Melanie Hester could see her fifth graders were confused.

A history lesson she was teaching about Native Americans asked the students to think about how they could honor the cultural history of the land where the United States now stands. “Where are the Native Americans now?” her students wanted to know.

In the past, the Iowa City teacher would tell her class more about why Indian reservations were established, discuss the term genocide, and talk about what Native culture looks like today. This time, she held back. On her mind was a new Iowa law that restricts how schools can teach about topics like systemic racism and white privilege.

“That’s where I’m like, well, I’m not really sure how to answer that,” Hester said. “I kind of stuck to the lesson and if they didn’t understand, I just kept moving forward — which is not best practice.”

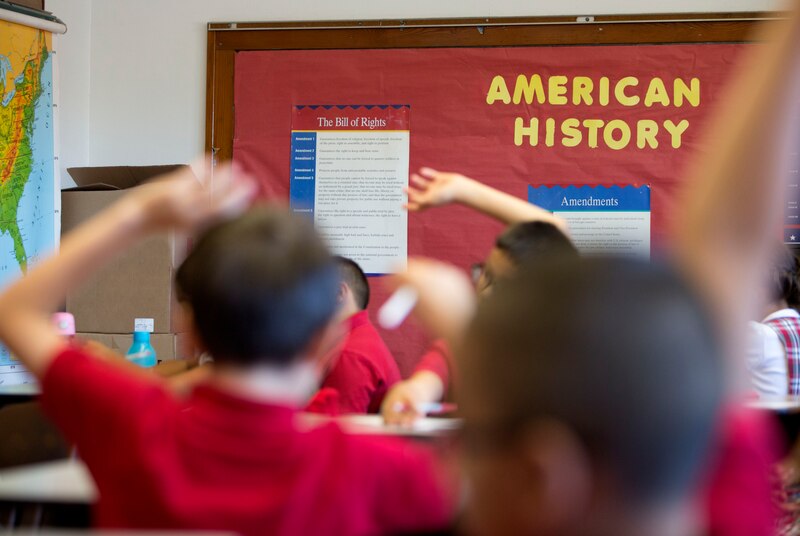

Across the country, new laws targeting critical race theory are influencing the small but pivotal decisions educators like Hester make every day: how to answer a student’s question, what articles to read as a class, how to prepare for a lesson.

Plenty of teachers say they haven’t changed their approach, and there is little evidence that these laws have led to wholesale curriculum overhauls. But in several states with new legislation, teachers say the ambiguity of the laws, plus new scrutiny from parents and administrators, are together chipping away at discussions of racism and inequality.

“A lot of that chilling won’t happen as overtly as cancelled courses,” said Luke Amphlett, a high school social studies teacher in San Antonio. “The real chilling effect is something that’s so much harder to measure because it’s those daily decisions made by educators in the classroom.”

Eight states now have laws restricting how schools can teach about racism and sexism, though they vary widely. All were passed in the wake of the protests for racial justice that defined 2020 — a year that also saw a range of institutions acknowledge the ways they have been shaped by racism.

Many school districts added anti-racism trainings, promised to review curriculum materials, or hosted class conversations about discrimination and justice.

Backlash arrived in the months that followed. Critics contend that many schools were overstating the importance of race and racism in lessons, distorting American history, requiring unproven or divisive training sessions, and making white students feel uncomfortable. “Critical race theory” became their catch-all term, and the new laws target the concept in different ways.

Iowa’s law says teachers can’t describe the U.S. or the state as “systemically racist or sexist,” though schools can teach about racist or sexist policies. In Texas, teachers who discuss a “widely debated and currently controversial issue” must do so “objectively and in a manner free from political bias.” And in Tennessee, the law bans 14 concepts, including the idea that individuals should feel “discomfort, guilt, or anguish” because of their race. The stakes are high: Tennessee teachers who cross the line could lose their teaching licenses, and school systems that look the other way risk losing some state funding.

Exactly how to avoid running afoul of the laws remains fuzzy to many educators, though, in part because they’ve been provided with little to no information from states about how the laws apply to specific teaching situations.

Tennessee officials have issued no written guidance about what is and isn’t allowed in class beyond the law’s list of banned concepts. Iowa officials did issue guidance, but it left educators with enough questions that the state’s largest teachers union has hosted several packed trainings to fill in the gaps.

In Texas, emails obtained by Chalkbeat show that the state is providing little in response to questions from educators, even as districts face local challenges to curriculum materials. (The Texas Education Agency did not respond to requests for comment.)

That uncertainty has left teachers and others who work in schools to freelance in a fraught climate.

