When Congress passed a coronavirus relief package at the end of March, it offered schools a $13.2 billion lifeline to cope with the many unexpected costs of the coronavirus pandemic.

But just over three months later, many districts have yet to benefit from the main pot of federal money meant to help schools.

That’s true for a variety of reasons. In many states, school leaders have had to submit multiple rounds of paperwork to get their money, which takes time. In several states, CARES Act funds are being used to make up for state cuts to education, so it doesn’t feel like much of a boost. Some school districts aren’t eligible for the funds.

And many school leaders are facing a mountain of uncertainties as they plan for the start of the new school year — from how widespread the virus will be in their communities, to what instruction will look like throughout the year — which makes it hard to know exactly what to spend the money on, and whether they should save some for the future.

“That’s what will keep you up at night. You can have a great plan and then, oh here’s something that no one ever thought of … and then we have to basically shift,” said Susan Willis, the chief financial officer for Wichita Public Schools in Kansas, where coronavirus cases have spiked in recent weeks. “All of those moving pieces make planning very difficult.”

On top of that, it’s widely acknowledged that the CARES Act isn’t nearly enough to cover the cost of what schools will need to operate in the coming school year and beyond, especially because many districts are likely to see their budgets slashed as local and state tax revenue falls.

Without another federal aid package, many school leaders and education advocates say, schools will have to use up their savings or make deep cuts.

Sarah Abernathy, the deputy executive director of the Committee for Education Funding, which advocates for more federal investment in education on behalf of many education groups, describes the CARES Act as a “down payment.” She says it’s likely schools will see more federal aid, but it’s unclear when.

“We’re running up against the clock,” Abernathy said. “Money won’t fix everything, but it will make a big difference to school districts being able to afford some of the things they’re going to need. But you can’t spend federal money until it comes to you.”

Congress set up the main $13.2 billion emergency education fund in the CARES Act to quickly help school districts and charter schools pay for new costs associated with the coronavirus pandemic. Districts don’t get all of that money; state education agencies can keep 10%, and districts have to set aside some money for private schools in their area.

The law allows districts to spend their money on a broad range of things, from laptops and internet hotspots to cleaning supplies, face masks, teacher training, and even staff salaries. Districts can use the money to cover the costs from last spring or to make purchases for the new school year. They have until next fall to spend it.

Schools are only just starting to tap this money. By the end of May, about 1% of that $13.2 billion had been spent, according to a recent federal report that looked at CARES Act spending.

That hasn’t changed much yet. Figures provided by state education agencies indicate that in Delaware, Illinois, and Virginia, districts and charter schools have been reimbursed for less than 1% of the money available to them. In some places it’s higher: Montana schools have spent and been reimbursed for about 4%, while South Carolina schools have spent about 7%. Kansas schools have spent and been reimbursed for about 9%.

Part of that is because it’s taken time for the money to reach districts. States had to apply to the federal government for their share, and school districts generally had to apply to their states, which is typical for a large federal grant program. In many states, school districts also have to seek approval as they spend the money.

Some districts haven’t applied for their share of the money yet. Miami-Dade County schools in Florida, for example, is still putting together its application, which is due next week, so it can access the $119 million it’s entitled to.

And in many places, school districts are still figuring out the best way to spend their money, sometimes changing up their plans as they learn more about the virus.

Wichita Public Schools, which serves about 49,000 students — just over three-quarters of whom come from low-income families — received around $17.9 million. The district has decided it will spend about $11 million of that on tablets and other technology for students and teachers, and about $4 million on cleaning supplies and personal protective equipment like masks — though Willis knows that figure could grow as it becomes clearer what instruction will look like in the fall.

More recently, Wichita officials have started to look at more expensive air filters, as more information has come out about how good ventilation may help prevent the virus from lingering in the air.

“It’s just this constant shifting based on more and more information coming out,” Willis said. And while she had hoped to save some of the money for next summer, realistically, she thinks it will be gone by September.

But in several states, the CARES Act dollars will mostly go toward making up for state budget cuts to education. That’s the case in Georgia, New York, and Texas.

Just south of Atlanta, Clayton County Public Schools, which serves about 54,000 students, nearly all of whom come from low-income families, is getting $17.5 million from the CARES Act. That will go toward Chromebooks, Wi-Fi for students, and staffing costs, says Superintendent Morcease J. Beasley.

But Georgia also cut Beasley’s budget by about $45 million, essentially wiping away those federal dollars and more. To make up the difference, Beasley said his district had to freeze staff salaries, dip into its savings, and cut school operations by about 15%. He’s making it work for now, but if the cuts keep coming, Beasley is already considering staff furlough days for the following school year.

“If this thing drags out beyond one year ... we don’t have an endless pot of savings,” he said.

Other school leaders are also worried about the future.

Greenville County Schools, which serves about 77,000 students in South Carolina, just over half of whom are from low-income families, is getting about $19.3 million from the CARES Act.

