As the omicron variant of COVID spreads rapidly, schools are facing a fresh round of questions about how to respond.

This latest curveball comes at an awkward time, with some schools already closed for winter break or open for only a few days this week. And it remains to be seen exactly how substantial this wave will be, top health officials say, which will depend on whether omicron cases end up being less severe and whether more Americans get vaccinated and boosted.

What is clear is that some school systems are already adjusting course, but most have not yet made big changes to their plans for schooling in January or in-person learning this week. Here’s what we know so far.

Rising case numbers have caused disruption, but not widespread closures

The school tracker site Burbio estimated over 600 of the tens of thousands of American schools were unexpectedly closed at the start of this week. That’s an uptick from the prior weeks, but much lower than some weeks in November.

Local reporting in Maryland and New York suggests many of those schools saw dramatic spikes in cases among students and staff. Washington D.C.’s school district also announced Tuesday that it would extend winter break two days in January.

Even where the virus is surging, big school systems are staying open. In New York City, seven schools were closed and another 45 “under investigation” Monday, and some principals made it simpler for students to attend from home. The mayor has said wider closures of the system’s 1,600 schools are off the table, though those decisions will be made by a new mayor in January.

In Chicago, the schools chief said Tuesday that he expects schools to reopen as planned after the break, though individual classrooms could close. And in Philadelphia, district leaders said Tuesday they have no immediate plans for a shift to remote learning, though eight schools are temporarily closed.

The exception to that trend, for now: Prince George’s County Schools in Maryland, which drew headlines for its recent decision to switch to virtual learning until mid-January.

There are signs more are considering a switch, though. On Monday, the superintendent of Newark Public Schools warned parents and educators that the district was preparing for a “potential pivot to remote instruction” in January.

Some districts now lack the legal authority to entirely close on their own, like those in Tennessee, though individual schools there were granted permission to shutter for brief periods this fall in response to the delta variant.

There is widespread concern in the education community about the effects of additional school closures

Many educators and policymakers are warning against school building closures as a response, based on the academic, social, and economic effects of last school year’s widespread remote learning on students and families.

Students fell behind where they would normally be academically — especially low income, Black, and Hispanic students. This “learning loss” appeared to be worse when students received less in-person instruction.

Loss of in-person learning also means missed opportunities to connect with peers. One study found that students who learned virtually scored slightly worse on a survey of social and emotional well-being — like whether they felt that an adult at school cared about them and were generally feeling happy.

“We have seen the devastating impact of school closures and long-term virtual instruction on student learning here in Maryland and across the country,” Maryland schools chief Mohammed Choudhury said Monday. “When COVID-19 transmission increases and health measures become a necessity, schools must be the last places to close.”

Over the course of the pandemic, the research has been mixed on whether keeping schools open contributes to community spread of COVID, though conditions are continuously changing.

Unlike last year, children over 5 can now be vaccinated, although vaccination rates for younger children remain low.

Omicron appears more likely to infect vaccinated people than delta, which could make staffing shortages worse

Schools across the U.S. have struggled with shortages of bus drivers, cafeteria workers, and even teachers for months. Substitute teachers have been in particularly short supply, leaving schools with little wiggle room when educators are home sick or quarantining.

Prince George’s County, for instance, reported that hundreds of staff were either out sick with COVID or quarantining because of exposure to the virus.

Those staffing gaps contributed to a few districts’ decisions to briefly return to virtual learning over the last month. The challenges were widespread enough to prompt Education Secretary Miguel Cardona to ask states and districts to consider urgent new efforts to add staff, from signing bonuses to legal shifts that would allow retired educators to return to buildings.

The World Health Organization warned Monday that people who have been vaccinated or who have recovered from COVID are more likely to contract the new, fast-spreading variant than they were the delta variant. That could mean additional staff absences — even when vaccination rates are high — and more building closures where schools are already short-staffed.

The CDC is recommending schools utilize “test to stay,” which could keep more students and staff in school during a surge

In places like Colorado, the delta variant has posed a months-long threat to schools’ normal operation. There, school-based COVID outbreaks have been common, but schools switching to remote learning have been rare — largely due to relaxed quarantining rules.

