Schools across the U.S. will receive a massive and historic infusion of money in the coming months thanks to a pandemic relief package that includes $128 billion for K-12 education and hundreds of billions for state governments.

Congress approved the package, known as the American Rescue Plan, on Wednesday. White House press secretary Jen Psaki said that President Biden, who proposed and championed the legislation, will sign it into law Friday.

The result is a dramatic reversal in fortune for school budgets. When the pandemic shuttered schools and businesses last spring, experts warned that the ensuing economic dip threatened to hit the country’s disadvantaged schools hardest. Now, some of those districts may find themselves flush with cash.

The new money comes to nearly $2,500 per student nationwide, but high-poverty districts will see more. Cleveland’s school district, where the vast majority of students come from low-income families, will receive roughly $8,000 per student, on top of the $4,500 per student it has already received in pandemic relief. Tulsa Public Schools in Oklahoma is expecting to receive $3,700 per student, on top of the $2,300 per child it has already received.

“The federal government has stepped up in a big way,” Derek Richey, Cleveland schools’ chief financial officer, said last week.

“This package is especially large, more than twice that of previous efforts,” said Bruce Baker, a Rutgers University school funding researcher.

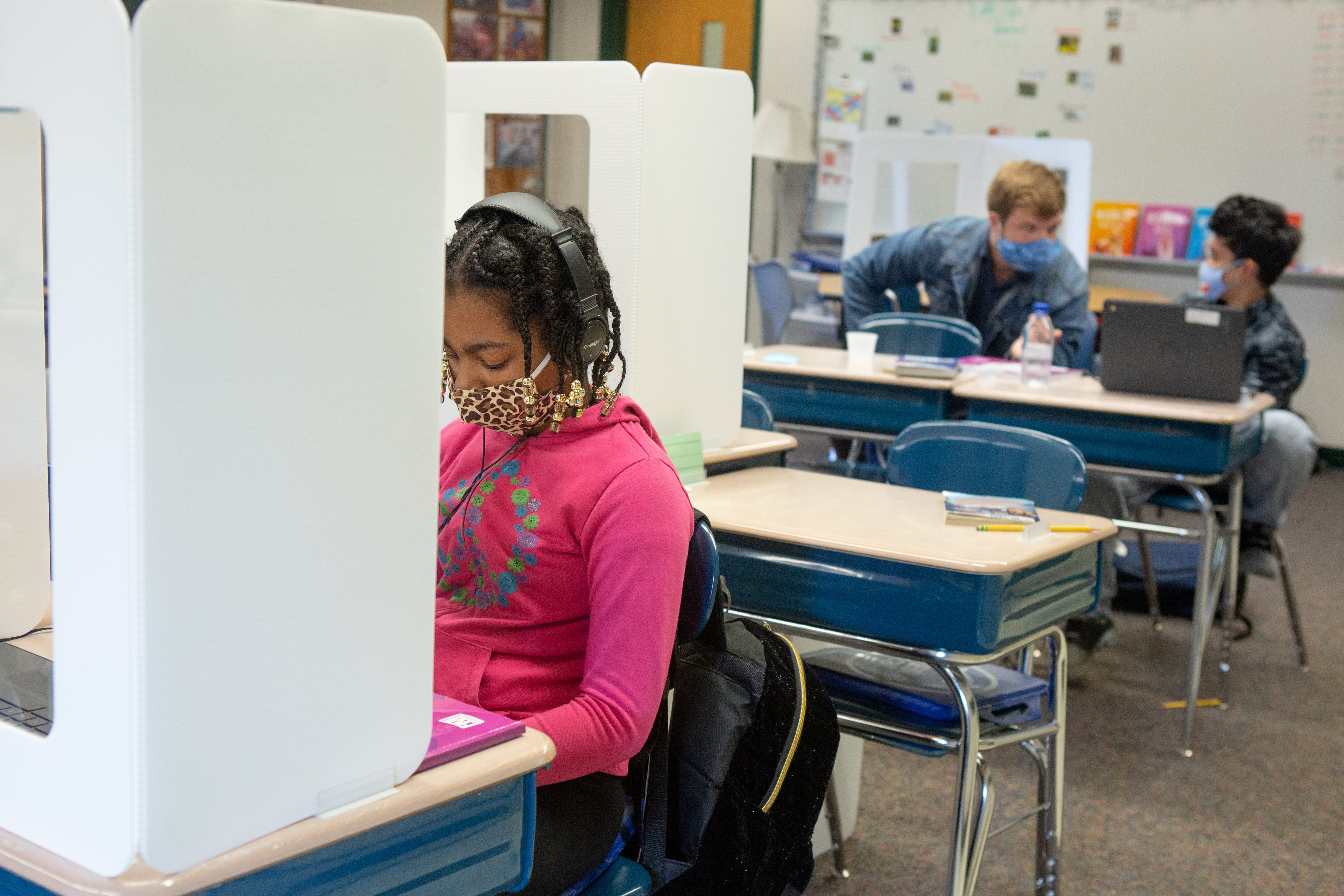

President Biden has suggested the new money will help more schools open their doors for in-person learning. But the money is unlikely to eliminate some of the challenges that have kept schools from fully reopening, including fear among families and educators and inadequate space to comply with the CDC’s social distancing recommendations.

