Once again, a justice system declined to bring charges against police officers in the killing of a Black American. Once again, demonstrators took to the streets to protest. Once again, a sense of hopelessness hung over communities.

And once again, as one Tennessee educator told us on Thursday, school staff must still “get up and teach and act as if none of yesterday happened.”

Throughout this tumultuous year, Chalkbeat has sought to lift up the voices of students and educators as the nation has reckoned with police violence, justice, and racism in America.

We have turned our website over to students, asked teachers how they’ve facilitated tough conversations and supported their students experiencing trauma, and documented how this moment has led to meaningful change about what and how students are taught.

After a Kentucky grand jury this week chose not to charge any police officers with killing Breonna Taylor in her Louisville apartment, Chalkbeat asked students and educators across the country to reflect. We returned to people we’d heard from earlier this year, to see how they are processing the Taylor decision after a summer of tragedy and activism.

We wanted to understand how educators interacted with their students — now back in class trying to navigate all the difficulties of pandemic education — and how they planned to keep issues of racial justice in the public consciousness.

Here are their reflections, in their own words.

Andrea Castellano

Teacher, third grade gifted & talented, Brooklyn Landmark Elementary, New York

We did not do our [English Language Arts] lesson this morning. Instead, we talked about who Breonna Taylor was, what her dreams were, and why people are out in the streets protesting. We learned about the origins and goals of the Black Lives Matter movement. My 8-year old students told me what they knew about police brutality and the murdering of Black people. They expressed their sense of outrage at the injustice and explained that it needs to stop. They didn’t know about the grand jury decision, but they definitely knew what racism is.

As their teacher, I had to walk the line between informing and overwhelming. It’s not always possible to end on a positive note when discussing something deeply tragic and unjust, but it’s always appropriate to affirm the intrinsic value of human life. With that in mind, we spent the morning exploring our identities with an emphasis on how our values and beliefs inform our decisions.

My students, like so many, are disappointed, angry, upset, fearful, and saddened. But my school has always done well in acknowledging the emotional weight of racism on our children while also creating opportunities for activism. We will continue to find ways to resist and uplift Black voices, whether in the streets, in school or at home. We are waiting for America to be the country we want it to be. We write, we share, we dialogue, we protest, we pray, we hope, we wait, and we always try again.

Lamont Satchel Jr.

Senior, Cass Technical High School, Detroit, aspiring lawyer

It boils down to, just, why? Breonna Taylor was sleeping. As a young black man, it hurts because my future is unknown. I have so many things that I want to do. But it can all be shut down in the blink of an eye … Last time I checked there’s no law against sleeping. We’re looking at the news and looking at what’s going on and asking, “Am I going to be next? Am I going to be the next hashtag, the next shirt, the next protest chant?”

Tavara Tucker

Fifth and sixth grade math teacher, Tindley Summit Academy, Indianapolis

My heart is heavy. What happened to Ms. Taylor could have happened anywhere. I educated brown-skin children who don’t understand and all they do understand is that she was in her home and her life was taken. This scares them and as an educator it is my duty to make sure my brown-skin babies know and understand that it is all our duty to protect and stand for what is right for all injustices. As an educator how does this affect my teaching — my scholars see and hear people who look just like them dying. This is trauma on top of trauma for them: to watch, learn, and witness those who look like them die at an alarming rate says to my babies, “we are disposable.” It is my duty and divine purpose to educate my brown-skin babies and those who are our counterparts that we are not disposable, but that we are intelligent, educated, strong, beautiful kings and queens who bring just as much value to this world as the next.