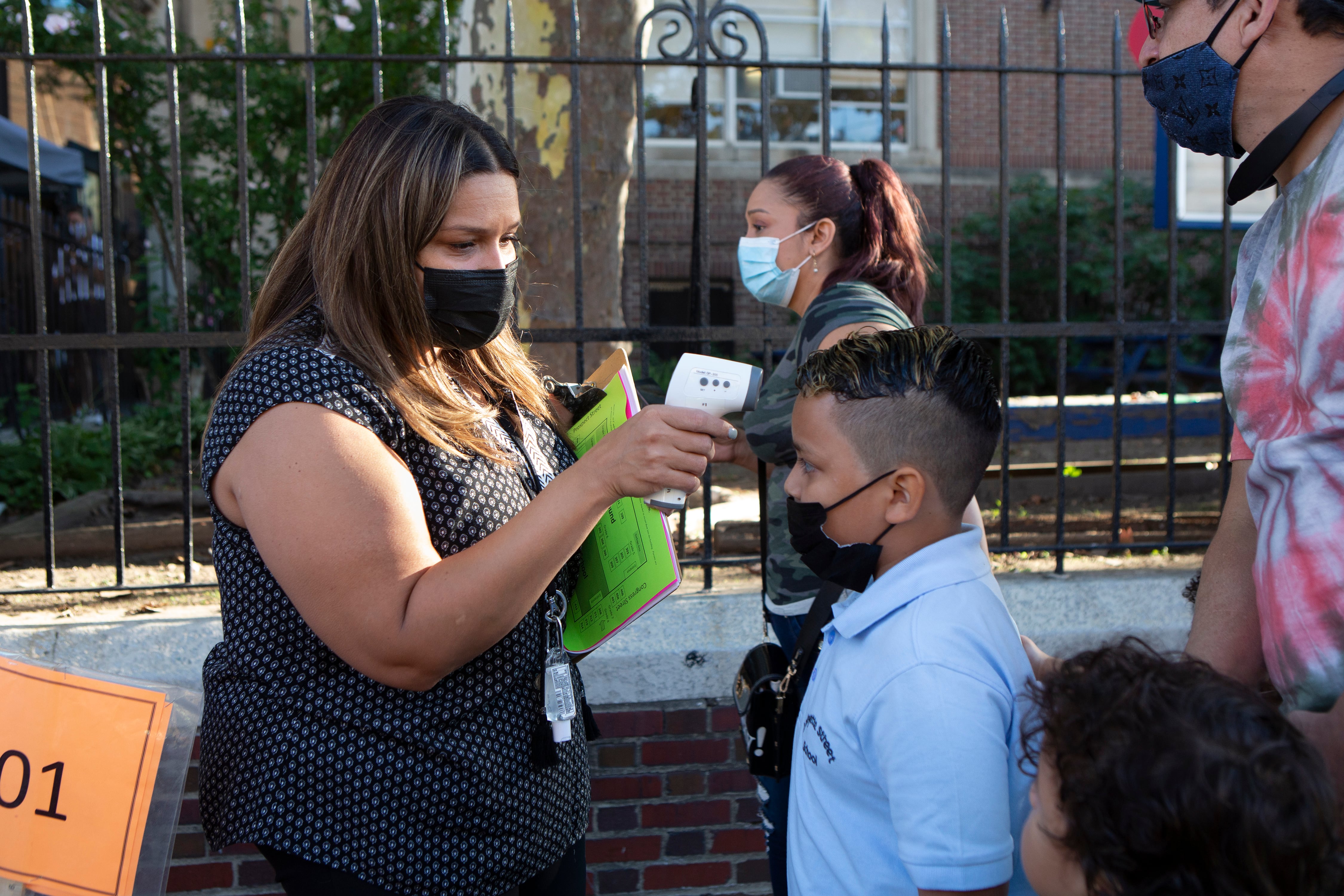

More schools are taking steps in that direction. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention last week endorsed “test to stay,” a protocol that allows unvaccinated students who would have had to quarantine after COVID exposure to instead remain in school if they have no symptoms and regularly test negative.

A variety of districts have adopted the practice, and state officials in New York and New Jersey signaled support on Monday. In places where most students haven’t given consent for frequent testing, the logistics of a true “test to stay” program remain difficult. Chicago is piloting it in just one school.

Districts are beginning to rely more on at-home testing, another tool to monitor and limit spread. Chicago is distributing 150,000 at-home tests meant for students before returning after winter break, and D.C. is asking families and staff to use the extended spring break to pick up tests of their own.

At-home rapid tests may be more accessible soon, too. President Biden announced Tuesday that Americans will be able to request free tests to be delivered to their homes starting in January.