For the last few years, the Dallas Independent School District has been trying to make some of its schools more economically diverse — and hearing from other districts curious about doing the same.

Its integration program reserves half of a school’s seats for students from low-income families, and the other half for middle- and higher-income students. And while just 14 of the district’s 230 schools are participating this fall, the ambitions are big in a highly segregated district: to create schools that are attractive both to families who already send their children to local public schools and those who might have otherwise bypassed them.

“There’s an appetite for more because we’ve got wait lists of families,” said Angie Gaylord, the Dallas school official overseeing the effort. “It’s been interesting to see so many districts coming to us to see the work.”

Now, President Biden wants to give more school districts money for similar initiatives. His federal budget proposal includes a $100 million grant program that would allow schools to apply for funds to make their schools more racially or economically diverse.

That’s a tiny slice of federal education dollars. But the program could represent a notable shift in federal education policy from indifference or even hostility to school integration to active support of it. If the proposal becomes reality, the Biden White House will arguably have done more to further school integration than either the Trump or the Obama administrations.

“Money helps to both pilot, start, and scale, and so let’s not sleep on that,” said Mohammed Choudhury, who worked on integration efforts in San Antonio and Dallas and will become the Maryland state schools superintendent next month.

At the same time, there is no indication that Biden or Education Secretary Miguel Cardona will make desegregating American schools a central priority — and there are plenty of powerful forces pushing in the opposite direction.

The pandemic strained school communities, and local officials may be particularly wary of any changes perceived as disruptive as they face steep enrollment declines. Legislatures currently banning the teaching of “critical race theory” in classrooms are unlikely to look kindly upon attempts to integrate schools that explicitly consider race. The federal judiciary has grown increasingly skeptical of those efforts, too.

When asked about his plans in a recent interview, Cardona pivoted to talk about factors outside of education policy that drive school segregation.

“We have to be part of the solution. And there are options within the schoolhouse or school systems to provide diversity,” he said. “But I also think we have to look at it more holistically and make sure we’re part of the conversation around how the environment where schools are located lack diversity, or lack the ability for people to move if they so choose to.”

America’s schools are highly segregated by race and family income. In 2018, 40% of Black students in the U.S. attended a public school where 90% or more of their peers were students of color. In 2019, the typical low-income student went to a school where two-thirds of their peers were also low-income, according to an analysis provided to Chalkbeat by University of Southern California researcher Ann Owens.

The halting — and even reversal — of progress toward racially integrating American schools came as courts eased up pressure on desegregation and limited schools’ ability to design their own integration programs.

In the 2007 case Parents Involved v. Seattle, the Supreme Court struck down district-created integration plans that considered students’ race in school assignments, ruling that such programs were discriminatory. “Before Brown, schoolchildren were told where they could and could not go to school based on the color of their skin,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts. “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.”

Those legal and political challenges help explain the focus on programs like the integration grants, which advocates, lawmakers, and education department officials have been trying to get off the ground for years. Then-Secretary of Education John King launched a smaller $12 million grant program at the end of the Obama administration that Trump officials canceled a few months later. An expanded grant proposal, the Strength in Diversity Act, passed the House but stalled in the Senate last year, and hasn’t gone anywhere yet this term.

As the Biden administration put together its budget plan, it incorporated aspects of that bill. We “had been thinking about proposals that had bipartisan support, that were voluntary, that were state- and/or district-led and driven,” said Jessica Cardichon, deputy secretary at the Department of Education. “What is the appropriate federal role? Providing the resources to help support those efforts.”

Democrats, who narrowly control both houses of Congress, are optimistic the Biden program will survive the budget process, which wouldn’t require Republican support.

“We recognize there are serious consequences often associated with racial isolation in schools,” said acting assistant secretary for civil rights Suzanne Goldberg. “Schools with a significant or majority or entire populations of students who are Black and Brown tend to be lower-resourced schools.”

Crucially, that program could fund planning efforts — which are often complicated and politically difficult — and create more examples of successful integration strategies.

“Pushing integration high enough on the list can be a challenge, and when there are no resources to support that, it’s especially difficult,” said Halley Potter, a senior fellow at The Century Foundation, a progressive think tank that supports school integration work.

Some see this as a promising moment. As the pandemic recedes, school districts will have more time and space to consider changes. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder last year, many districts expressed a renewed interest in improving conditions for students of color, who have been found to benefit from integrated schools. Advocates say that momentum could still be harnessed, though it’s unclear whether backlash to racial equity efforts will impede that work.

“It’s hard to tell what direction this is headed in,” said Stefan Lallinger, who heads the Bridges Collaborative, a group of school districts, housing authorities, and other organizations working to advance school integration. “Do you think of the segregation that exists in your community as part and parcel of the broader racial injustice that exists ... or are you able to, in your mind, separate the fact that your child goes to a segregated school from that fact that you participated in a Black Lives Matter protest a month ago?”

In the last year, lawmakers in North Carolina and Massachusetts have proposed legislation to further school integration, and districts like Milwaukee have revived talks, too, noted Gina Chirichigno, the director of the The National Coalition on School Diversity.

“There has been a shift,” she said. “People are really thinking about the longer-term issues and seeing this as an opportunity to change some things.”

But the voluntary grant program would not prompt any changes in the many segregated communities where officials have no interest in volunteering. It will also likely be a hard sell to get districts to collaborate on integration — something critical to real progress, since most segregation occurs between schools in different districts.