What the money will do is give schools the resources to set up the kind of costly, large-scale initiatives — like offering small-group tutoring or extending the school day or year — that research indicates could help students catch up after months of disrupted learning.

The funds, then, offer an opportunity and a test for America’s schools. Can they use this new money, quickly, in ways that help students who need it most? The answer could determine whether the pandemic does long-term academic harm to a generation of children.

What’s in the deal: money for schools, states, and families

The package is likely the biggest single federal outlay on K-12 education in U.S. history.

It includes nearly $110 billion that will flow to school districts through the Title I formula, which is based in large part on how many low-income students a district serves. That means some of the country’s highest-poverty districts will end up with thousands of additional dollars per student, while many affluent areas will wind up with less than $1,000 more per student.

Districts must use at least 20% of their money to address learning loss. Other than that, schools will have broad latitude to use the money for anything from buying masks to keeping teachers employed to setting up an after-school program.

States will also get billions to help schools address learning loss and create after-school and summer school programs. Another $800 million must be used by the U.S. Department of Education to identify and support students who are homeless. Separately, nearly $3 billion is earmarked to support students with disabilities.

Another $2.75 billion will go to governors to distribute to private schools that serve a “significant” share of low-income students.

In another boon to public schools, states and cities will get $350 billion to fill their own budget gaps. Education advocates see this as critical, since states provide a substantial share of schools’ funding.

All this money, in addition to the relief packages passed last year, means that most schools are unlikely to face imminent budget cuts, which were a distinct possibility when the pandemic hit and the economy cratered.

“That’s really a testament to the power of federal support,” said Zahava Stadler, who works on school funding issues for Education Trust, which advocates for federal aid. “We really need to be thankful for the breathing room that this federal aid has provided.”

Schools’ overall financial pictures will vary, based in part on how they have weathered the pandemic so far. One recent analysis found that many districts that have offered in-person instruction have been running a budget deficit, while several all-remote districts have saved money.

The deal includes a number of other provisions that will affect schools.

A $7 billion Emergency Connectivity Fund will provide funding for schools to pay for internet and devices for students learning from home.

Another provision will temporarily expand the child tax credit, which will provide at least $3,000 per child to low- and middle-income families. Overall, the package is projected to reduce the country’s child poverty rate from 13.7% to 6.5%, with particularly large declines for Black and Hispanic children.

One thing not in the deal: a “challenge” grant program proposed by Biden several months ago. The idea, which would have had states and districts complete for additional funds, was nixed after some education advocacy groups lobbied against it, fearing a repeat of the controversial Race to the Top program included in the 2009 stimulus package.

The goal of the money: address learning loss and get school buildings open

Will this help more schools open their doors?

One in four students in U.S. public schools do not have access to in-person instruction, according to a recent estimate, and it’s not clear that money has played a decisive role in whether schools have opened or not. Congressional Republicans, who voted against the deal en masse, have criticized the deal for funnelling money to schools that haven’t offered in-person instruction despite earlier rounds of pandemic relief.

“Only 5% of the K-12 education funding will be spent this year, even as Americans are told this money is needed to reopen their children’s schools,” said Rep. Jason Smith of Missouri, referring to a Congressional Budget Office estimate of how quickly schools will use the new money.

Baker, the Rutgers researcher, points out that that money won’t quickly solve space constraints or teachers’ and students’ reluctance to return to buildings. “If people are not comfortable walking into a class of 30 to 35 sneezing 9 year olds, I don’t know how we resolve that with this money in a month,” he said.

Still, the funds will help cover districts’ pandemic-related safety costs, particularly ones that run into next school year.

“The jury is still out on what that ‘new normal’ of operating costs is going to be,” said Jorge Robles, chief operating officer of the Tulsa Public Schools. “If we’re talking about another year of supplying masks and PPE as we get everyone vaccinated … that’s a whole different level of baseline expenses.”

The other major use for the new dollars will be attempting to help students make up lost learning and address the social and emotional toll of the pandemic. Studies from fall 2020 show that students have fallen behind where they would have been if not for the pandemic. Course failure rates have also spiked.

Some places, like Tulsa, have already gotten started. Last week, the district announced a battery of new programs that will span the next 18 months: summer day camps at all schools, expanded before- and after-school programming, tutoring for students who have fallen behind, and extra counseling for high school juniors and seniors.

“All those funds will go towards this, so that we can actually support our kids,” said Robles. “We know that it will take more than one year to do that.”

Will districts like Tulsa succeed? There’s reason for optimism. Research shows that when schools get more money, students tend to do better on tests and are more likely to graduate.

At the same time, rapidly spending a massive sum of one-time cash comes with serious challenges. “How they would ever spend that money effectively, knowing or at least expecting that all of it’s going away in a few years, concerns me,” Baker said.

Districts will have until October 2024 to allocate the funds, a U.S. Department of Education spokesperson said.

If schools use the money for recurring costs — like hiring more teachers or paying existing teachers more — that could lead to a “funding cliff” requiring painful cuts when the money runs out. Experts suggest that schools should instead consider expenses like building repairs, short-term tutoring, or extended school day programs that use existing staff. During the last recession, schools had to make substantial cuts after federal funds dried up.

“That cliff was deep,” said Richey, the Cleveland CFO. “We will have to learn from that experience.”

Correction: An earlier version of this piece said schools must spend the stimulus money by October 2023. In fact, districts will have an extra year beyond the timeline described in the legislation to allocate those funds.