With talks over a new coronavirus relief package now stalled, Congress has not only failed to provide more money to schools, but also injected additional uncertainty into an already tumultuous school year.

The consequences will be far-reaching, for America’s schools and the over 50 million students they serve.

For Sharon Contreras, the superintendent of Guilford County schools in North Carolina, that means she’s scouring her budget for ways to pay for HVAC system upgrades, extra buses, and additional custodians.

“We’re taking resources that would have provided children opportunities ... and we’re now funding some basic health and safety issues,” she said. Without additional federal money, she said, future cuts could mean fewer art programs, school counselors, or even teachers.

“The lack of funds, when you look at all of the issues, it just compounds historic inequities,” she said. When she heard the Senate had adjourned, she said, “I was deeply disappointed.”

Across the country, school leaders are grappling with the costs of reopening schools safely, possible budget cuts from states, and no guarantee that additional federal help is coming. And the more uncertainty districts face, the less able they are to craft accurate budgets, making disruptive mid-year cuts more likely.

“I’ve been doing this work now for 20 years and I’ve never seen anything like this,” said Jonathan Travers of the nonprofit consulting firm Education Resource Strategies, which works with many school districts on budgeting. “The thing that is just so unique is the uncertainty.”

And even in districts that haven’t faced cuts yet, officials warn that they could come if the federal government doesn’t act. “I feel like we’re holding things together,” said Derek Richey, the chief financial officer for Cleveland’s public schools. “I don’t want to give the illusion that we can do that forever.”

Schools’ unprecedented budget uncertainty makes planning difficult

School funding is sometimes compared to a layer cake. Right now, school budgets are made up of many shaky layers.

First, there are no answers about potential federal relief money, for schools or for the state governments that fund schools. Talks broke earlier this month, and it’s unlikely that any deal will be reached before September.

Second, there is uncertainty around state money. Some states, including North Carolina, have not passed a budget for the year. Other states, like New York, have warned that they could go back and cut school district budgets if federal money doesn’t come through.

“We think there is a bunch more information on revenue — largely revenue takebacks — that just hasn’t been communicated to districts yet,” said Travers.

