Leer en español.

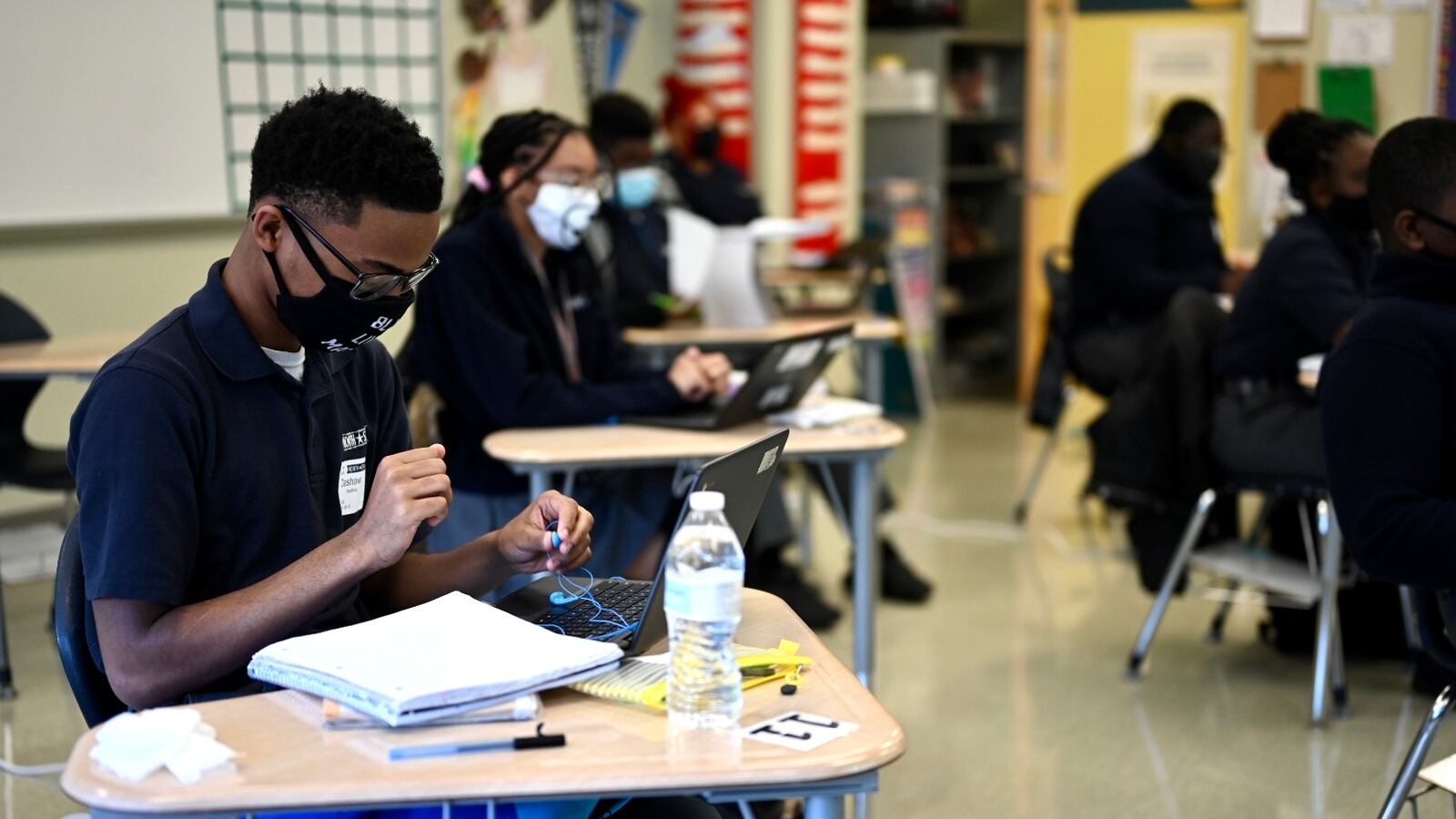

Dashawn Sheffield, a rising junior in Newark, has a soundtrack for the tough pandemic months he has weathered. It’s Mariah Carey.

“Music has always helped me get past my biggest milestones,” Dashawn said. “Funerals, stress, I turn on Mariah. She’s been through a lot in her personal and professional life — she rose above it and went on to accomplish great things.”

In fact, Dashawn was listening to the Mariah Carey song “There’s Got to Be a Way” when he came up with his idea to launch a new student wellness council at his school, North Star Academy Washington Park High School.

He saw the need for more mental health support for his friends after a year of such loss. His neighborhood - like many Black and Hispanic neighborhoods in Newark — was hit especially hard. By this June, nearly 360 out of every 100,000 Newark residents had died from COVID — twice the national average.

