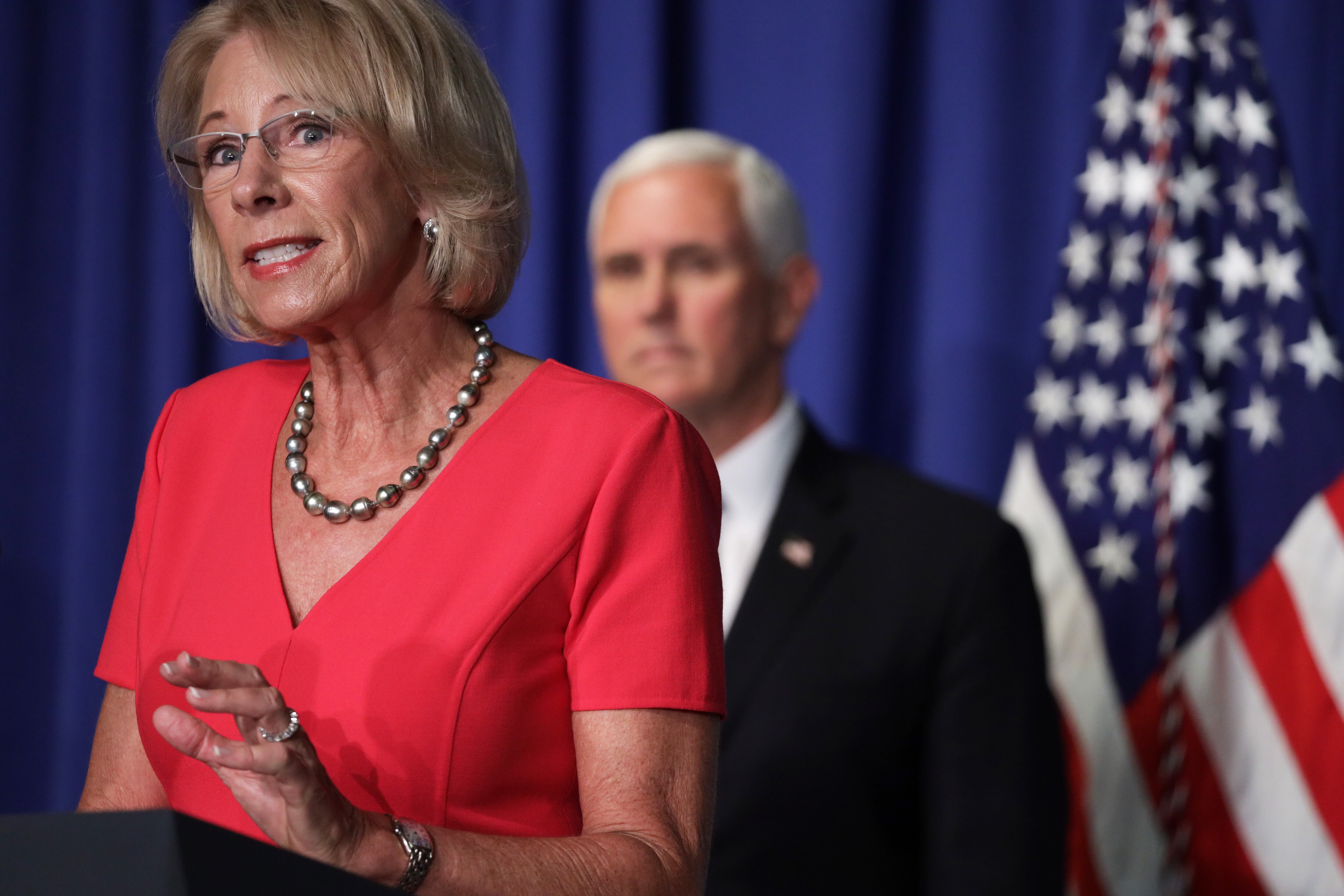

Education Secretary Betsy DeVos has pushed schools to reopen full time in the fall, castigating districts that have adopted a rotating two-day-a-week schedule and suggesting that there is little public health risk to opening up schools.

“There is no excuse for schools not to reopen again and for kids to be able to learn again full time,” DeVos said earlier this week on Fox News. “The data doesn’t suggest anything different.”

But her own department recently funded and released a report suggesting that a reopening plan in which students attended school in person only a few times a week could come with significant public health benefits.

“Dividing students into smaller groups, each of which comes to school only 20 to 40 percent of total school days, is likely to substantially slow the rate of infection spread, on average, compared to having all students attend school every day,” concluded the report, which was prepared for the Pennsylvania Department of Education and published by the U.S. Department of Education’s research arm late last month.

