Summer school is getting an overhaul in Washington, D.C. this year.

Schools are designing programs to help students learn key concepts they missed during the pandemic, while also getting them ready for what’s coming next school year. Fourth and fifth graders may design roller coasters, while second and third graders could dive into the debate over who deserves a public monument.

The goal is to get students excited about school, and to help students who need it most without making them feel like they’ve fallen completely off track. And those programs have a new name: “acceleration academies.”

“We want to stay forward-looking and recognize that we don’t want to just reteach all of last year’s content,” said Corie Colgan, who heads the school district’s office of teaching and learning. Acceleration, she said, “shifts you to think about OK, how can we speed up this process?”

It’s a term popping up across the country as school districts look to fill in learning gaps after more than a year of interrupted learning.

That shared dilemma has some educators worried about the impulse to reteach concepts students might have missed during the pandemic, passing over or delaying new content. By doing so, schools risk spending so much time trying to fill in gaps that they create new ones — an outcome some fear could deepen existing inequities in education.

A push to “accelerate” has become a common response to that fear.

There’s healthy debate about how much the new efforts will truly depart from the ways schools have addressed learning gaps in the past, or is more about using language that shifts how teachers and students feel about the catch-up work. But the national focus on acceleration is picking up steam as school districts plan summer school and how they’ll approach next school year — meaning it could have a tangible effect on how students learn in the months and years to come.

“Nobody wants to be seen talking about failing kids or retention,” said Isobel Stevenson, a former school administrator whose organization, the Connecticut Center for School Change, is offering schools training on how to accelerate lessons. “You’ve got to have some kind of counter to some of the very negative ideas out there.”

