Chivon Gulley is getting ready for a very different first day of school.

When the pandemic hit this spring, the Oklahoma City public high school science teacher focused on helping students with failing grades bring those averages up. She checked in with families twice a week and held office hours, but never taught live on video.

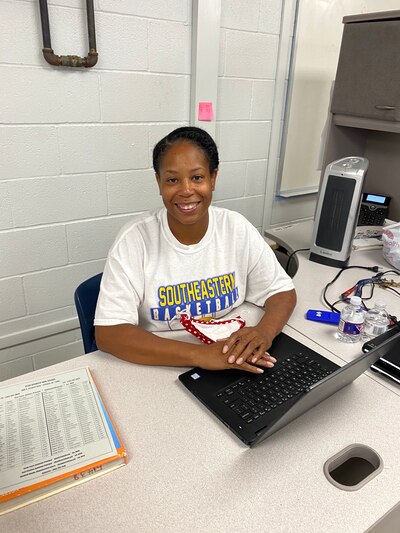

That’s all about to change. Starting Monday, she’s teaching seven classes virtually, mostly biology and human anatomy. She’ll be armed with over a month’s worth of virtual teacher training. And she’ll be set up in her lab at school, model skeletons and all.

But even though she’s been doing test runs with colleagues, Gulley — who’s known for “coaching” her students like she does her basketball players — hasn’t been able to completely banish the anxious thoughts. What will she do if a student’s internet goes down? If no one can hear her?

“It’s an uncomfortable thing because we’ve not done it before,” she said. “I am a little nervous to see: Did I do it right?”

As Gulley tries to pull off virtual science experiments with her students, she’ll be part of a national experiment herself — testing whether it’s possible to roughly replicate a regular school day online.

This spring, high-poverty school districts like Oklahoma City were less likely than more affluent districts to have offered live virtual classes for younger students, and less likely to have offered lots of live virtual support from teachers for students of all ages. Those districts are also more likely to be all-online this fall, according to a recent analysis from the Center on Reinventing Public Education. So for many of those educators, this fall marks more of a first than a second attempt at fully virtual teaching.

These are also the same educators whose students are more likely to still be facing many of the same obstacles from the spring, including caring for siblings while their parents work outside the home. All of that makes their jobs especially complicated this year — with a lot riding on how they do.

“It is just an extraordinarily challenging set of circumstances,” said Bob Pianta, the dean of the University of Virginia’s Curry School of Education and Human Development.

“This is all new territory,” Pianta said, pointing out that teachers are learning everything from new digital tools to how to set up their online classroom. “You have to learn the nuts and bolts of those components and put them together before you even get to the practice.”

What’s different now?

Researchers have found that, in general, students in high-poverty school districts were asked to do less schoolwork and spent less time in class than their more affluent peers this spring, and were more likely to review old content than to learn new concepts.

In many cases, students lacked access to devices or the internet at home. School officials were often hesitant to require attendance and grade assignments when they knew students were caring for younger students or working to support their families. And teachers didn’t always have the training or materials they needed to make the transition.

In school districts like Oklahoma City, Baltimore, Detroit, Chicago, Los Angeles, and San Diego, some teachers met with students over video, but many relied heavily on things like paper work packets or online activities, and regular live virtual instruction wasn’t expected.

This fall, many of those school districts are setting very different expectations. Often, they are requiring several hours of live virtual instruction each day and setting up regular class schedules. Many are also returning to normal grading and attendance policies.

That’s the case in Baltimore, where most elementary school students will receive just under four hours of live virtual instruction a day, while high schoolers will get around five and a half hours — in addition to virtual small-group work and assignments students will complete on their own.

Some are skeptical that all of that “live” time makes sense, especially for young students. But the district’s CEO, Sonja Brookins Santelises, said students told the district they wanted more of a connection with their teachers. Even her own daughter, a student in the district, complained about how school worked this spring.

“She said to me, ‘Really, mom? You guys really think just posting assignments is teaching?’” Santelises said. “We heard that over and over again.”

Santelises said her schools, which serve 80,000 mostly Black and Latino students from low-income families, also have academic ground to make up. So the district is trying to send a clear message now that “we are open for learning.”

“We are not engaging in a choice between whether we’re attending to the social-emotional needs of young people, whether we are acknowledging their trauma, or we’re going to educate them and make sure that they have the academic skills that they need,” she said.