The analysis itself comes with a host of caveats. But it highlights that the federal messaging on the public health considerations for reopening schools has been far from clear, and underscores the difficult spot local school officials are in as they sort through differing expert opinions and try to avoid political controversy.

William Hite, the superintendent in Philadelphia, which has not yet released a full reopening plan yet, said Thursday he had found the Pennsylvania report informative. The district has been weighing it alongside other opinions about the safest way to open schools, while trying to ignore President Trump’s rhetoric, he said.

“It creates unnecessary confusion for the public when we are working like crazy to come up with these plans. And not just here in Philadelphia — across the country,” Hite said. “And then you have a person that says, ‘Hey, just bring everybody back,’ not understanding the breadth and depth of what needs to happen in order to do that.”

A spokesperson for DeVos, who has threatened to withhold federal funding from schools that don’t fully reopen, did not respond to a request for comment.

The report was designed to assess the risks of varying school reopening scenarios, using existing national and international data on the spread of COVID-19. Researchers accounted for the fact that children appear to be infected and spread the disease at a lower rate than adults.

Then they ran statistical models meant to estimate disease spread based on likely interactions between students and staff during the school day. First they compared a full five-day-a-week reopening without precautions to that schedule with additional safety measures, like having staffers wear masks, having students eat lunch in class, and adopting block scheduling. Those strategies were estimated to help limit the spread somewhat.

Then researchers looked at a more far-reaching approach: breaking students up into groups, with each group coming into school physically only once or twice a week. Because this allowed for more physical distancing and reduced contact among students, the researchers estimated that this was several times more effective at stopping the spread of potential infections than a full reopening, even with precautions.

“There’s a pretty big difference between the strategies that just try to manage things in the school but bring all the kids back every day ... versus the ones that divide the kids into smaller groups each of which attends part time,” said Brian Gill, one of the authors of the study and a senior fellow at the research firm Mathematica.

These results have been disseminated to school leaders Pennsylvania, and used to suggest keeping some students home. ”Schools should contemplate some reduction in overall student presence each day,” the state’s Education Secretary Pedro A. Rivera said in a message about the study.

Although the analysis was focused on Pennsylvania, the findings have broad relevance for districts wrestling with whether to bring students back in person full or part time.

A number of districts, including New York City and Fairfax County, Virginia have said students will return a few days a week, in large part to comply with existing guidance from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention that says students should stay six feet apart whenever possible. But DeVos and the Trump administration have been highly critical of this strategy, with Trump even criticizing the CDC, which is part of his own administration.

Whether or not the analysis holds up will depend on if the assumptions embedded in its models are correct. Alicia Riley, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California San Francisco who reviewed the report, emphasized this point. “These results are very sensitive to model assumptions and their applicability to real life will depend on the local COVID-19 situation on any given day,” she said.

Gill agreed, and the study frequently acknowledges that. “There’s so much that is still unclear about the science of the pandemic and about the infectiousness of kids,” said Gill.

As it has pushed for full reopening of schools, the Trump administration has emphasized the already steep costs of building closures: widely expected learning loss, students’ loss of social connections, even missed cases of child maltreatment. Those concerns are shared by many parents, educators, and doctors, as well.

“Physical health and safety are factors. So is mental health. So is social emotional development,” said DeVos. “And importantly, so are lost opportunities for students, particularly the most vulnerable among us.”

But rising case numbers are likely to complicate those plans. Even Trump administration officials have acknowledged that conditions vary nationwide, and schools might have to close if there are flare-ups in specific areas.

Gill said that his analysis shows how a staggered schedule for students might help avoid full closures.

“There’s a general recognition that there will be times when schools have to close down temporarily as a result of outbreaks in the school,” he said. “This modeling suggests you’ll likely have fewer of those and they’ll be farther between if you’ve got the students divided into these smaller groups attending part time.”

Texas and Florida have seen rising caseloads, but state education agencies have still pushed public schools to offer daily in-person instruction to all students who choose to attend.

The Pennsylvania study notes that it does not reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of Education, and Gill said no top officials there had reached out to him to discuss the report’s findings.

This all adds up to a confusing picture for school officials like Hite of Philadelphia. “We have a responsibility to ensure that children, staff members, and all else who work in our schools are safe,” he said. “Safety and science will guide our decisions about when and how we bring children back.”

But following the science is not always straightforward, Hite acknowledged. “Some of the guidance has been conflicting,” he said.