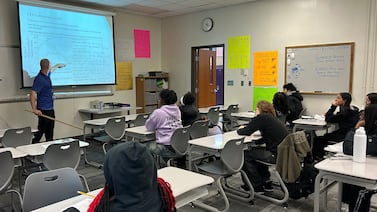

Just a few months back, high school students learning English as a second language in the Adams 14 school district outside Denver spent 53 minutes a day in a special class dedicated to building up their language skills.

When school buildings went dark and learning shifted online, that practice ended. High schoolers learning English in the heavily Hispanic, mostly low-income district started getting language assignments twice a week instead.

In elementary schools, children got 30 minutes of remote instruction in English and math each day. Teachers were supposed to incorporate language skills into that work, but students missed out on 55 minutes of daily English language development they received before the virus struck.

The rapid shift to remote learning forced by the COVID-19 crisis has left the nation’s roughly 5 million English language learners in a precarious position. Many have seen their language instruction shrink as districts balance competing priorities and struggle to connect with students attending school from their living rooms.

Schools and districts have largely had to figure out how to meet the needs of English learners on their own. It wasn’t until this week — when most schools had been teaching students remotely for two months, and some were ending the school year — that the U.S. Department of Education issued guidance clarifying that educators must continue to provide English language support “to the greatest extent possible” during the pandemic.

And while some districts crafted remote learning plans that took into consideration the unique needs of English learners and their families before the guidance was handed down, that hasn’t been the case everywhere.

The stakes are high because English learners risk learning loss on two fronts. Without language development help, students’ progress toward mastering the English language is slowed, and their ability to pick up subjects taught to them in English gets hurt, too.

“The extent to which children are not getting opportunities to hear and speak the English language I think is a huge concern,” said Amaya Garcia, the deputy director for English learner programs at New America, a left-leaning think tank based in Washington. “Nationally, most of what I’ve seen is that it’s been a challenge. We have information about all the barriers that exist. School districts can use that information to create some kind of solution moving forward.”

The challenges in Adams 14

About half of Adams 14’s students are learning English as a second language, giving the district one of the highest proportions of English learners in Colorado. The vast majority of residents in the heavily industrial inner-ring Denver suburb are Hispanic, and most are low-income.

Like other districts serving high-needs students, Adams 14 had to scramble to make sure its 6,500 students could get online at all when school buildings closed. For the first few weeks of remote learning, educators and staff spent much of their time making sure students had computers and internet access.

“It’s been about, ‘Can you get on? Are you getting on?’” said Tonia Lopez, Adams 14’s director of culturally and linguistically diverse education and instruction.

Latino students, who make up about eight in 10 English learners nationally, are disproportionately likely to rely on their cell phones to get online at home — which can work in a pinch, but can be hard to use for all school assignments.

While Adams 14 was working out those technical issues, officials were also figuring out how to continue teaching and learning. They settled on a plan that had several phases including “choice boards” at the beginning that just gave students ideas for activities to work on, then transitioned into more live video classes and online assignments through Google. The district prioritized English language learners in developing that remote learning plan, a district spokesman said.

The district was under particular pressure to get it right. An investigation by the federal education department’s Office for Civil Rights concluded in 2014 that the district had discriminated against Spanish-speaking staff, students, and their families. Adams 14 agreed to a federal order to improve how it educates English learners.

Last year, Adams 14 also became the first district in Colorado forced by the state to hand over daily management to a private company after years of low academic achievement. That company, MGT Consulting, had been working with district staff and the Office for Civil Rights on a comprehensive plan for educating English learners before the pandemic.