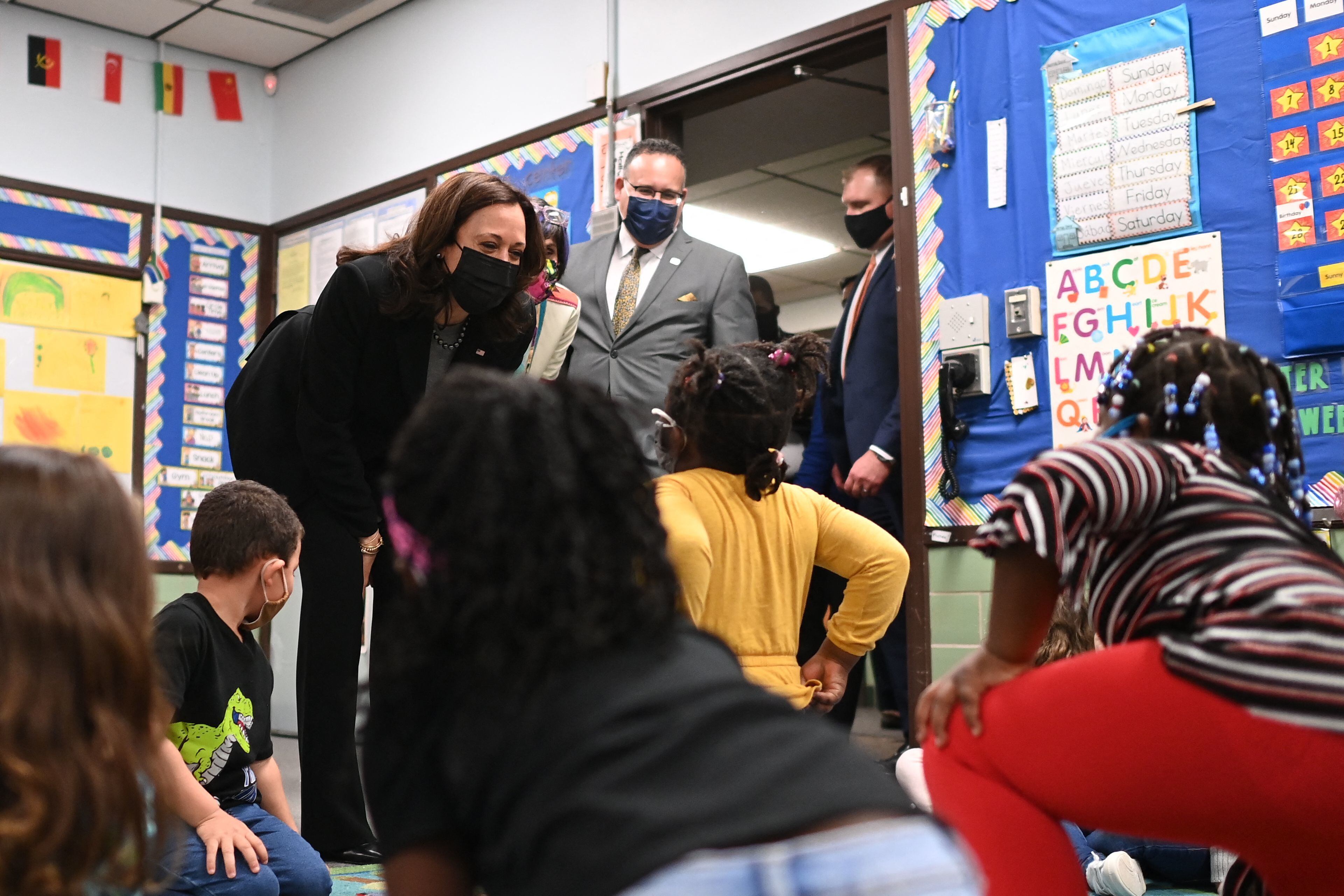

Aside from the grant proposal, the Biden administration has said little else about school segregation or its plans to address it. (Biden himself has opposed federally mandated school desegregation efforts, which drew criticism during the campaign from Kamala Harris, his then rival and now vice president.) Education Secretary Cardona has rarely talked about the issue and he doesn’t plan to mention segregation at an “equity summit” Tuesday, according to prepared remarks.

Over the long term, the department’s Office for Civil Rights will play a key role in determining the Biden administration’s path forward. School integration advocates hope the office will actively enforce school desegregation orders that are still in effect and try to prevent districts from taking steps that would further entrench segregation in their schools. Many see President Biden’s pick to head the office, Catherine Lhamon — nominated last month and not yet confirmed — as an ally.

In the meantime, advocates for school integration say there is more the Biden administration could do beyond its $100 million plan.

One step, they say, would be to reissue the guidance scrapped by Education Secretary Betsy DeVos in 2018 about how school districts can legally consider students’ race in school assignment policies in the wake of the Parents Involved decision. (The decision limited, but did not bar completely, consideration of race.)

Kimberly Lane, who oversees magnet schools for Wake County schools in North Carolina, said that clarity would be welcome. “It’s a real challenge to try to figure out how to do the work in an environment that is legally acceptable and meets the needs of the students and the community,” she said. The district uses magnet schools to help reduce economic segregation. “As districts, we don’t know where the line is.”

For now, the Biden administration won’t say specifically whether it’s working to reinstate that guidance. “We are looking at all of the ways in which we can support schools in achieving racial diversity in their student bodies,” Goldberg said in response to a question about the guidance.

Another idea would be to tie school integration efforts into any new federal spending on education. Biden has proposed spending billions more on school infrastructure and pre-kindergarten, and some integration advocates say districts should be encouraged to build new schools in places that would lead to more diverse student bodies, for example.

“What I’m looking for is a proactive approach that puts integration at the forefront of the spending that is going to happen over the next couple of years,” Lallinger said, “so that we’re not then trying to dig ourselves out of a hole.”

Sarah Darville contributed reporting.