As virus counts rise and teacher anxiety spikes, one big question is whether teachers unions will emerge as a powerful force in the school reopening debate — and whether a new wave of teacher activism could be on the horizon.

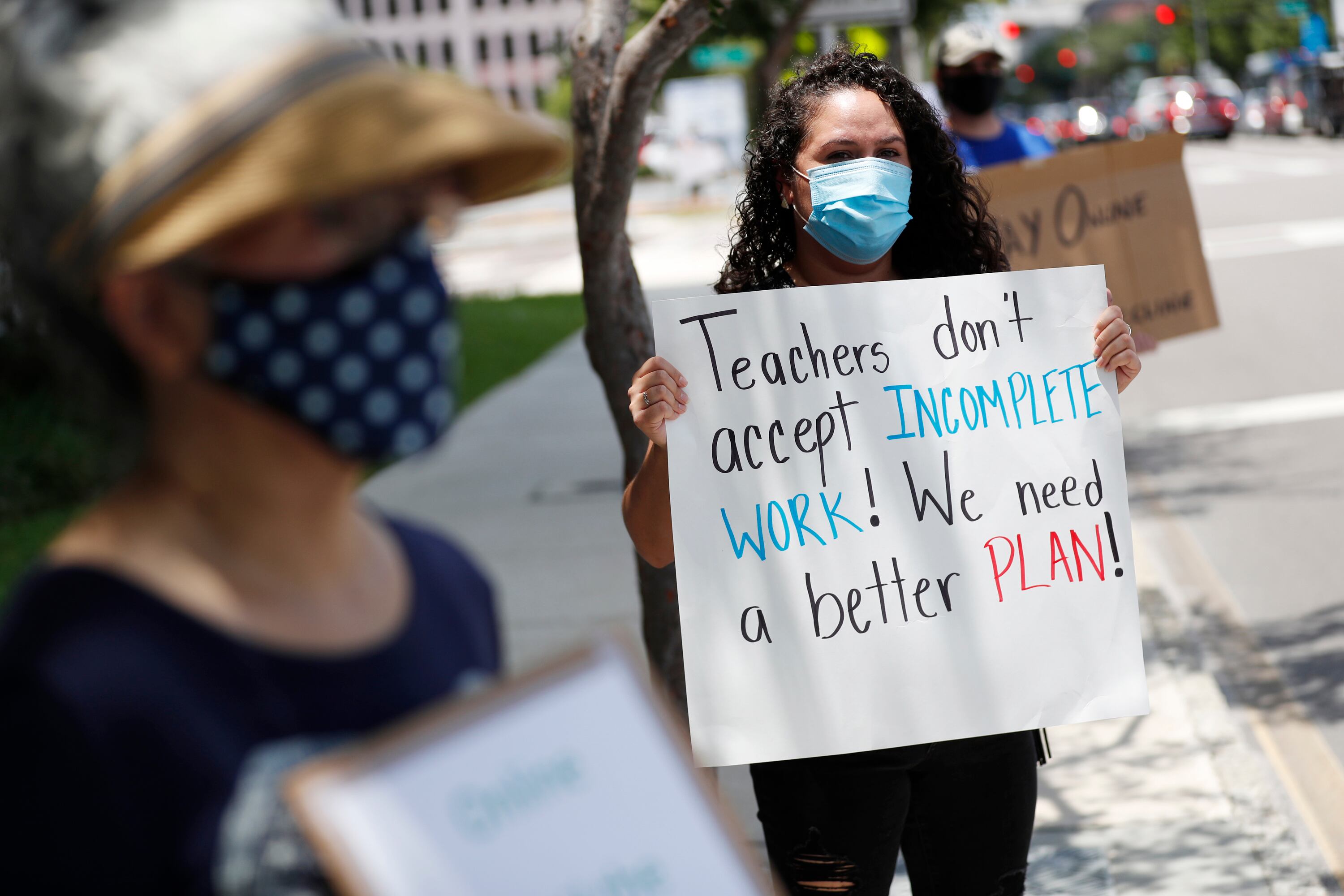

So far, the evidence is mixed. There have been a handful of protests over educator safety in recent weeks, from Loudoun County, Virginia to Austin, Texas. In Chicago, the union is getting louder and planning a “car caravan” protest over teacher safety this week. It was announced shortly after the union called for a return to remote schooling, but the school district said it planned to put most students in schools two days a week.

But many other teachers unions are keeping a lower profile as they hash out the details of school reopening plans, or as rising caseloads make reopening a public health impossibility.

That’s what happened last week as teachers unions in several large school districts, including Los Angeles, Houston, and Broward County, Florida, called for a return to remote instruction a few days before school officials made the call to do so — removing teacher health and safety concerns as a potential flashpoint for the time being.

But as school reopening plans get nailed down, and if teachers are asked to go back into school buildings when they don’t feel safe, more conflict could be on the way. Kisha Borden, the head of the San Diego teachers union, sees the potential for this moment to carry on the message of the Red for Ed movement.

“You would see teachers standing up, putting their foot down and saying, ‘No, I’m not going to put my life at risk,’” said Borden, whose union raised concerns about the San Diego school district’s initial reopening plans before officials announced a virtual start.

Teacher concern is coming from several places. Most important are questions of health and safety: While children appear to be at lower risk of getting seriously ill from COVID-19, there is new evidence that children of all ages can spread the virus, especially older children, which could mean school staff in close quarters are at risk of infection and passing the virus to others.

