Highly anticipated new guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says schools don’t need to wait for staff to be vaccinated to reopen. Students should return full-time where spread is low or moderate, and with regular testing, the CDC says schools can open for some in-person instruction even when community spread is high.

Masks and other safety measures remain critical, the CDC and the U.S. Department of Education said Friday. But it’s important to get schools open wherever possible to limit the effects of the pandemic on students whose educations have been disrupted, officials said.

“This pandemic has led to increased absences, fewer learning opportunities for students, more kids going hungry and more social isolation,” said Donna Harris-Aikens, an education department official. “For these reasons and more, we need to get kids back in the classroom.”

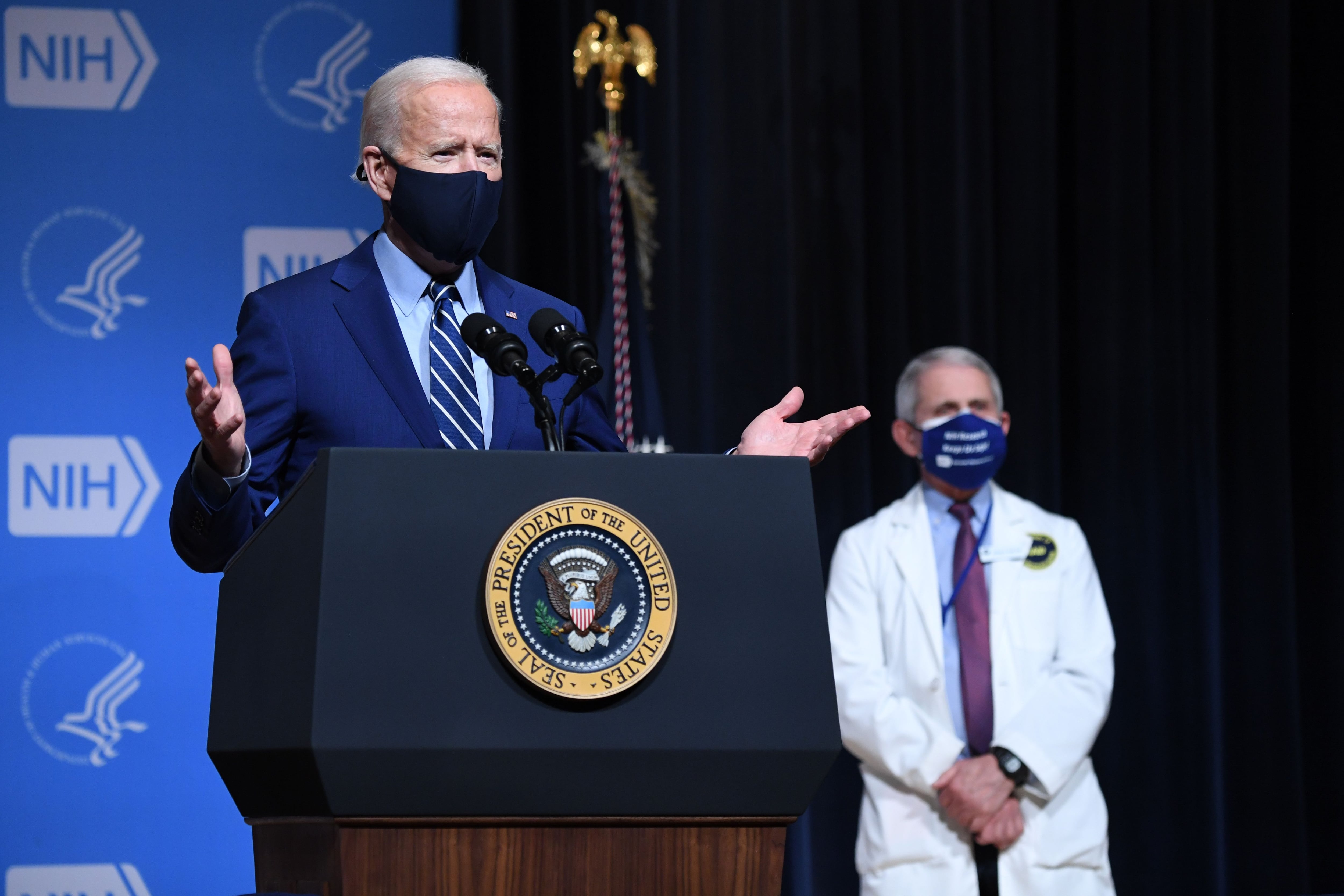

The guidance offers a high-profile boost to those pushing schools to quickly reopen or stay open, including some governors, school officials, and frustrated parents. Recent estimates suggest that about a third of U.S. students lack access to at least some in-person schooling, and the Biden administration has staked its goal of reopening more schools in part on new, robust guidelines.

Still, the CDC says schools should consider hybrid schedules or stay virtual if spread is high and widespread testing isn’t possible. Under the CDC’s definition, about 90% of the country qualifies as an area with high community spread, and testing programs are expensive, which means it may be logistically challenging for districts to fully open their middle and high schools and comply with CDC guidance.

Ultimately, state and local officials will decide how much weight to give the CDC’s recommendations. Many districts already have plans to bring more students back over the next month or two; in other places where school officials and educators share safety concerns and parent demand for in-person school is lower, the guidance may hold little sway.

Another piece of uncertainty: the more-contagious variants of COVID that have shuttered schools in many countries and are now circulating in the U.S. If those variants cause cases to spike, the CDC warns, “updates to this guidance may be necessary.”

What the guidance says

In places where schools have not reopened, some teachers unions have pushed to wait until staff are fully vaccinated. The CDC says that’s not necessary, but encourages states to prioritize vaccine access for teachers.

