This spring, America’s schools underwent an unprecedented experiment: tens of millions of students stopped going into school, and instead began receiving instruction remotely.

So — now that the school year is over almost everywhere — how much remote learning actually happened? And who was served best, and worst, by this new approach?

Definitive answers are hard to come by, and national data on student learning is virtually nonexistent. But more than a dozen national surveys of teachers, parents, students, and school administrators conducted over the past few months offer the clearest initial tally of successes and failures.

The surveys offer more evidence that educators were right to worry that remote learning would exacerbate inequities. Over and over, Black and Hispanic students and students from low-income families faced more roadblocks to learning, driven in part by gaps in access to technology and the internet. And engagement with schoolwork was relatively low across the board, reflecting the challenges of keeping students engaged in a chaotic time and of teaching from a distance.

But the surveys also show that most of America’s teachers did rapidly overhaul how they worked, and most parents gave their children’s schools high marks — evidence that the reality of remote instruction was somewhat more complicated than outright failure.

“The challenge and the scale of what we were asking a system that employs almost 4 million teachers to do on short notice with limited infrastructure was herculean,” said Matt Kraft, a Brown University professor who developed a recently released teacher survey. Still, he said, “It’s hard to explain — without wondering if some districts could have done a lot better — why there were places that were much more successful.”

Here are the most notable takeaways, and what they can tell us about planning for next school year.

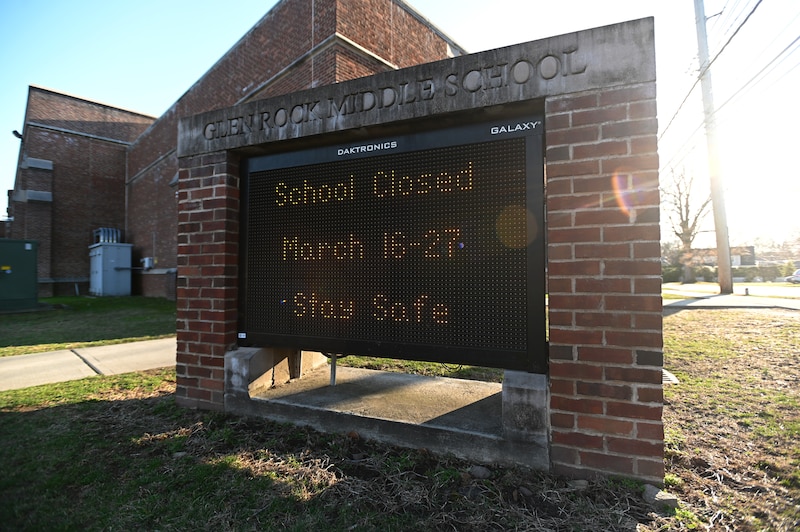

The vast majority of schools pivoted quickly to remote instruction in some form.

When school buildings initially closed, some school leaders said they didn’t have the capacity to move to remote instruction. But that rapidly changed.

One survey found that soon after schools closed in late March, 65% of parents reported some sort of online learning; by early April, that number had jumped to 83%. Separate surveys in May showed that 95% to 99% of teachers were facilitating remote instruction, and nearly 90% of families said their children had received educational resources from school.

Student engagement with remote schooling was relatively low.

Teachers in two separate surveys estimated that only about 60% of their students were regularly participating or engaging in distance learning. (Individual district reports of daily “attendance” varied widely, as districts defined the term so differently.)

Two-thirds to three-quarters of teachers said their students were less engaged during remote instruction than before the pandemic, and that engagement declined even further over the course of the semester.

A survey of teenagers in late March found that most were in contact with their teachers less than daily, with a quarter saying they were in contact less than once a week.

“It’s very obnoxious to do,” Diego Angeles, a 10th grader in Aurora, Colorado, said in April of his online work. “It’s just boring and bland. I don’t think I’m learning.”

Teachers and parents agree: they needed help and lacked strategies to keep kids engaged.

When teachers were asked what they needed help with from their schools and districts, the number one response was “strategies to keep students engaged and motivated to learn remotely,” with nearly half describing this as a major need.

Parents agreed. Their most common need, according to another survey, was “help keeping my children engaged in good activities.”

That was the experience of Kymberly Calhoun, a parent of a Detroit high school student.

“I don’t know how to reach him as far as education,” she said in April. “Sitting around is really driving him crazy. He’s very active, and keeping him in the house and not being able to go further than the yard is like being locked up in jail for him.”

Remote learning had massive equity issues, with engagement varying across racial and economic lines.

Teachers of low-income students and students of color were much more likely to report that their students were not regularly engaged in remote learning.

51% of teachers in high-poverty schools reported that most of their students were participating daily in distance learning. For affluent schools, the number was 84%.

Many factors could explain these disparities: Technology access issues; responsibilities at home, including caring for siblings; stress from the pandemic, which disproportionately hit people of color; and a lack of interest in work that in many cases went ungraded or didn’t cover new material.

In one survey, 51% of teachers in high-poverty schools reported that most of their students were participating daily in distance learning. For affluent schools, the number was 84%.

Another survey of several districts found that teachers with few Black students reported engagement rates of 60 to 70%. In schools serving predominantly Black students, the number fell below 50%.

A May parent survey found that about 85% of the most affluent families said their child had interacted with their teachers since schools closed, compared to 62% of the lowest-income families.

Even months after school buildings closed, many students lacked the internet access and devices they needed.

Many school districts raced to deliver computers to students and make the internet available in some form. But several surveys showed that access issues remained among the biggest challenges faced by schools and students, particularly in high-poverty districts.

“It’s beyond frustrating,” Keyshawn Woodbury, a New York City parent of a 6-year-old son who didn’t receive an iPad from the district for weeks, said in April.