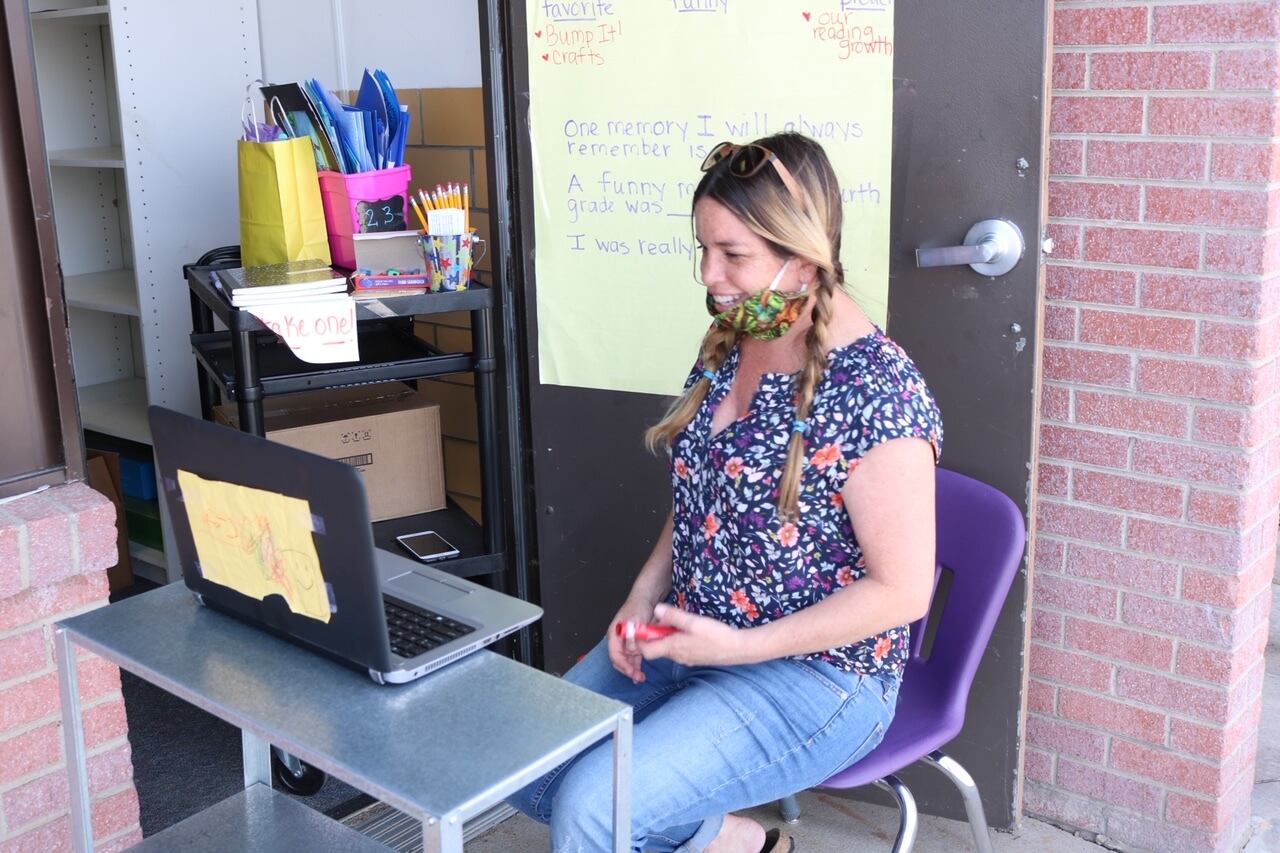

When COVID-19 moved learning online, the district made new attempts to reach its English learners. Teachers and other staffers have translated materials for parents, and teachers of English learners have been available for students to ask for help by phone, video, and text.

Those teachers have also been consulting and coaching teachers of other content classes, to make sure that assignments are understandable to English learners. All district teachers had been training all year to better tailor their lessons and assignments for the many English learners they serve.

“We have been building off of a framework that makes sure we are all comprehensive and thoughtful of language in all of our lessons that we plan,” said Traci Whitfield, a fourth-grade teacher in Adams 14. “To me, it just makes sense to build lessons this way.”

Whitfield said that in her class of 21 students, more than two-thirds are English learners. About 85 percent of students on average engage in remote learning in some way on a daily basis, she said.

But the transition has still been tough. Maria Rodriguez, a stay-at-home mother of three Adams 14 students, recently learned that Jahaira, her 11th grader, was skipping some live classes.

Jahaira has struggled to advance in her English proficiency and was enrolled in English language development classes when school buildings closed, Rodriguez said. She worries that her daughter is having trouble with remote learning, in part, because she’s not getting the same level of English language development now.

Jahaira told Rodriguez she can’t always understand her teachers, partly because of the language.

“It’s harder now,” Rodriguez said. “She always needed teachers to explain more to her, and now that it’s through distance learning, it’s more complicated. She is timid and she may be too shy to ask questions.”

“I’m not sure how else to help them,” Rodriguez said of her children.

Officials in Adams 14, like in other districts, acknowledge that schools have decreased the time they spend on language development, just as they’ve had to decrease time spent on all kinds of instruction to make this new setup work for students and teachers.

“The time is different, because we’re not expecting our kids to be on for eight hours a day,” Lopez said. “We’re all trying to do our best.”

A complicated national picture

While all English learners are entitled to language help, they do not have legally binding education plans like students with disabilities. Their instruction varies widely, depending on state law and district policies, and advocates say it was hard to enforce the civil rights of English learners even before the coronavirus.

“School districts have a lot of leeway to determine how they’re delivering the services for students,” said Garcia, of New America. “We have all these legal obligations, but how are they actually being carried out right now?”

The federal guidance issued this week emphasizes that schools must continue to provide language support for English learners remotely, but acknowledges it may not be possible to do it at the same level as before the pandemic. It notes there is no standard amount of time that must be devoted to English language services.

The department also cautioned that districts should continue to monitor English learners who demonstrated proficiency before schools closed in March, saying it’s possible they will need extra help when buildings reopen — an acknowledgment of the learning loss many students are experiencing right now.

Advocates say if English learners receive reduced services it may be hard to make the case there’s been a civil rights violation, given the wide range of instruction that’s permissible in normal times, as well as how much districts have had to contend with during the pandemic.

On top of that, the Trump administration doesn’t have a strong history of enforcement. Under Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, the education department’s Office for Civil Rights has opened fewer systemic investigations and has been less likely to uphold complaints of discrimination against English learners than under the Obama administration.

Looking forward

Figuring out public education in the age of COVID-19 is now entering another chapter: School districts are beginning to plan for the fall. Many of them, including Adams 14, will have a long to-do list to make sure English language learners get the services they require, including testing for English proficiency and deciding which courses are appropriate.

As classes ended this week in Adams 14, students, parents, and educators headed into the summer break unsure of what school will look like in the fall.

A number of school districts in the Denver metro area, including Adams 14, are working collaboratively to find common solutions. The hope is to create a unified plan, in part because teachers have children of their own enrolled in districts other than where they teach.

Among the options on the table: hybrid approaches combining remote learning and limited in-person learning. Most districts haven’t released details of what their plans might look like, and final plans likely won’t be available until later this summer.

If virtual learning does continue in the fall, some teachers say they’d like to increase instructional time for students, including time for more deliberate English language development.

And parents like Aracely Gomez of Denver are hoping their children will benefit from a more normal learning schedule and more time learning English.

Her 6-year-old daughter is in a program that begins students with mostly Spanish instruction and gradually transitions to English. That Spanish instruction is continuing from home, Gomez said. But she’s worried about how the transition to English is going to work if her daughter hasn’t been getting academic English practice at home.

“She does practice with her older sister,” Gomez said. “But I know it’s not the same as the English she would get at school.”