that’s probably going to allow us to get through the current academic year.

But stage two, I understand, Secretary DeVos, is a particularly passionate dream of yours, namely let’s utilize this particular crisis to ensure that justice is finally done to our kids and the parents who choose to send them to faith-based schools through agencies like these educational scholarship microgrants — that would be more long range. Am I correct in understanding what your agenda is?

Betsy DeVos: Yes absolutely. For more than three decades that has been something that I’ve been passionate about. This whole pandemic has brought into clear focus that everyone has been impacted, and we shouldn’t be thinking about students that are in public schools versus private schools and making an artificial separation between children in K-12 grades and, for example, those in higher education. We don’t make that distinction there. We don’t make that distinction when it comes to hospitals. There are many wonderful Catholic hospitals across the country that are serving patients, and importantly serving them well right now. But we don’t make those artificial distinctions at any other level in any other place. So we need to be focused on ensuring that students whose families want to have them in religious schools, such as Catholic schools, continue to have that opportunity to do so, and that others can actually elect to make that choice if that’s the right thing for their children.