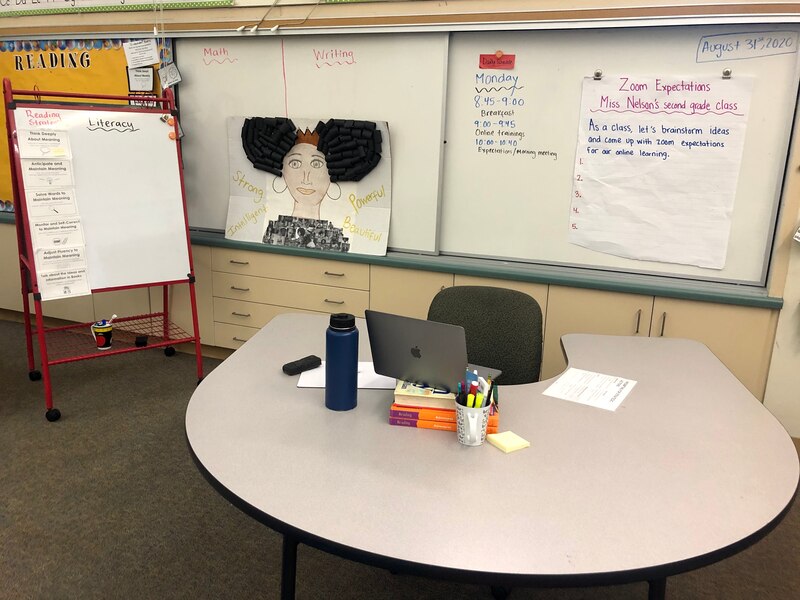

The shift to much more live instruction will be a big one for educators nationwide. In San Diego, second-grade teacher Bree Nelson offered 45-minute check-ins on Zoom a few times a week last year, but is now set to provide four hours of live teaching daily. Her big challenge will be making sure class doesn’t feel robotic — she doesn’t want to feel like she is “lecturing literally 7-year-olds” — without any of her normal tactics, like rearranging students into small groups if they’re struggling on their own.

But there are several things working in these teachers’ favor. Technology access for students has improved, as districts have purchased tens of thousands of computers and wireless hotspots and helped more families get hooked up with low-cost or free internet.

For Carrie Russell, a high school math and computer science teacher in Detroit — where schools are still set to open in-person but many students will remain remote — that means grading assignments should be simpler. This spring, students without reliable internet completed assignments on their phones and texted her pictures of their work.

“I heard a lot of teachers say that their necks got kinks in them because they’d get these messages and try to read someone’s notebook,” she said. Now, every student in Detroit Public Schools will have access to a device and six months of a hotspot.

Students and parents also will be more familiar with how to navigate online programs. And some places, like Oklahoma City and Baltimore, pushed back the start of the school year to add planning time.

Several teachers said they thought higher standards for grading and attendance would be helpful, too.

In Oklahoma City, Gulley said many students checked out when they found out they weren’t being graded. “It made me crazy,” she said. Some of the basketball players she coaches were surprised to realize they needed to scale back their work hours to accommodate a more normal school schedule this fall.

“They’re like, ‘Wait a minute, so we’re going to have to be in class?’” Gulley said. “And I’m like, ‘Yes, it’s not going to be loosey goosey like it was in the spring.’”

And they have experience to draw on. Many teachers in high-poverty school districts said they’re used to filling in big gaps in student learning and helping students cope with trauma and other emotional needs.

“I have so many of my students who lose those chunks of time anyway,” Russell said. “They move, they get kicked out of school for discipline reasons, they have to stay home and take care of a sibling, or a parent gets sick. We’re also used to our kids being two to three grade levels behind, so you’re always trying to find ways to plug holes.”

Some challenges persist

Still, this group of teachers has to contend with some big challenges, including helping students navigate many of the same obstacles that tripped them up this spring.

Several teachers said their summer training was packed so close to the start of the school year that it left them little time to practice, or was so voluminous that it became overwhelming.

Gulley said she appreciated the all-hands-on-deck effort her school district put forth to make sure teachers were prepared for their virtual classrooms, though it meant many long days of planning and training.

“We are very much mentally exhausted,” said Gulley, in Oklahoma City. “If I were a pitcher, the water is flowing over.”

Students’ home lives haven’t changed much. And many teachers will still have their own children to worry about — and this year, those kids, too, might be expected to attend more live classes and require more parental support.

Rita Jackson, a fourth-grade teacher in Baltimore, will have her own 9-year-old daughter in her class, and be caring for a “rambunctious” 3-year-old.

“It’s a lot of unknown,” she said. “What if there’s a potty emergency and I’m in the middle of this required 60-minute synchronous section with my students?”

Teachers also knew their students by the time the school year was upended last year. This year, they’re building relationships with students and parents from scratch, virtually. For that reason, several districts are asking teachers to spend extra time in the first week orienting students and parents and resetting expectations.

But it’s unclear, in many cases, what districts will do if large numbers of students don’t show up or if there is a big dropoff in engagement.

“We’re all, at least in my building, trying to shorten the time we really talk at them,” said Telannia Norfar, a high school math teacher in Oklahoma City who has trained other teachers through the local union. “Turn off your screen, go do some work, come back the last five minutes, and let’s talk. I’m hoping that will help.”

Santelises, the Baltimore schools CEO, said she doesn’t want to be inflexible — already, teachers in her district are planning to record a lot of the lessons for high school students who they know will be working because their families are “under financial strain.” And they’ve set aside parts of the day to focus on small-group work or offer time for advising.

But Santelises also doesn’t want to expect too little of students. She took issue with an earlier district plan that would have offered students only 75 minutes a day of live virtual instruction.

She thinks teachers in her district are up to the challenge. Figuring out how to make it all work is now up to educators like Jackson.

“I think that it’s going to be hard, I think it is going to be frustrating,” Jackson said. “But I think that it is doable.”

Eleanore Catolico contributed reporting.

This story was updated on Wednesday, September 2, to include additional information about Oklahoma City’s training for teachers.