Even in early May — a month and a half after most buildings shut down — the lack of technology was a serious impediment, teachers reported. One survey found that about a third of teachers in high-poverty schools described access issues as a major limitation, with the vast majority describing it as at least a minor hurdle. Principals reported home internet access as the top issue limiting distance instruction.

Among the lowest-income parents, only about half said in early June that a device was always readily available for their child to use for school. (Many who did have a device said it was provided by their child’s school.) The vast majority of students from the most affluent families, on the other hand, always had a device. Disparities were nearly as wide for home internet access.

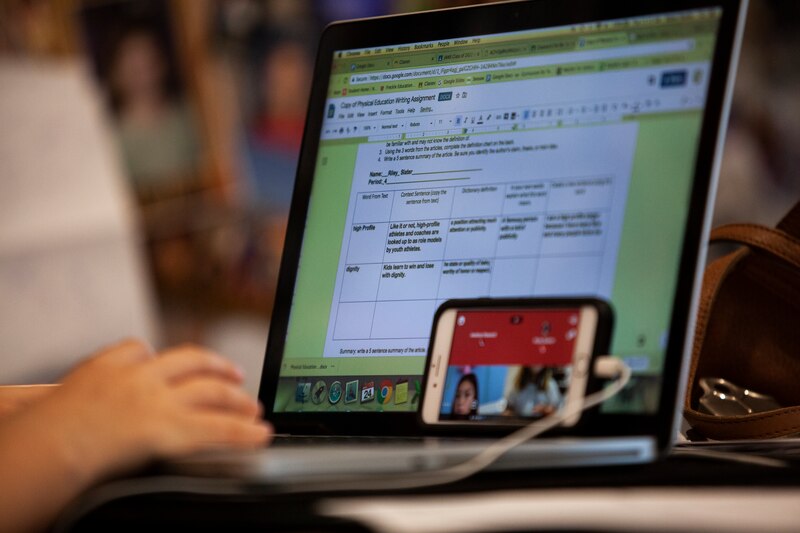

What distance learning actually looked like varied a lot from school to school.

Prior to the pandemic, virtually every high school in America gave out grades. Virtually every school had a teacher personally connecting with and teaching students each day.

Once the pandemic began, schools’ practices varied much more widely. For instance, only a third of teachers reported giving letter grades, while another third said they issued pass or fail grades. Most teachers said they didn’t get through most of their planned curriculum, but a substantial minority did.

Meanwhile, about 70% of teachers reported holding live instruction with students at least once a week, though again a good number said they did so rarely or ever. Teachers also varied in how frequently they provided students with feedback on their work: while a third reported doing so daily, another third did so only weekly.

Low-income students of color were more likely to be tasked with reviewing material, rather than learning new concepts.

Even when students were connected and learning, low-income students were more likely to be reviewing material, not learning new concepts, a number of surveys showed.

For instance, in one survey that zoomed in on schools with mostly Black, Hispanic, and low-income students, only 22% of teachers reported spending all or most of their time on new content, compared to 43% in other schools.

According to another analysis, half of high-poverty school districts appeared to be offering only “perfunctory” instruction, compared to a third of wealthier districts.

Educators in one Denver-area district say their focus on reviewing material was deliberate.

“We wanted to focus on welfare checks and on helping students retain what they had already learned,” said Kathey Ruybal, the president of the local teachers union.

But others worry that this likely contributed to equity issues. “If you’re doing the same old thing all the time, it’s obviously going to lead to engagement problems,” said Darleen Opfer, a researcher with RAND, which surveyed principals and teachers.

Some students with disabilities did not receive the support they were entitled to.

About 20% of parents of children with disabilities said their child was not receiving required special education services in May.

Among 501 school district superintendents from across the country who responded to a survey, 83% said that providing special education services was difficult to provide equitably during remote learning.

For parents, those missing services often added to the challenges of online schoolwork.

“He would not be able to complete the work on his own and he would never log back on,” New York City parent Amy Schindler said in June of her son Joseph, who has Asperger’s and ADHD. “It required executive functioning skills that Joe doesn’t quite have.”

Parents gave their kids’ schools fairly high marks — but also believed their kids lost out on learning.

Perhaps recognizing the challenges inherent to a sudden switch to remote learning, most parents felt positively about their schools’ remote instruction efforts, multiple surveys showed.

A May survey found 72% of parents said their child’s school was doing a good or excellent job at providing support for distant learning; only 2% said schools were during a poor job.

A May survey found 72% of parents said their child’s school was doing a good or excellent job at providing support for distant learning; only 2% said schools were during a poor job. Low-income families similarly gave their children’s schools high marks, on average.

A majority of parents even reported feeling more positively about the idea of homeschooling as a result of the remote instruction shift, another survey showed.

Still, many parents were concerned that their kids were falling behind academically or missing out on learning, polling shows. In one survey, low-income parents were particularly worried: three quarters said that they were somewhat or very concerned about their child falling behind in school.

“The comment from every single teacher was: things were going pretty well until we switched to distance learning,” said Schindler, the New York City parent. “I just feel like his education is seriously compromised if it is not in person.”

Chalkbeat relied on national or multi-state polls that used rigorous survey methods to gauge teacher, parent, principal, and student opinions, as well as national reviews of school and district policies. For teachers, we used polls by E4E, Education Week, RAND, and Upbeat. For parents, we used polls by EdChoice, Gallup, National Parents Union, Pew, USA Today, USC, and the U.S. Census. For students, we used polls by America’s Promise and Common Sense. For principals, we used a poll by RAND. For superintendents, we used a poll by AASA. For school district policies, we used analyses by AEI and CRPE.