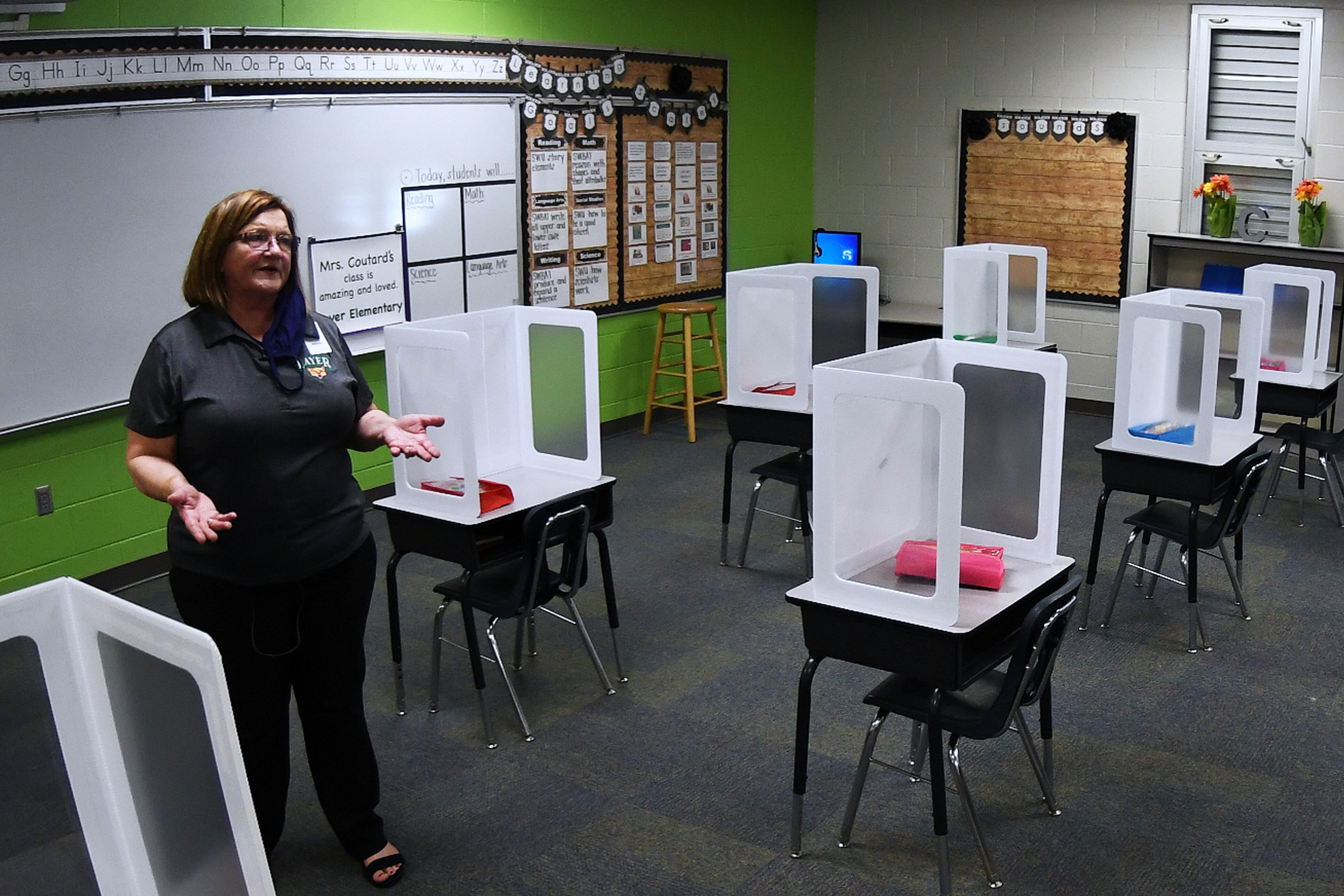

Third, schools don’t yet know exactly what this year will cost. Schools are still deciding how they’ll be providing education — remote, in-person or some combination — for most of the year, and those options could have different costs.

All told, district leaders don’t know how much money they’re getting, and they also don’t know how much they will really need.

Research shows this could drag down student learning. One Ohio study found that when district budgets were subject to more uncertainty, student achievement declined, likely due to increased teacher turnover.

Some districts are making preemptive cuts, while others wait and watch

In Denver, the district and teachers union agreed to reduce, but not eliminate, previously agreed-upon raises. In Portland, Oregon, the school district furloughed staff, including teachers, one day a week to save money.

Nationally, nearly 500,000 public school staffers lost their jobs or had been furloughed by mid-April as schools transitioned to remote instruction.

But Travers said he hasn’t seen many districts take other cost-cutting measures, like freezing salaries. “The thing that we’re seeing so far is the absence of agreements to increase,” he said.

Some argue that districts should aggressively reduce spending, particularly since fewer people leave their jobs during a recession. “We’re watching districts give teachers raises this year,” said Marguerite Roza, director of the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University. “It’s like spending money for a job you haven’t gotten yet.”

Districts that are starting the school year remotely could also save money by furloughing staff, like bus drivers, who can’t do their regular jobs while students aren’t in school. But many officials are reluctant to do so.

“As we start to reopen, we’re not going to need all of our employees — we’re going to need extra employees,” said Richard Barrera, vice president of the school board for San Diego Unified, which plans to start the year remotely. “School districts can’t just turn on a dime and lay people off and hire them back up.”

Economists also warn that these sorts of job losses from schools can drag down local economies.

Contreras, whose North Carolina district is also starting the year remotely, said that furloughs would hurt the districts’ most vulnerable workers and the community at large. Staff most likely to be furloughed — like bus drivers and school nutrition workers — are disproportionately people of color, she said.

“We’ve made every attempt not to furlough staff because it disproportionately negatively impacts our community of color in Guilford County,” she said.

So what happens if no federal money comes through? School reopening challenges, layoffs, and long-term pain for schools

To a person, district officials insist that CARES Act dollars — over $13 billion for schools — won’t be enough to pay for new costs districts have incurred, much less make up for state budget cuts.

In Cleveland, Richey said a hybrid model where students learn in school buildings a few days each week would cost an extra $20 to 30 million above what the federal government has provided. The district is starting the year remotely, but Richey said he expects it will transition to a hybrid setup eventually.

“We need some additional assistance, likely federal assistance, because our reopening costs are just going to cost more than we were provided in the CARES Act,” he said.

If that money doesn’t come through, some district leaders worry that school buildings will remain closed longer than necessary. “That will certainly delay our ability to physically reopen even when the conditions of the virus have gotten to the point where we think it could be safe,” said San Diego’s Berrara.

No federal money could also mean layoffs of teachers and other staff, since personnel accounts for the largest share of district budgets. Those layoffs may come in the middle of this school year or next year, depending on the state and district’s particular situation.

One analysis found that if state budgets fall by 10% — a plausible estimate — and no new federal funding comes through, schools would end up with $400 less per student. Those sorts of budget cuts could translate into hundreds of thousands of laid-off teachers.

The worst hit may come in a year or two. During the last recession, it took school budgets years to recover from the downturn.

Whether the same thing will happen again depends on how the economy recovers and how policymakers respond. For now, some states are using one-time budget tricks — like tapping into reserves or delaying payments to school districts — that they’ll have to pay for down the line.

All said, research suggests that spending cuts will translate into more learning loss, and making it harder for schools to help make up for students’ struggles during remote instruction.

“How do we ensure that learning loss is mitigated?” said Contreras. “We can’t. We don’t know if we can offer tutoring programs, if we can offer summer programs.”