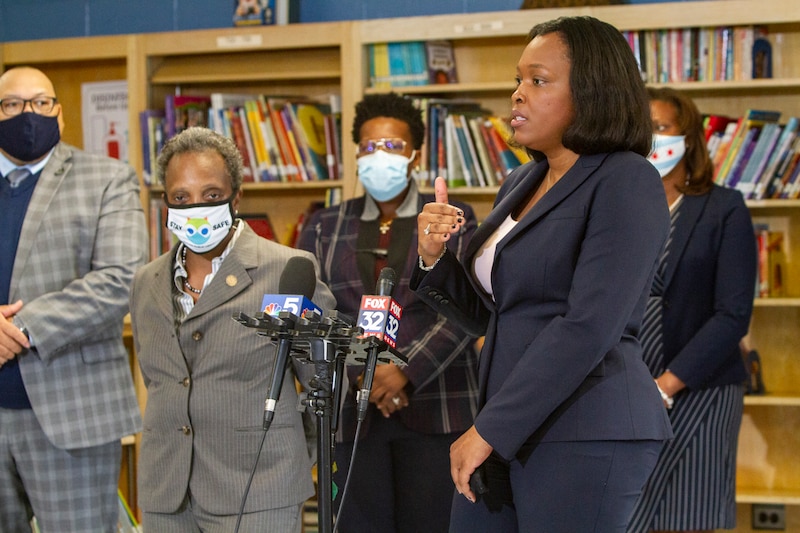

Janice Jackson

CEO, Chicago Public Schools

As a district, we affirm that Black lives matter and encourage our school communities to continue having constructive conversations. Whether instruction is in person or virtual, our schools must be spaces where our children can have honest and productive conversations about racial injustice and our role in fighting systemic racism. The Say Their Names toolkit that we released in June has resources to support students and help us all engage in restorative, anti-racist modes of thinking. I hope that we can take the next few days to check in on each other — especially our students — and be understanding about how the news might be affecting them emotionally. It is yet another reminder that our children are growing up in an imperfect world, and we all have a role to play in making it safer, more just, and equitable for all.

Meril Mousoom

Senior, Stuyvesant High School, New York City, activist with school integration group Teens Take Charge

I was a chant leader on the 77th anniversary of the March on Washington because I saw that no one else was doing it. And I just started screaming, “Say her name.” And everyone said Breonna Taylor. All the people were marching, we were from all over America and lived very different lives, but we were all together, thousands of people, trying to get justice for her. But then yesterday I saw so many videos of protesters getting run over by a car and arrested violently. One of the women the police pinned to the ground was two months pregnant. I was just so devastated at the lack of humanity. Our way of coming together, or grieving her death, was taken away from us. It feels like the end of the world because I know that Black people in this country are not seen as human. And as a South Asian I am realizing all the oppression I have faced stems from that. I am still crying. I do not know when, or if, I will feel better. I have planned so many marches throughout the city and I want to scream.

Ashley Farris

A.P. language and composition teacher, KIPP Denver Collegiate High School

I always encourage my students to interact with our democracy by asking questions, searching for truth, and being critical of our institutions and systems in order to continuously improve our society. Every year we do a unit on the U.S. justice system in which I ask students to explore what justice means to them and whether or not they see that reflected in our society. In the wake of cases like George Floyd, Elijah McClain, and Breonna Taylor, I know that unit is more important than ever. As a teacher of color, teaching students of color, I want them to know that their lives matter. My goal has always been for my students to leave my class with the confidence to express their opinions and an ability to form a strong argument. My course teaches argument and rhetoric, but the enduring and underlying understanding is providing the tools students need to be the change they want to see.

Taylor Jackson

Tenth grader, KIPP Indy Legacy High, Indianapolis

Honestly, I feel scared because Black women live in a world where they’re not even protected by Black men. I feel as if it is hard growing up as a Black woman, even around Black women. We are disrespected by each other, we’re disrespected by Black men, we’re disrespected by white men and women. I mean it’s like it’s not safe for Black women because we’re not even protected by our own people. I heard about [the grand jury decision] through social media. It made me feel mad because it’s stupid for them to even question the officers being charged, like they went into somebody’s house and killed them. I feel if it was a white woman, they would have charged them, this would have been over. All of it wouldn’t have been a discussion. They should have been charged with that.

