In response to the anguish and outrage that have followed the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis last week, at least eight charter school networks have taken the extraordinary step of canceling a day of class.

School leaders said they have encouraged class discussions about recent police violence against black people and the nationwide protests that erupted in response — but that students and staffers also need time to themselves to heal and reflect.

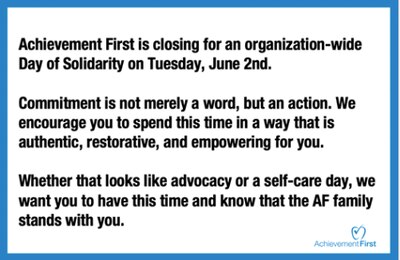

“You can’t expect people to witness such dehumanizing murders and the continued painful pattern and truth they represent, and then show up to work or school and go about business as usual,” said Dacia Toll, the president of Achievement First charter schools. “It is not possible, and it is not right.”

KIPP Minnesota appears to have been the first to cancel classes on Friday for its three schools in Minneapolis, where demonstrations have been among the most sustained and clashes with police the most intense.

They were followed this week by groups of KIPP schools in Newark, New York City, and Washington D.C.; Achievement First, which has schools in New York, Connecticut, and Rhode Island; the Alliance College-Ready schools in the Los Angeles area; Uncommon Schools in Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York; Ascend schools in New York City; Rocky Mountain Prep in Colorado; DC Prep in Washington, D.C.; and Great Oaks Legacy Charter School in Newark.

The networks said their school communities could use the day off for advocacy or reflection. Several said they specifically wanted to give black students and employees time to process recent events and care for themselves.

“It became abundantly clear that we — even myself, as a black woman — were grieving and struggling with the events that have been happening,” said Juliana Worrell, chief schools officer at Uncommon, which designated Monday a “mental health day” for its staffers and more than 20,000 students. “It was a difficult decision to close today, but it was the right decision.”

The cancellations appeared to be limited to charter schools, which are publicly funded, independently operated, and often non-unionized, giving them more flexibility than traditional district schools to quickly change their staff’s work schedules. Many of these charter networks almost exclusively educate black and Hispanic students and operate in cities that have erupted in protests in recent days.

Some networks, such as KIPP Minnesota, continued certain school operations, including meal pick-up and a mental health hotline. Others, like Alliance, directed students to the grab-and-go meals offered by the local district, Los Angeles Unified. The logistics of canceling classes were made easier because schools are functioning remotely due to the coronavirus pandemic, but some school leaders said they would have closed regardless.

Many of the charter networks have faced criticism in the past for a “no excuses” approach that contributed to high rates of discipline for students of color, especially black students. Some have since led efforts to reduce suspensions, hire more teachers of color, and offer more training on culturally sensitive teaching practices, though debates over the schools’ strategies continue. And some have taken strong public stances against racism and in support of black and brown lives in recent years. The decision to cancel classes falls in line with those recent moves.

Some white network leaders added that the decision was an act of solidarity with their black students and colleagues.

“To my Black and Brown colleagues, scholars, and families, I can’t know what it is like to be in your shoes right now,” said a letter from James Cryan, the CEO of Rocky Mountain Prep, which operates four charter schools in the Denver area. “I can’t imagine the pain, fear, suffering, and exhaustion.”

“I can interrogate my own privilege and continue to strive for communities built on belonging, safety, and love,” he added. “I charge my white colleagues to do this as well.”

Educators across the country planned virtual lessons and class discussions following the events in Minneapolis, where Floyd, a black man, died after a white police officer kneeled on his neck for nearly nine minutes. The death, which has been ruled a homicide and led to a murder charge for the officer, sparked demonstrations in dozens of cities where protestors demanded justice for Floyd and an end to police brutality and systemic racism.

But some school leaders felt that black students and employees in particular also needed time away from their school responsibilities — especially given the stress that has come with months of sheltering in place and working from home during the pandemic.

“Just dealing with that has already been challenging enough,” said Worrell of Uncommon Schools. For black educators, herself included, the widely circulated video of Floyd’s death last week compounded the stress and exhaustion that many already felt.

“As a black mother, seeing the events unfold, hearing George Floyd cry out, ‘Mama, mama’ before he died, there’s just an unspeakable burden and pain that I think all mothers feel, but black mothers feel especially,” she said.

Modiegi Notoane-Eugene, the principal of Newark’s Thrive Academy, a KIPP elementary school, had a similar reaction to Floyd’s killing.

“As an educator, before I can even put that hat on, I had to think of myself first as a black woman,” she said, and “the rage that I felt towards the things I have seen over and over again.”

On Monday, Notoane-Eugene organized a virtual staff meeting. She invited a Rutgers University professor to offer suggestions for how her staffers could process the recent events personally and address them with students.

Notoane-Eugene said she was motivated in part by an email she received that morning from her children’s teacher in a school outside Newark. The teacher said she hoped students had a “beautiful weekend” without mentioning Floyd or the protests that have gripped the nation. By contrast, Notoane-Eugene expects her staff to address the recent events in their check-in calls with families and their lessons this week. And she plans to adjust her end-of-the-year message to her school’s students, 86% of whom are black.

“They have to know that their lives matter and they have value regardless as to whatever the outside world says,” she said.

Traditional school districts are limited in their ability to call off school on short notice, largely because labor agreements dictate school holidays and staff training. However, many of the country’s schools superintendents have made public statements denouncing Floyd’s killing, linking his death to similar examples in their own cities.

Some large districts, like Chicago and Los Angeles, have issued guides to help teachers discuss racism and police violence in their virtual classrooms. And the Minneapolis school board is scheduled to vote Tuesday on a resolution to cut the district’s ties to the city police department.

Even before the recent unrest, some districts have pursued policy changes that officials say are intended to promote racial justice. In Newark, for example, the district has purchased textbooks that better reflect the experiences of students of color, trained security guards on conflict de-escalation and ways to avoid suspensions, and sought to hire more black and Hispanic teachers, said school board member A’Dorian Murray-Thomas.

Murray-Thomas, who spoke Saturday at a rally for Floyd in Newark, said teachers must now take class time to address the protests and help students respond to the racism many experience in their own lives.

“Our young people are hurting and they’re angry,” she said. “Not only do they want their voices heard, but they’re passionate about doing something about it.”

Since closing on Friday, KIPP Minnesota has looked for additional ways to support its 488 students, nearly all of whom are black, and its 100 staff members. This week, classwork is optional for students. But classes themselves will continue in an effort to offer consistency for students who want that, with KIPP staff filling in for any teachers who need it, said Katie Hayes Antelo, KIPP Minnesota’s head of schools.

The schools also gathered donations — enough to fill a gymnasium and several classrooms — of food and supplies like diapers, toilet paper, and hand sanitizer for students and their families who lost access to their local grocery store or pharmacy when buildings were burned or looted. Families will be able to pick them up Wednesday, Antelo said, and students will also be able to paint murals, while socially distanced, as “a visible presence of our fight against injustice.”

Going forward, Antelo said, the organization will be evaluating whether its summer school program should incorporate “fighting for justice,” too.

“I hope that schools across the country, starting with us, recognize that we need to step up and act with our families, both now and in the future,” Antelo said. “We need to listen to what they need, both in moments of crisis and when moments of crisis pass.”

Claire Bryan contributed reporting.