In 2001, during Miguel Cardona’s third year as a teacher, a Connecticut group invited a nationally known white supremacist to speak at a public library not far from his elementary school.

The event prompted anti-racist demonstrations that led to clashes with police. Cardona used news coverage of the event as the basis for a classroom discussion about prejudice, violence, and tolerance, and had his fourth graders write about it.

“Although these students may be at a very tender age, their maturity and ability to deal with issues such as these are qualities that Meriden should be proud of,” he wrote in his hometown’s newspaper, the Record-Journal, which published excerpts of his students’ work.

That Cardona felt comfortable leading that lesson two decades ago, when educators had significantly fewer resources to help them talk about racial justice, is “a foreshadowing of why he is in the position he’s in today,” said Orlando Valentin Jr., a fourth-grade teacher in Meriden. “I think it shows that he’s a trailblazer.”

It was one of many times Cardona would confront racism and deftly navigate difficult conversations as an educator in Meriden — a small city in Connecticut that has deeply shaped his thinking about education. If confirmed as the next education secretary, it will be those experiences he draws on to help schools address the growing educational inequities wrought by the pandemic and navigate the country’s ongoing racial reckoning.

“He is the secretary of education for this moment,” President Joe Biden said when he nominated the Connecticut schools chief last month. Biden’s transition team did not respond to a request to interview Cardona for this story.

Cardona grew up in public housing in Meriden, a city of about 60,000 located between Hartford and New Haven. His grandparents and parents moved to Meriden from Puerto Rico, and Cardona began school as an English learner, having learned Spanish as a child.

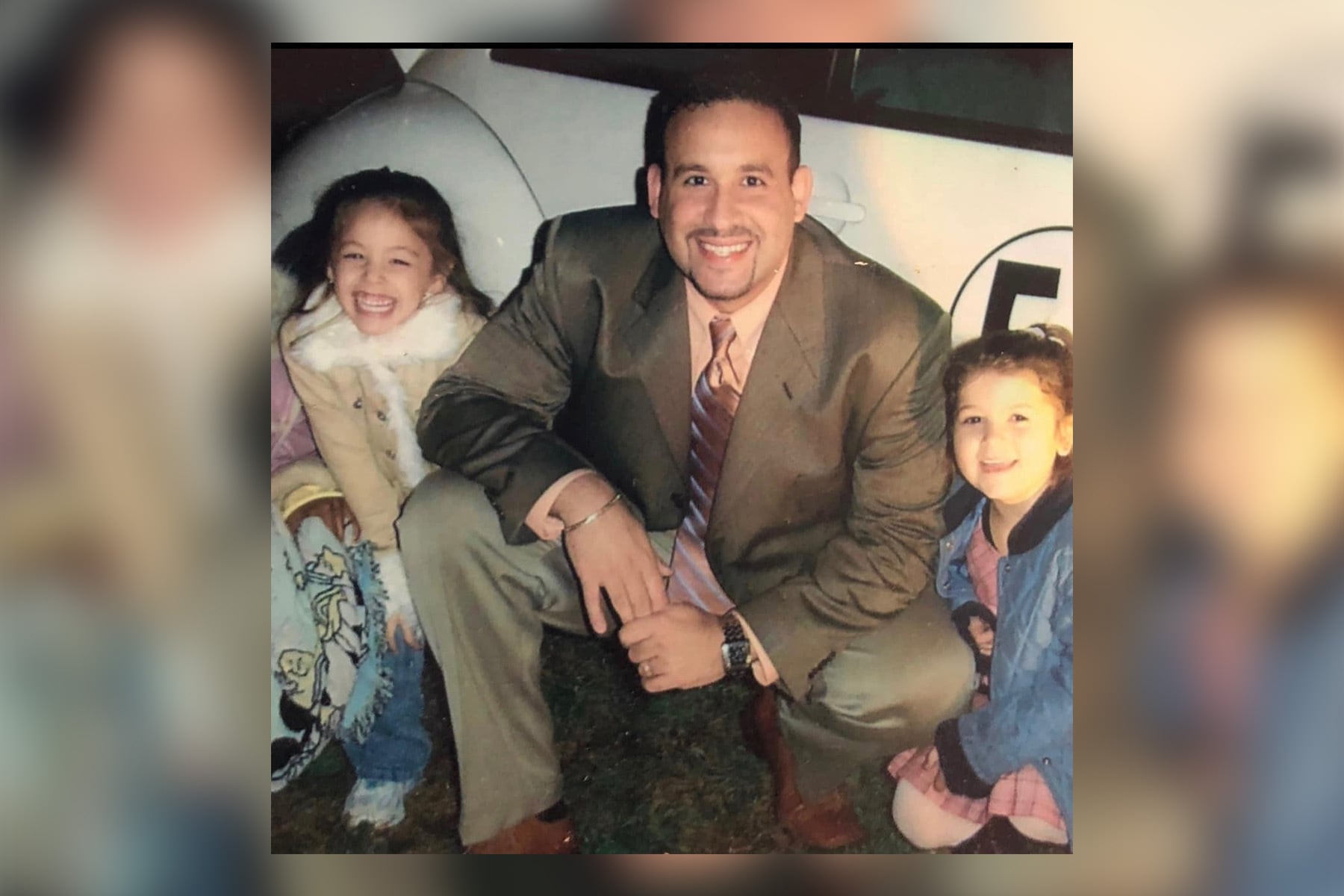

Cardona began teaching fourth grade at a Meriden elementary school in 1998, and within five years had become the youngest principal in Connecticut. At Hanover Elementary, he oversaw a period of academic growth and earned a reputation as a caring educator who helped create a community where families from different backgrounds felt genuinely welcome. That was particularly important at a time when the school — which had historically enrolled more white students and fewer students in poverty than other parts of the school district — saw a significant increase in the percentage of Latino students and students from low-income families.