Rashid Johnson

Director of school support for the Achievement Network, Brooklyn, New York

As a parent and educator, I feel a sense of paralysis and distrust in America’s racist, one-sided legal and justice systems for Black people. Black lives in America, for centuries, have been a superficial spectacle feeding racists’ appetites for death and pain. That’s how I feel.

Zaniyyah Jacobs-Wright

Freshman, Rutgers University-Newark

I found out about the verdict on Twitter. When I read it, I just burst into tears. I couldn’t stop crying, my heart was breaking. After I calmed down, I honestly wasn’t surprised. As a Black woman in this country I’ve never felt like the judicial system cared about us. I’m 19 and I’ve seen way too many instances of Black and brown people being killed and there being no justice for them and their families. It still hurts me to see that either there is no progress, or it’s happening so slow that it’s basically microscopic. I would love to see actual progress. But do I think it’s going to happen over night? Definitely not.

Breanna Collazo

Sixth grader, Mott Hall V in the Bronx, New York, leader of a Black Lives Matter march

I’m feeling just very strongly about their decision. I’m really mad. I’m very disappointed. I’m sad and I feel like there’s nothing in this entire world that makes sense why she does not get justice but somehow other people do. It does not make sense to me … I definitely will start going to more marches and stuff like that. I truly want to say something. Because mentally I’ve been judging a lot of people. I’ve been judging the president. I’ve been judging the judges themselves. I have been judging the people who actually made these decisions. Right now this just really is so unfair and unjust. Also considering that other people in the Black community have faced this injustice, and still they have not gotten justice ... it’s just so hurtful.

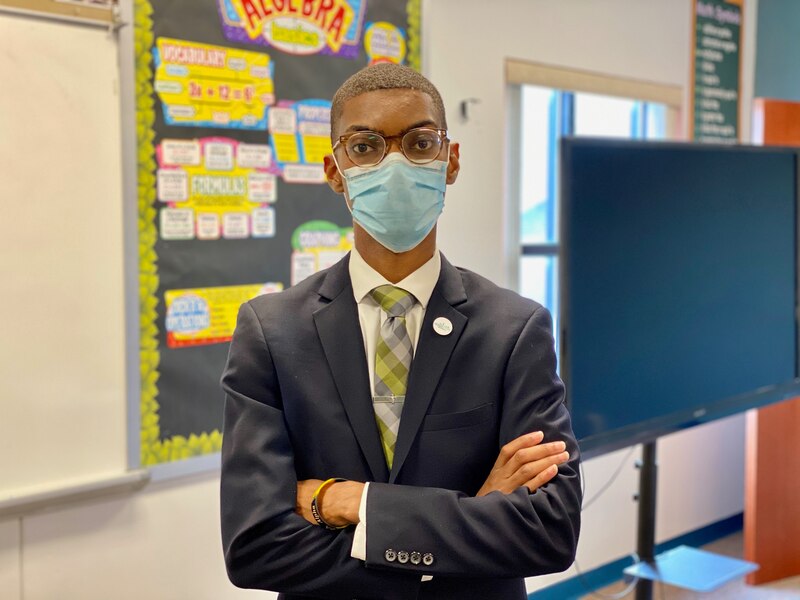

Marcus Handy

Ninth grade algebra teacher, Rooted School, Indianapolis

The decision was scheduled to be announced at 1:30 p.m, and I was in class. My students were in the middle of an entrepreneurship project. I was at my desk, grading papers, getting my plans together. But the Breonna Taylor case was on my mind. Really the forefront of my mind, because I knew that decision was going to be announced and I had a feeling in my stomach that it was not going to be favorable.

The case hit close to home for me. I live in Indianapolis. Louisville is not very far away. I know people who live in the city, and Breonna Taylor is not very much older than I am. I remember being angry, and it wasn’t just because the officer got off. It was more the charge that they decided to give to the one officer … An apartment wall got more justice than a Black woman’s life.