Joanna Estrada, a library assistant in Donna, Texas faced a split-second decision recently while tutoring three elementary school students. They were reading a book about the women’s suffrage movement, and the two girls were perturbed to learn that women weren’t always allowed to vote. The boy in the group, who is Hispanic, remarked that he would have been allowed to vote. Estrada, though, pointed out that at one time the vote was only granted to white men. The students wanted to know more details.

“That’s where I was like — I didn’t want to go too much into it,” she said.

Then they turned to the next story, which was about placing Harriet Tubman on the $20 bill. The students wanted to know more about slavery and the Underground Railroad.

“I was hesitant to say something,” Estrada said. “I didn’t want to get in trouble.”

Talking about slavery is not prohibited by the Texas law, and its architects have insisted that the new laws would not limit such discussions. “I defy anyone to find one word of this bill that says we don’t teach the ugly parts of our history,” Texas Sen. Bryan Hughes said in August.

But the bill does ban the teaching that “slavery and racism are anything other than deviations from, betrayals of, or failures to live up to the authentic founding principles of the United States.” That, alongside the vague requirement for objectivity, has steered teachers away from frank discussions of the past in ways that lawmakers claimed would not happen.

“The bills’ vague and sweeping language means that they will be applied broadly and arbitrarily,” warned a recent report from PEN America, a free speech advocacy group, and could cast a “chilling effect over how educators and educational institutions discharge their primary obligations.”

Estrada’s experience is not isolated. In Des Moines, Iowa, Stacy Schmidt recently found herself trying to avoid the terms “systemic racism” or “systemic sexism” while teaching a lesson about the Gilded Age. When students asked why the financiers of the time period were all white men, Schmidt redirected a question back to them — “Let’s talk about that, why do you think?”

Other times, Schmidt has described a law’s discriminatory effect, or opted for terms like “structural inequality.” But there is something lost with those workarounds.

“If we don’t call the thing what it is, we lose the impact of being able to directly pinpoint — and then as a result, challenge — the structures that reinforce systemic racism and systemic sexism,” Schmidt said.

In some cases, the passage of these laws has encouraged parents to complain to school boards about conversations happening in their child’s classroom. School libraries are seeing a rise in book challenges this year, especially around texts written by authors of color or that deal with themes of race and identity.

This tense climate has left some teachers of color feeling especially vulnerable. That’s because they frequently get tapped to lead conversations about race and racism, and they often refer to their own lived experiences to help students make connections.

Hester, for example, fielded questions about her race from students in Iowa City whenever she wore her long hair down. Hester would turn that into a teachable moment by telling them about her background — she has Black and white parents and identifies as Black — and how the one-drop rule was used to classify enslaved people. Now, she worries that kind of discussion could make her a target for parent complaints.

“These natural conversations that normally occur in my class full of diverse students, they’re very surface-level now,” she said.

In some cases, the limits on teachers have put students of color on the spot.

In Iowa, Ames High School junior Theo Muhammad has a teacher who calls on him to explain concepts when discussion turns to racial inequity, or elaborate when she feels like she can’t go into more detail.

“I’ve talked about white privilege,” said Muhammad, who is a leader in the high school’s Students Advocating for Civil Rights in Education club. “She’ll not say it, and then I can say it.”

Students say that can feel like a burden, especially when the requests are directed at students of color.

“It puts so much more pressure on students to talk about it,” said Kenaiya James, an Ames High senior who is also a leader in the club. The hesitation she’s seen from her teachers this year has prompted her to change up her plans for the Black history month event she’s coordinating in February. She’s going to rely more on students, instead. “But then that also puts more pressure on students having to educate their teachers,” James said.

Still, a number of other educators have decided not to make any changes in response to the new laws. Skikila Smith, who teaches literature at a high school in Knoxville, Tennessee, says she can’t teach the story of racial injustice in “To Kill a Mockingbird” without addressing her students’ questions about George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and other Black Americans killed by police or vigilantes in recent years.

“If a student asks, I’m not going to shy away from answering,” said Smith, who is Black, like most of her students. “I’m not going to lie when they start making connections and asking why people don’t believe a Black person over the lies of someone who does not look like them. My students are not dumb.”

This summer, Smith wrote Gov. Bill Lee to ask how she’s supposed to comply without abdicating her responsibility to her students. Smith said she never heard back, nor has she received a list of prohibited topics from her district. (After publication, a spokesperson for the governor said his office listens to constituents and the state education department is in touch with schools and educators.)

For now, Smith has decided to teach her students the same way she did before the law was enacted.

“If this is civil disobedience, then come and get me,” she said. “I will not deny my students the truth.”