School reopening plans, and the particular ways schools are pledging to keep students and staff safe, are still up in the air in much of the country. The school reopening debate has also become increasingly politicized, as President Trump and Education Secretary Betsy DeVos — a particularly unpopular figure among educators — continue to put pressure on schools to fully reopen for in-person instruction.

All of that butts up against a real concern many teachers and parents have that remote schooling is often inequitable and a poor substitute for in-person instruction, especially for younger children and students with disabilities.

For now, teachers unions are walking a fine line.

Earlier this spring, both of the national teachers unions raised the possibility of strikes over teacher safety. Randi Weingarten, the head of the American Federation of Teachers, notably told Politico that if schools reopened without proper safety measures, “you scream bloody murder.”

Both the AFT and the National Education Association have struck a more moderate tone lately, as they’ve focused on lobbying Congress to give schools more money to help them cope with new costs and weather upcoming budget cuts.

On Monday, when asked what role teacher activism or labor action should play in the school reopening debate, Weingarten said the focus should be on addressing the surge of cases and getting schools the resources they need.

“If those things don’t come together, you can’t rule anything out when it comes to the safety and well-being of our kids and of the educators that teach them,” she said during a call announcing a lawsuit against Florida’s governor and education commissioner. (Florida has ordered school districts to offer five days of in-person instruction to parents who want it.)

Bradley Marianno, an assistant professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, has been tracking how teachers unions and school districts are adjusting their labor agreements during the pandemic. He thinks it’s possible that teachers will strike or take other labor action, but said they may not find the same kind of public support for their activism as they have in recent years.

“After distance learning in the spring, a schooling disruption as a result of a teacher labor action would likely play different,” Marianno said. “How that would look in a case where parents are struggling with what distance learning looks like, in a case where school budgets are already strained by economic shutdowns — it’s risky.”

This is something usually vocal unions, like the Chicago Teachers Union, appear to be keeping in mind. Last week, the Chicago union took an informal telephone poll of members to gauge how they felt about launching a public campaign over teacher safety. The union’s president, Jesse Sharkey, said while a teachers strike is something the union would consider, it would try other measures first, like reaching out to parents and the press, and holding demonstrations, as it did before striking for 11 days this fall.

The city’s parents “are dealing with job loss, evictions, a lot of issues,” Sharkey told union members in a call last week. “Going straight to a line of ‘We have our demands and we’ll strike if we don’t get them’ is probably going to be hard for people to hear.”

In New York City, teachers union officials are threading the same needle. The head of the union, Michael Mulgrew, has generally expressed support for the school district’s reopening plan, which looks similar to Chicago’s, though he told WNYC recently that the union would draw the line if schools didn’t end up with appropriate safety measures.

These questions are especially relevant in Chicago and New York, which were the only two of the 10 largest school districts last week where average daily infection rates were 5% or lower, a public health threshold that many school districts are considering when making their reopening plans, the New York Times reported.

Neither city has told educators much about what specifically lies ahead: who will teach what and where, what kinds of protective equipment they will be provided, and what class sizes might look like.

In other school districts, as teachers have seen the details of plans, concerns have followed.

In Loudoun County, Virginia, for example, incoming teachers union president Sandy Sullivan said some teachers were willing to sign up for the hybrid model but changed their minds when they learned more about how often the district planned to clean buses and student desks. A district survey released Friday showed that about 46% of teachers wanted a fully remote start to the school year, as did the parents of just over half of students.

In Nevada, Marie Neisess, the incoming president of the Clark County Education Association, the largest teachers union representing Las Vegas-area teachers, said specialists like music and art teachers didn’t think it was fair that they would be expected to rotate through multiple classrooms to cover other teachers’ lunch periods, exposing them to more students and more risk.

Marianno, of the University of Nevada, says tensions may flare this fall as teachers unions and school districts try to come to an agreement about what their work days will look like at a time of great budget uncertainty.

An earlier wave of coronavirus relief money has given school districts money to help cover costs like protective equipment for teachers. And while it seems likely there will be more federal money coming to help schools cope with the coronavirus, it’s unclear how much, and whether it will offset state-level cuts to education now or in the future.

“It’s like we’re in a hold pattern,” said Neisess. “We have a plan ready to go, but it requires funding.”

Some of the go-to tactics of organized labor, though, would be harder to use in a pandemic. Rallies and sit-ins, though not impossible to hold, would need to be socially distanced. Holding a “sickout” is hard when teachers are worried they may need those days if they or their family members contract the virus. Asking teachers to work the exact number of hours in their contract is also difficult to pull off when teacher schedules have been upended.

Parent sentiment could also have a dramatic impact on the potential for labor action.

Right now, several national polls show that many parents, especially Black and Hispanic parents, are concerned about sending their children back into school buildings. But if sentiment swings the other way, it could be harder for teachers unions to continue to advocate for all-remote instruction, which rolled out with massive inequities in the spring, often shortchanging low-income students of color.

Some teachers unions are working hard not to alienate the low-income and working-class parents that have often been their allies in labor fights.

Last week, the Chicago union’s vice president, Stacy Davis Gates, said “if this becomes a fight to withhold labor,” that fight would have to include demands to improve conditions in local communities, a strategy known as “common good bargaining.” Already, the Chicago and Los Angeles teachers unions have included eviction protections and financial support for undocumented families in their lists of what it would take to reopen schools.

“This is not just about how many face coverings we can have,” Davis Gates said.