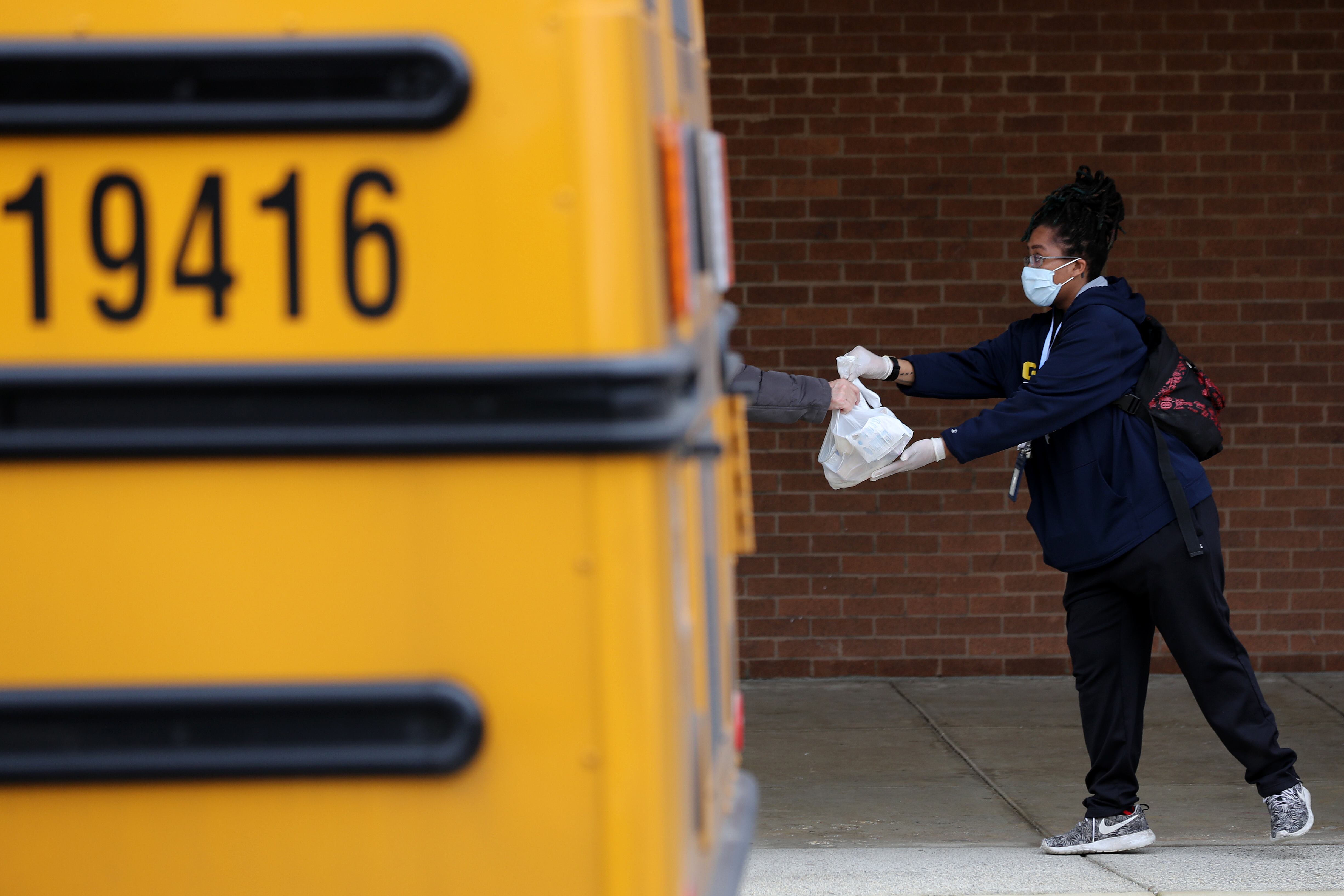

Superintendent W. Burke Royster said his district has asked to be reimbursed for about $8 million in costs from the spring, like driving buses with Wi-Fi hotspots to parts of the county that have low internet coverage so students could do their work, and continuing to pay all staff while buildings were closed.

The district intends to use another $1.5 million to cover extra cleaning and disinfecting costs, and will spend more to pay teachers this summer to design courses for the district’s new K-12 virtual school. But much of the rest Royster plans to hold onto for what he expects will be a very difficult 2021-22 school year.

“We’ll need that money to continue our operations,” he said. “I feel almost as certain as I can be.”

And while many agree that more federal aid is needed, exactly how much is up for debate. The Republican chair of the Senate’s education committee, Lamar Alexander of Tennessee, has estimated schools will need another $50 billion to $75 billion to reopen. A bill passed by the Democratic-led House includes about $58 billion for K-12 schools, plus more for states and local governments that could be used to avoid future education cuts.

Abernathy, of the Committee for Education Funding, points out that to cope with the last recession, K-12 schools and higher education received a lot more: $100 billion under the 2009 stimulus package. By comparison, the CARES Act gave just under $31 billion to schools and higher education.

Willis, in Wichita, says more funding would mean her district could consider extra health and safety measures it can’t afford right now, like putting up more plexiglass dividers — “they’re between, minimum $30 to $40 a student, so right now that would be cost-prohibitive” — and spacing out students more on buses. It could also help pay for another critical need: Making sure more students have home internet access.

“All of those things are kind of in the background waiting to see if there are additional dollars coming in,” Willis said.

And many school leaders are worried about the continued cost of providing personal protective equipment to staff and students, and what it will mean for their local economies if they have to lay off staff to fill future budget holes.

Beasley, in Clayton County, is buying face masks for students for now, but he worries it’s “unsustainable to expect the school system to provide all 55,000 students a mask every day of the school year.” His top priority, he said, is trying to keep all his staff employed so as not to add to his community’s unemployment rate.

“That’s why we need the federal government and Congress to step up to the plate,” Beasley said. “If they want kids to get back to school face-to-face, and we all do, then let’s put our money where our mouth is and let’s make it happen.”