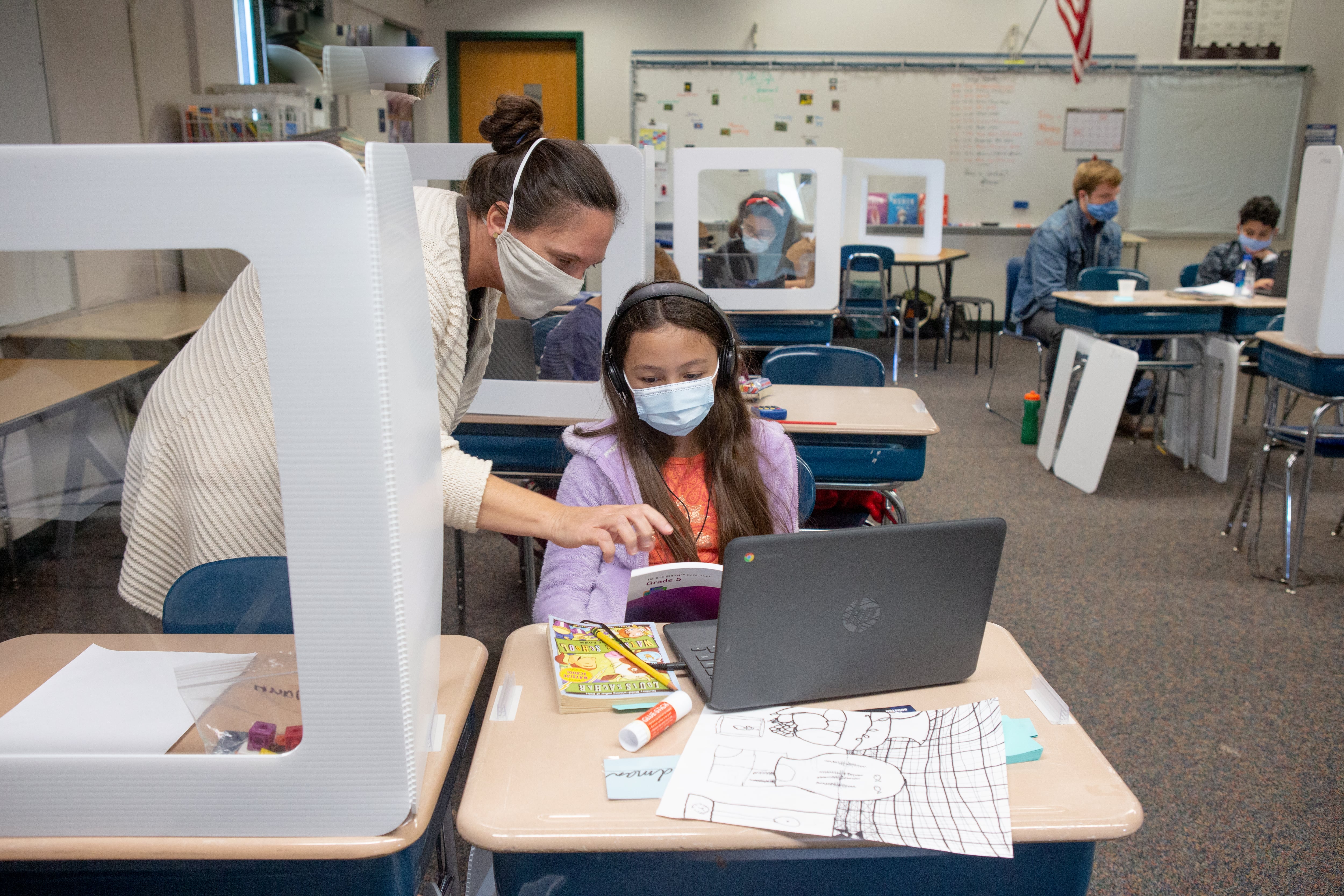

Generally, acceleration means focusing on teaching students lessons appropriate for their grade level, and reteaching only the skills and lessons from earlier grades that are necessary to understand the new content. That can happen in class, or before or after school.

The federal education department recently recommended the strategy, and several states have already identified a smaller set of key learning standards for each grade to help teachers choose where to focus.

And while the concept of acceleration existed before the pandemic, new money from the federal stimulus packages means schools will be able to hire additional staff, offer students additional learning time, or buy better learning materials — all of which can help make acceleration happen.

In Michigan City, Indiana, schools have already begun putting students in small acceleration groups. At Edgewood Elementary, for example, teacher Patrice Huley spends her school day focused on fourth-grade concepts with her whole class. After school, she is paid extra to work with eight of her students on reading and math skills from prior grades that connect to their fourth-grade work.

In their acceleration groups, Huley’s students might practice the third-grade skill of multiplying single-digit numbers by counting columns and rows, setting them up to work on multiplying double-digit numbers in class. Huley also introduces her acceleration students to upcoming vocabulary — recently, “ferocious” and “fripperies” from a fourth-grade American Revolution unit — so they’ll be familiar with the words when they encounter them in class.

“They’re doing better, and not only after school,” she said of her students. “Those skills are translating to the classroom.”

Educators say an important part of acceleration is to make sure students don’t feel that they’ve fallen far behind, which could ultimately hurt students’ confidence or lead them to become disengaged.

Huley works on that in her class. “You’ve got this” and “I want to know what you’re thinking” are phrases she says often. And Edgewood principal Kristin Smith says how the school presented the extra help mattered, too.

“Just the simple change in phrase of ‘acceleration’ — the students felt chosen,” Smith said. (It helped, Smith added, that students were eager to spend more time with their teachers and classmates after being away from school buildings for so long.)

While some see acceleration as the counterpoint to “remediation” — which is essentially reteaching content from prior grades — others say that’s not always a helpful distinction. Some see it more as a continuum, and schools just need to strike the right balance between old and new content to keep students moving forward.

“It’s mostly semantics — but it’s semantics that has a big mindset shift attached to it,” as Colgan, of D.C. Public Schools, put it.

A key proponent of acceleration has been TNTP, a national nonprofit that released a guide to acceleration that’s become a go-to resource for some school districts.

“In the past, I think we’ve prioritized everything from the prior grade, and said everything matters,” said Jamila Newman, who co-authored the guide.

Their goal is to get schools to move away from spending too much time on reteaching, especially topics disconnected from what students should be learning in their grade. Newman and others at TNTP say this was not an uncommon experience for students before the pandemic, especially if they were from a low-income family or students of color.

They point to a 2018 TNTP report — based on observations, surveys, and reviews of classwork in four school districts and a charter network — that found students spent only a quarter of their school year on “grade-appropriate” assignments. (It’s worth nothing the findings are based on the organization’s subjective ratings method.)

What’s less clear is whether teachers and schools are being set up to do acceleration well. Federal officials and educators who support this strategy say it requires a lot of planning and teamwork among teachers and administrators, who will likely have to map out new schedules and figure out how to group students for extra help.

“This also involves a rethinking, in many cases, of how you put the whole school personnel to work,” said David Steiner, a professor of education at Johns Hopkins University who has been supportive of acceleration. “I don’t want to in any way suggest this is easy.”

It could be even harder if schools don’t provide the training educators need, or if schools lack a cohesive curriculum that makes clear what students are expected to learn, and when. And like all pandemic recovery efforts, there’s a risk it could be written off if clear evidence of success doesn’t emerge quickly.

Some see this as a long-term strategy. Colgan says her district is trying to keep expectations realistic about how much can be tackled during their summer acceleration academies, some of which last just two or three weeks.

“We’re not necessarily going to see dramatic changes immediately in all of the academic data,” she said of this summer, “but if they choose concrete skills that they know the students need to learn, that are critical for the upcoming grade level, they can see some progress.”

And that’s not where acceleration ends — Saturday school, vacation academies, and other kinds of support are planned for next school year.

“We asked them to take a long view,” Colgan said.