I went to a township school here, Indianapolis, and that school had 4,000 students. [Township schools are in an outer, more suburban ring of Indianapolis]. If we came to school and talked to social issues, that could get very hostile, very quickly, because you have so many people on so many different ends of the spectrum. I remember distinctly going to school every day when Trayvon Martin was killed with my hoodie on. I remember going to school angry, because the classes that I was in, I was an honors student. AP student. I was usually one, maybe one of two, Black students in a class that had 25-30 kids. When I went to these spaces, that news didn’t affect them. In solidarity, I would wear hoodies to school.

I want to be ... that teacher that I maybe did not have, for my students. I want to be able to offer that space to students, and to let them vent and to talk to us.

Lisa Bennett

Teacher coach, Cordova High School, Memphis

There are times where I feel like I want to completely withdraw from my colleagues because it seems so hopeless. Sometimes I feel like in the busyness of the day that sometimes it’s like a temporary balm so you don’t feel so hopeless. I was talking this morning about having enough batteries for calculators for when we go back to school in person. Those kinds of things have to go on. I guess embedded in that is some sense of hope. Not necessarily feeling hopeful but continuing to tread on is its own hope. When you build up your hope that this time we’re going to do right by Black people, Black women, that this time we’re going to get it right because the world has seen what we’re doing is hurtful, harmful, and evil and then we don’t ... That is what I think what makes some of us feel hopeless. We look at each other and our babies and still say there is hope. We have to. We do get up and trudge through another day.

I do struggle as a Black woman in education. I struggle with the narratives, the stories that are in textbooks or educators’ mouths that continue to devalue the lives of Black folks. And not just here in the United States, but around the world and across the centuries. They portray us as commodities to be used and fault us for the harm committed against us. And that’s what they did with Breonna Taylor. They re-victimized her over and over again and somehow blamed her. And those who committed the violence were held harmless. And that’s in our textbooks and our curriculum. They say it’s unfortunate but perfectly legal that this woman was shot and killed in her sleep. We are going to have to learn better, do better, and be better. In curriculum, discipline, hiring. Until we focus intentionally on these issues there will be people who will think it was moral, ethical, and legal for someone to shoot her, a Black woman, in her bed. Someone was taught that.

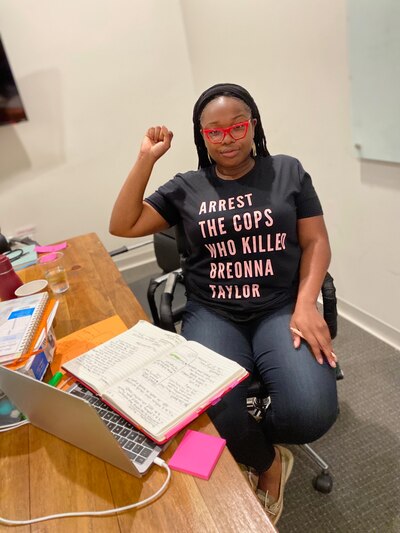

A’Dorian Murray-Thomas

Newark school board member, founder and CEO of SHE Wins Inc., which provides leadership and social action training to young women, particularly those affected by violence

To us, Black women in America, [Breonna Taylor’s] life matters. And we will always say her name.

Black America has proved time and time again that we can transform the pain from racism and repression into tools to disrupt the very systems hell-bent on our destruction. Today, our children remain more bold and courageous than ever. It is our duty to speak truth to power, march alongside them, and call them by their name — beautiful, capable, powerful, and loved.

We owe it to ourselves and our young people to hold space for both our rage and grief. From the classroom to the board room, young people must be empowered to speak truth to power, and be given the tools to challenge the status quo wherever they see it. They are more than our future. They’re our right now.