“Teachers and school staff hold jobs critical to the continued functioning of society and are at potential occupational risk of exposure,” the CDC guidance says, and officials should consider giving “high priority” to those staffers once health care workers and others in the most-vulnerable category have been vaccinated.

The guidance does offer a framework for deciding how and whether to open school buildings. In places with low or moderate community spread, the CDC recommends elementary, middle, and high schools be open full-time. In places with “substantial” spread, schools should open to students part-time.

In places where community transmission is highest, schools that regularly test students and staff should open part-time. If that kind of surveillance testing is not in place, elementary school buildings can remain open part-time, but middle and high schools should remain virtual.

(The CDC defines low community spread as 0-9 new cases per 100,000 people over seven days; moderate as 10-49 cases, substantial as 50-99 cases, and high as more than 100 cases. Low spread also corresponds to a seven-day test positivity rate of under 5%, while moderate is under 8%, substantial is under 10%, and high spread is over 10%.)

“The safest way to reopen schools is to ensure that there is as little disease as possible in the community,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky said.

Those are very conservative thresholds, noted Susan Hassig, an epidemiologist at Tulane University — too conservative, in her view. “I started hopping all over the map ... I couldn’t find any place that was under 100 [cases per 100,000], except in the middle of nowhere,” she said. “I didn’t see a good justification for those categories.”

Across the country, many schools are already open with a hybrid schedule. Students come to school only a few times a week in alternate groups in part to maintain physical distances of at least six feet and minimize crowding in common spaces.

The new guidance continues to broadly recommend those six-foot distances, which may encourage schools to stick with those part-time schedules. But the CDC also says that in areas where community spread is low or moderate, less than six feet of distance is OK. The six-foot standard is only required in areas with substantial or high community spread.

“We’re worried that people will not be able to get back to full in-person learning if we mandate six feet,” Walensky said. “We believe that at such low levels of transmission, schools could be kept safe simply with universal masking and all the other three mitigation strategies.”

Health experts raised concerns about some of the CDC’s choices Friday. Hassig thinks the CDC should have been more consistent about social distancing requirements regardless of community spread.

