Before school, my new Apple TV setup blasts the blues (obviously). An expensive air filter purrs. Cords snake around my feet. I’m lodged behind a cockpit of keyboards and monitors, staring at the webcam, ready to talk and listen and share and move windows and open and close breakout rooms and type encouragement into a chat box.

I’m lucky. My Bay Area district spent money so my classroom would be safe and conducive to learning when hybrid instruction began in mid-March.

Yet, every period, fewer students join me in that room. I put on a KN95 and fling open the door and a kid or two leans against lockers in the hallway.

The return started off differently. I had nine, 15, and seven students initially signed up for my one ninth grade and two senior sections, or 31 out of 70 students. Despite being a reopening skeptic, I was ecstatic to see them.

Now they’re leaving again, heading back to Zoom, this time by choice. The tedious (but necessary) safety protocols detailed on-campus tours spurred a few defections. But the major exodus began after hybrid started. By the second Friday, I was down to seven, three, and three.

It’s not because they hate me. I know because I’ve asked (jokingly). My colleagues have seen the same attrition.

In some cases, students have become full-time providers and caretakers, and returning to school has proved too tough on their families. Students run ad hoc daycare centers. Some work long hours at Target or KFC. Given their greater autonomy, more seniors have left. Latinx students, 65% of our school population, have returned home in greater numbers, too.

But there are other forces driving them away that we have to understand and confront at the institutional level.

School itself has never been fun or fulfilling for a lot of kids. The joy comes from playing sports, doing plays, going to rallies, seeing friends, and soaking up the hallway energy. Now, all of that is gone. School, which always was controlling, is now licensed to control them even more.

Back in the building, they have to follow arrows in tape and get told to wash their hands every 10 seconds. They’ve lost the ability to turn off their cameras when being seen becomes overwhelming. And with every departure, students who remain feel more out of place in the place they’re supposed to be.

One student, explaining her decision to leave, said she felt guilty. I begged her not to worry, but also begged her classmate, one of three remaining in seventh period, not to abandon me. I wasn’t completely joking this time. It feels like a logical eventuality that one morning I will fling open the door and no one will be waiting.

It also feels like it doesn’t have to be this way. A high school could become a more hospitable place in this (hopefully brief) liminal phase of hybrid learning.

I’ve written elsewhere about reimagining my curriculum. Why not reject conventional parameters in every respect? Why couldn’t grade-level cohorts participate in masked “field day” games? What about an outdoor concert on the football field? Or advisory sections meeting for local hikes? A battle of the bands. A talent show. Make such events features of the transition, in the last third of a school year everyone understands to be highly unusual.

My school went entirely remote for three days in April to make the first of three rounds of standardized testing go smoothly. We’re doing it again for a week in early May. No administrator wants this, and everyone understands the irony of the predicament. But if this is cause to rearrange the schedule, why not do so every Friday for an event designed purely to entertain and welcome students?

Combating learning loss will involve summer school, after-school tutoring, more aides, and smaller classes. A big part of the solution needs to be non-academic, though, because what makes students feel more comfortable at school makes them more invested in their education. A dramatic improvement of mental health support resources is a given. If school makes them feel alienated or unseen, we must address that too.

For three years, I taught at a charter school that ran like a kooky dictatorship. I was very happy to leave, but the founder and staff understood something important: school doesn’t have to always feel like school. Kids there actually enjoyed their field day tradition, when they were separated into groups across grade levels to pick team names, design T-shirts, write chants, and compete. It was corny and fun.

Even at its best, remote instruction was (and is) sad, but the pallid reality of the return hurts too. We are not doing enough to meet the moment, one when students need to feel a sense of belonging and opportunities for joy and healing, not a flimsy, germaphobic simulation of a tired routine.

These have been the most frustrating nine months of my career. I’ve seen my profession excoriated for laziness and callousness. Very loud and influential voices called for school campuses to reopen so students could be happier, healthier, and smarter. But few have called for students to show up with such urgency, and even fewer have shared ideas about getting them to stay. After a year that might have taught us a lot, it feels like we haven’t learned enough.

This is a lesson for the post-pandemic school years ahead, as well as for the rest of this one. After asking kids to do school at home, we need to teach them to feel at home at school. We need to be innovative and playful as well as rigorous.

The pandemic smashed old structures. Now we can draw up new plans.

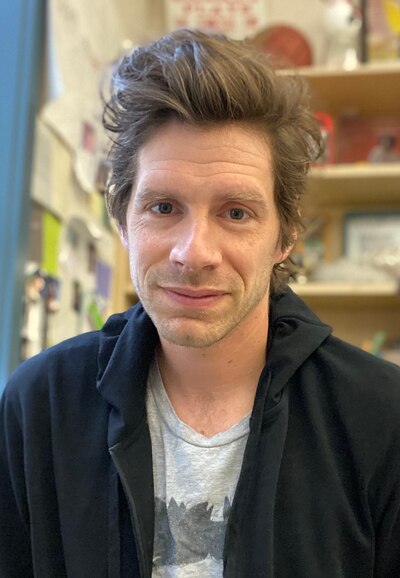

Andrew Simmons teaches high school English in the Bay Area. He’s written for The Atlantic, San Francisco Chronicle, Edutopia, and other publications. His 2020 book for educators, “Love Hurts, Lit Helps” (Rowman & Littlefield), addresses how English class literature can help improve teens’ friendships and relationships.