Melissa Collins

Second grade teacher, John P. Freeman K-8, Memphis, recent inductee to the National Teachers Hall of Fame

As the country continues to deal with systemic racism, we continue to discuss the injustices pertaining to police brutality, equity, and social justice among African Americans. As an educator, it is disheartening to hear about the injustice of Breonna Taylor. Constantly, I am reminded that race and poverty can impact how Blacks are treated in America. Therefore, I feel it is our obligation to equip students with the appropriate knowledge and disposition regarding race relations in this country. This year, I will continue to spark empathy, curiosity, and creativity among my students, so they can hopefully create change in America. I will talk to them about race and how they can advocate for change. Also, I will permit them to talk with their peers in other races and cultures so they can appreciate differences. If racism ends, it will take the future generation to stand up and seek the change that they want to see in the world.

Aniya Gordon-Ellis

Tenth grade student, Great Oaks Legacy Charter School, Newark

Dear Breonna Taylor,

I’m sorry. I’m sorry that the system you dedicated your life to has failed you, when you did not fail to show up everyday for it.

I’m sorry that the walls of your neighbor’s house were worth more than your life. I’m sorry that now, in your grave, people place blame on you just for sleeping.

I am angry and disappointed that your body was shot and left for dead, but they tended to the brick walls of the neighbor’s house as if they were wounded. We scream, “Black lives matter,” but too many of us stand by as Black women continue to be unprotected and disregarded.

I correct myself when I say that the system has failed you. No it hasn’t, it did just what it was built to do: protect one group of people while dehumanizing the other for the color of their skin.

Your mother couldn’t even speak after she heard the ruling. I’m torn because you left this world prematurely and left the people that loved you dearly, but you left a place where they did not value people that look like me and you. The officer was charged for all the bullets that missed but not the ones that took you from us. What does that say about America? Well I’ll leave that for the people to decide.

Nikia D. Garland

English teacher and adjunct professor, Indianapolis

I have been profoundly impacted by her death and the lack of justice. It is deeply disturbing to me as a human being to know that I live in a country that does not believe Black women are not worthy to even live. I am angry beyond what I can adequately articulate. We, Black women, have been sorely mistreated since the days of slavery. It is hard for me to believe that our lives matter. How could they in the face of such rancor and disdain? My students are almost immune to the racial disparity and strife that we face daily. It’s hard to teach under such circumstances.

I believe Malcolm X said it best: “The most disrespected woman in America is the Black woman. The most unprotected person in America is the Black woman. The most neglected person in America is the Black woman.”

I drove to Louisville a month ago just to see this mural. She could’ve been me. A relative. A student.

Yvonne Acey

Retired teacher, Memphis, community organizer who taught high school students during the civil rights movement and marched with Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis in 1968

It’s difficult when leaders don’t drive with justice in the front seat. It breeds distrust and lets us know we have a long way to go. We have come a long way in a sense, but not really. Racism is running wild, sexism is out of control. We are trying to keep hope alive. The decision with Breonna Taylor still lets me know that we as African-American women are facing brutality and injustice. As long as we can move around, we see symptoms of it. And I don’t know when it’s going to end. It makes it so hard to fight. We as African-American women are striving hard to keep hope alive and overcome. But we don’t get the credit and we don’t get the pay.

We have to let our students know that they too are Americans. They have a right to freedom, justice, and equality. To prepare them, they must know their history and be proud of their history. Time is neutral. It doesn’t fix things. But courage, determination, and perseverance from leaders change things. We can change. We have hope. We know the problems and at this point have developed some of the answers. We have what it takes.

The following Chalkbeat staff members contributed to this report: Koby Levin in Detroit, Christina Veiga in New York City, Caroline Bauman and Laura Faith Kebede in Memphis, Ann Schimke in Colorado, Aaricka Washington and Dylan Peers McCoy in Indianapolis, Patrick Wall in Newark, and Cassie Walker Burke in Chicago.