On the other hand, Rebecca Haffajee, a health policy researcher at RAND, says she would have liked to see a little more leeway on distancing based on students’ age. “Evidence suggests this is very likely age-dependent — with younger kids being relatively safe with closer to 3 feet,” she said.

Haffajee, and a number of other experts, were also puzzled that the CDC didn’t put more emphasis on ventilation, which can limit the airborne transmission of COVID-19.

Still, both Haffajee and Hassig said the new guidance provides valuable information to school officials. “It’s a relief that we finally have some more robust federal guidance to help achieve consistency in school approaches,” said Haffajee.

The CDC acknowledged that some schools that are currently open, though, are not following all of its safety recommendations.

“For these schools, we are not mandating that they close,” Walensky said. “Rather, we are providing these recommendations and highlighting the science behind them to help schools create an environment that is safe.”

Will the new guidance change schools’ plans?

The guidance comes amid a pitched national debate over school reopening, and puts the Biden administration in tension with some teachers unions, key political allies. In California, most public school buildings are closed, and the unions in a number of large districts don’t want them to open until teachers are vaccinated.

Still, national union leaders praised the guidance, suggesting they plan to use it to push for stricter safety measures.

Becky Pringle, president of the National Education Association, called the guidance a “good first step,” but argued that schools often lack the resources to follow the CDC’s guidelines. “Many schools, especially those attended by Black, brown, indigenous, and poor white students, have severely outdated ventilation systems and no testing or tracing programs,” she said in a statement. “State and local leaders cannot pick and choose which guidelines to follow and which students get resources to keep them safe.”

“Today, the CDC met fear of the pandemic with facts and evidence,” American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten said in a statement. “For the first time since the start of this pandemic, we have a rigorous road map, based on science, that our members can use to fight for a safe reopening.”

Complicating matters further: Many parents are also reluctant to send their children back to school buildings. In some places that have reopened schools, only a small share of students have returned. Families of color are particularly wary of returning, and schools serving students of color have been less likely to offer in-person instruction.

Reopening has also become highly political, with Democratic areas much less likely to open buildings. And while many school officials have long hoped for clearer guidance from the federal government, particularly in the wake of reports that the CDC had been politicized under the Trump administration, the new information comes long after officials have to come to rely on other sources.

“Lack of national leadership trickles down and creates problems,” one superintendent explained on a national survey.

What could increase the influence of the guidance: Virus cases are declining across the country, and more schools are already opening or have plans to do so. The fact that the new guidance comes from the Biden administration may bolster its credibility with some school officials.

“Superintendents can’t necessarily pay attention when the CDC is weaponized and politicized,” said Noelle Ellerson Ng of AASA, the national school superintendents association. “This new guidance is the type of leadership that our school leaders have needed.”

At the core of the CDC’s guidance is the point that COVID spread in schools is low, but the harm caused by keeping buildings closed is high.

Parents whose children are learning in person five days a week are more satisfied with their education. The share of high school students failing courses has jumped substantially. Standardized tests show students falling behind. A recent study in Ohio found that the share of third graders who scored proficient on a reading exam dropped from 45% last year to 37% this year.

Meanwhile, contact tracing efforts across the country have found that COVID can spread in schools, but transmission is fairly limited.

For instance, one much-publicized CDC study of 17 rural Wisconsin schools found that only a handful of students and no teachers were known to have contracted the virus in school. Another national study found that reopening school buildings didn’t increase the community’s COVID hospitalization rates, at least when community spread was low to moderate.

Another Wisconsin study released by the CDC shows a substantial share of cases from COVID outbreaks last fall were linked to day care facilities and K-12 schools.

One key aspect of Biden’s reopening push — a massive infusion of additional money for education — was mentioned Friday, but still requires Congress to act. That funding may be particularly relevant to whether more schools are able to offer the kind of widespread testing that the CDC suggests could help schools open even when community spread is high.

“Science tells us that if we support our children, educators, and communities with the resources they need, we can get kids back to school safely in more parts of the country sooner,” President Biden said in a statement.