As he continues his push to reopen schools, Education Secretary Miguel Cardona says he is concerned about the students who will choose to learn virtually next year — and about schools using that option for students who would benefit from more hands-on help.

“My fear is that the students that need the in-person the most would be students who would either select or take the fully remote option and not get the supports that they need,” he said during an event hosted by Chalkbeat and The Education Trust. “I would also fear systems that have students who do not fit the traditional mold of how schools are designed being pushed out.”

Cardona said he trusts local officials to make decisions for their communities, and understands that some students thrive in remote settings. But his comments underscore the tensions over who will have the option to learn fully virtually in the fall and which families are more likely to choose that kind of instruction.

While some cities and states are rolling back virtual options, many big districts have said they will continue to offer them, in part due to family demand.

National polls continue to show that Black and Latino families are the most hesitant about sending their children back for full-time in-person learning this fall, and are more likely to consider sticking with remote learning. Asian, Black, and Latino students were the most likely to be learning fully virtually as of April, even as in-person instruction became available in nearly all U.S. schools.

The reasons for that are complicated, but polls have found much of parents’ hesitancy is tied to health and safety concerns. COVID vaccines aren’t expected to be available for younger children until later this year at the earliest, and some parents may want a virtual option until then.

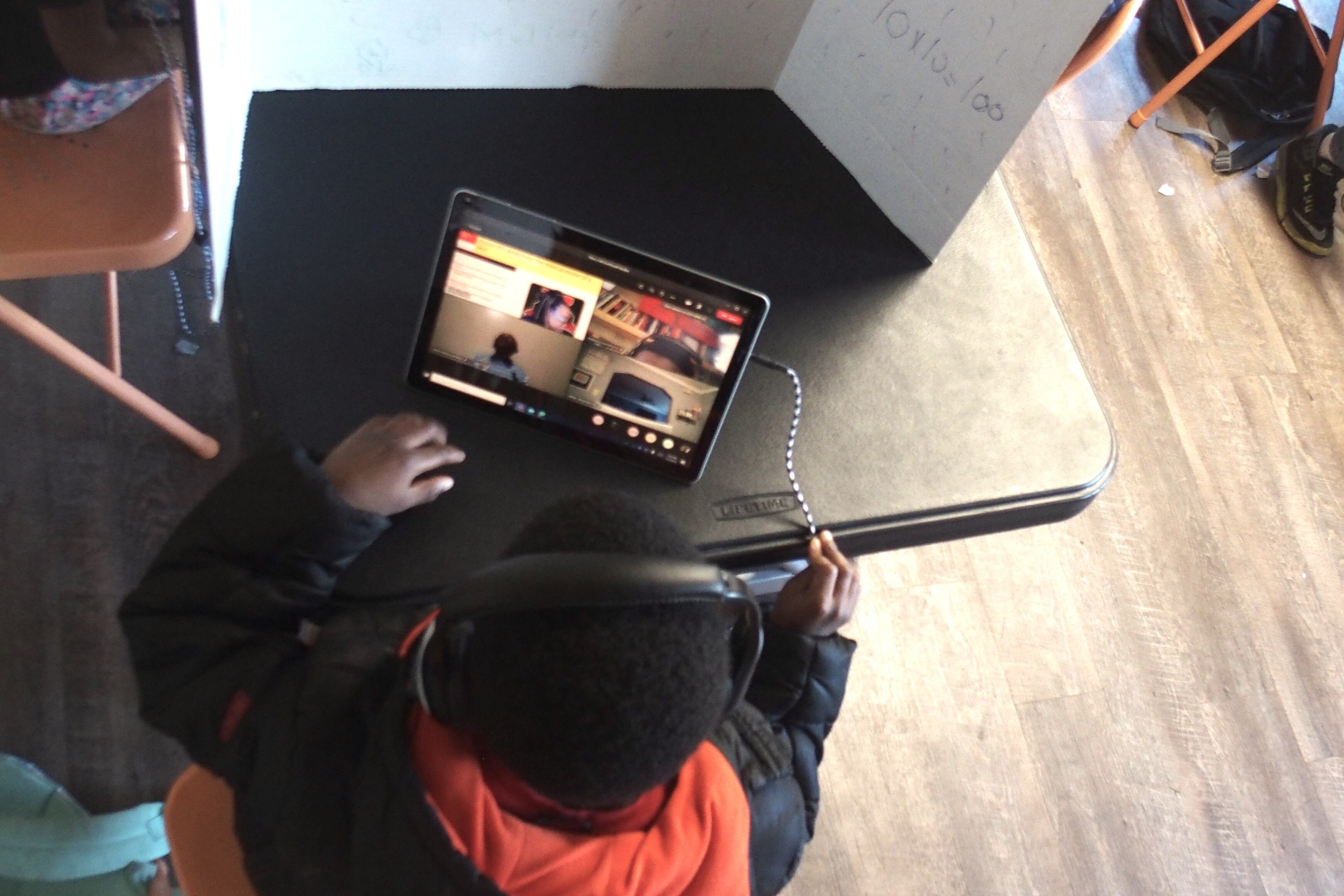

The toll of virtual learning has been well documented, and helps explain why officials like Cardona are worried about the continuation of remote instruction. While some students did well in the virtual setup, many students did not, especially those who had struggled before the pandemic.

Across the country, course failure rates were especially high for Black and Latino students, English learners, and students from low-income families. Students with disabilities and English learners learning fully remotely have had among the lowest school attendance rates nationally. Many students have struggled with the social isolation that can come with attending school online, while others were unable to get critical special education support while school was virtual.

In recognition of that, several school districts and states, including New York City, New Jersey, and Illinois, are planning to nix nearly all virtual options this fall in hopes of getting more students back into school buildings and boosting student engagement.

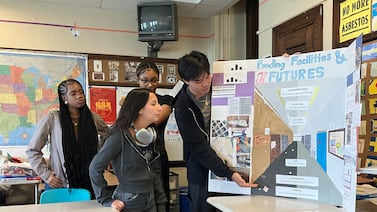

Meanwhile, others planning to offer a full-time virtual option say they’re working to improve that experience. Many will assign students dedicated virtual teachers so educators’ attention isn’t split between a classroom and a screen.

Some education groups are advocating to keep virtual options as a way to provide students with access to additional academic courses or more flexible schedules. Such innovative virtual approaches could benefit some, Cardona said, but full-time in-person learning should be the “default.”

His continued concern, he said, is that some schools might push students who have learning difficulties or emotional needs to virtual options, and that students may choose virtual options because their schools haven’t done enough to address parents’ other worries. Federal education officials have noted in recent reports that Black students historically have been suspended and expelled from school at disproportionate rates, while Asian students have faced an uptick in harassment and bullying during the pandemic.

“I think we’d have to be very careful not to create a system where some students are learning in the schoolhouse and some students that maybe didn’t find the schoolhouse a place where they felt welcome feel that they’re better off not learning in the school,” Cardona said. “That would be detrimental.”