Dashawn said he has attended around 19 funerals just in the last year alone.

“It was just so sad, I’d see these people and help them bring in their groceries, ‘’ he said. “Next thing, I’d see an ambulance and their obituaries.”

Dashawn’s story is reminiscent of so many sent to Chalkbeat as part of a project called Pandemic 360, produced in partnership with Univision 41. He was one of more than 275 educators, parents, and students who wrote into Chalkbeat when we asked our readers in New York City and Newark to tell us how the pandemic impacted their schools and neighborhoods.

This series has focused deeply on communities in Newark and New York that managed to shepherd students through challenges big and small — from spotty Wi-Fi to the death of parents. Now, we turn to two students, Dashawn and William Diep — a graduating senior from New York — to tell us how they raised their voices during the pandemic, and why school leaders would be wise to listen to young people during the COVID recovery.

Dashawn Sheffield: We started a student wellness council. Here’s how it has changed the conversation around mental health.

Rising 11th-grader at North Star Academy Washington Park High School in Newark, N.J.

When the pandemic hit, I transitioned from in-person to virtual learning like countless students throughout the nation. We all went from our routines to being inside, staring at computers for eight or nine hours.

My friends and I felt disconnected, and to help alleviate some of the stress, we started talking and helping each other with homework and life. While I felt like I was navigating virtual classes OK, I realized many of my friends were not. Some of us felt depressed and isolated; others struggled to manage ADHD.

I wanted to know more about how my peers outside of my friend group were doing. I sent around a survey, and heard from about 40 people in each grade. I heard again and again about stress, the hard workloads, the fear. I felt like we were all going through the same struggles but we were keeping it bottled up inside.

This is what activated my ambition and drive. I wasn’t really active in my school in student life before the pandemic. After COVID, I wanted to be a student leader. Last summer, I went to my school leaders and proposed the idea of a student wellness council. I wanted students to have a space to process with one another, and for us and teachers to get more training and advice on mental wellbeing.

Our school ended up really listening to us on this. At first I was worried it was all just performative. But in the fall, our school offered a new class on mental health and wellness and our council went into effect.

We now have a student-led space to educate parents, staff, and students on the importance of mental health — increasing awareness around struggles and helping us build resilience. This next school year, we plan on having mental wellness days, one day out of every month geared toward mental health.

I currently live with my godmother — a lot of people around us have passed away sadly. We feel angry and fatigued — and we’re not alone.

Strong education systems are essential to the recovery of students. A school should be at the center of the community and form deep partnerships with the people and businesses of the neighborhood. And every school should work with students to launch a student wellness council.

William Diep: During COVID, students raised their voices. That can’t stop now.

Graduating senior from The Brooklyn Latin School in Brooklyn, N.Y. Incoming freshman at Columbia College.

I remember the first day of my senior year — I had biology and chemistry virtual classes. I was navigating Zoom and the classwork, and feeling totally stressed. I had to do so much on my own — emailing teachers questions that I couldn’t ask in real time and trying to figure out how to write a college essay.

My family tried to be so careful, but my dad still works in the construction industry. We got COVID in the spring in quick succession — my parents and then me. It was a very hard time. I thought about the teacher my school had lost to COVID early in the pandemic. That was such an emotional time for all of us, and here I was with the same illness. Thankfully, my family recovered.

While navigating the pandemic, so many of my friends and fellow Asian Americans are also being attacked. One of my friends was verbally attacked while getting senior photos taken. Our school has an Asian American affinity space that I led this last year. We were able to create and host forums and spaces to talk about how COVID was exacerbating Asian American racism.

And COVID exacerbates so many inequities: Technology disparities, who has Wi-Fi at home, mental health disparities and access to getting healthcare, economic disparities and job loss, vaccine-distribution disparities in Black and brown communities. Where do schools possibly go in the face of all of this? How can we move forward after a year of such hardship?

During this pandemic, there were opportunities like never before for students to raise their voices. Suddenly, people in power were asking us how we were doing and what we needed to succeed. This should have been happening before, but it can’t stop now.

Instead of students reaching out to teachers, teachers reached out to students during the pandemic with suggestion boxes and anonymous feedback forms. They used our feedback in tangible ways. For example: After a survey on wellness, the school created a mentorship program between upperclassmen and underclassmen. They started organizing equity events around race and justice, because we asked for it.

We said that the deadline to submit assignments — which used to be 10 p.m. — should be extended to accommodate students working evening jobs. Someone started a petition to change this, and the school listened. That’s the power of student voice.

Beyond the pandemic, I hope this trend of listening to students and taking our suggestions seriously continues and spreads to every school. There are so many mistakes in our education system, and adult decisions impact students the most. We should be given the most voice.