Students, parents, and teachers recall that Cardona was always visiting classrooms and talking with students. It was like he didn’t even have an office, said Lauren Mancini-Averitt, a longtime Meriden teacher who heads the district’s teachers union. He followed students’ trajectories long after they left Hanover, sometimes writing their college recommendation letters.

“It was really personal. It felt like a family,” said Shawn Hutchins, a former Hanover parent who often participated in school events. That was especially meaningful to him, because “my kids were kind of like some of the early Black kids that actually went to the school,” he said. Cardona was “always asking: Is everything OK? Do you have any questions about anything?”

When Hutchins’ family twice had to move outside the school’s boundary due to their financial situation, Cardona helped them petition district officials to stay at the school so their daughters wouldn’t be uprooted from the community they knew. It was a “defining moment” in his family’s life, Hutchins said.

When the school hosted a spa night, Cardona jumped in and got a Paraffin wax treatment. At Bingo games, he called the numbers, recalled Gina Pellegrino, who served as the head of the school’s parent-teacher organization when Cardona was principal.

Her daughter Juliann Pellegrino, now 20, still remembers when Cardona visited her kindergarten classroom dressed as the conductor from “The Polar Express,” — and how excited he was for students to try different foods at the school’s multicultural night.

“He really tried to get us to embrace all these different cultures and have us recognize where everyone comes from,” she said. “It definitely had us open up our eyes a little bit, even at such a young age.”

A defining feature of Cardona’s leadership is the high expectations he has for students, especially English learners and students from disadvantaged backgrounds, several educators who’ve worked closely with him said.

To Cardona, it’s not “oh pobrecitos” — “oh poor them” — said Richard Gonzales, an associate professor in residence at the University of Connecticut’s Neag School of Education who has worked closely with Cardona on principal preparation initiatives. “No, no, no. We will serve them as well as possible, and we will ask them to do their part, and they will rise because they’re very capable.”

As an assistant superintendent in Meriden, Cardona pushed to remove prerequisites that had previously kept many low-income students from enrolling in Advanced Placement and early college classes, and let students decide if they were up to the task instead. He was also vocal about the need to hire a more racially and ethnically diverse staff, and flew to Puerto Rico to try to recruit more bilingual teachers.

As part of the district’s work to reduce suspensions and expulsions, Cardona was adamant that new school climate specialists should be able to speak students’ native languages or look like the students they were working with, recalls Superintendent Mark Benigni. Then Cardona personally helped recruit for those positions.

“The backdrop of all of this is, I think, Miguel is a public school advocate,” Benigni said, “and he wants to make sure public schools really are inclusive places for all kids.”

His first chance to take those ideas to a bigger audience came in 2010. Cardona, still the principal at Hanover, was tapped to co-chair a state task force charged with studying the academic gaps between Connecticut students of different racial and economic backgrounds.

The group was also expected to propose solutions — no small feat in a state with some of the worst disparities in the nation between students of color and white students, and more affluent students and students from low-income families, on “any benchmark that you can look at,” as Subira Gordon, the executive director of ConnCAN, an organization that advocates for educational equity in Connecticut, put it.

Gordon, who worked for the state legislature at the time, said Cardona drew attention to issues “that we think are second nature” in Connecticut now, but weren’t yet on state officials’ radar.

He zeroed in on factors that could affect student achievement that went beyond what happened in school, like housing inequities and children not having access to fresh food, Gordon said. He was early to focus on disparities in school-based arrests and chronic absenteeism, and the importance of family engagement and wraparound services. And he made a concerted effort to make sure concerns he heard from communities of color throughout the state were reflected in the task force’s reports.

“It was just honest,” Gonzales said. “Flat-out naming the issues of groups being under-served … Flat-out saying: We are neglecting our responsibilities.”

Students just saw a capable leader who they could trust with difficult conversations, including ones about race and racism.

Juliann Pellegrino recalls that when two of her white high school classmates posted a video online that included an anti-Black racial slur, she visited Cardona, then Meriden’s assistant superintendent, to talk. The video attracted a lot of attention in the community, and the two students had to address the school and apologize.

Pellegrino explained to Cardona that the word was being used all the time at her school, and she was upset because the students, one of whom was a friend, faced consequences that other students had not. He told her he understood, but that the word should not be said, and the issue had to be dealt with publicly because “it was interfering with education and learning.”

“I understand it now,” Pellegrino said. “He definitely had a way of addressing issues like that. You knew that you could trust him.”

Valentin, the Meriden teacher, says it’s a moment from about eight years ago that has stuck with him. A college student then, Valentin had just decided to pursue a teaching career. Cardona, who is Valentin’s mother’s cousin, had offered to let Valentin shadow him at Hanover. During his visit, two students got into a physical fight on the bus and were sent to the main office.

Valentin remembers watching Cardona calmly talk with the boys in Spanish, trying to get to the root of the problem. He sat down and heard them out, his voice sometimes growing stern but not harsh. Eventually, he de-escalated the situation, and the students were able to go to class.

It was an illustration of the school-level leadership skills that Cardona will take with him into a national role — skills that influenced many educators, like Valentin, continuing their own work in Meriden.

“The way he handled it was kind of like he was talking to members of his community,” Valentin recalled. It was like “someone who has experienced it before, versus someone who had read about it in a textbook.”