At the beginning of my freshman year of high school, I witnessed Donald Trump’s ascent to our country’s highest office. For me, it cast a dark and confusing pall over 2016. I had planned to use my education to fight for racial justice. But seeing tens of millions of Americans enthusiastically embrace a presidential candidate who showed no interest in ensuring people who looked like me were treated equally made that plan seem futile.

But as I continued through my high school career, I discovered that my civics classes — like U.S. History, U.S. Government, Comparative Politics, African American History, and Law —reaffirmed my original instincts. Those classes showed me how, even as a young person, I could use political strategies like protesting, writing letters to my elected representatives, volunteering with community organizations, and engaging in get-out-the-vote efforts to address racial injustice.

All Black students deserve the educational opportunities I had. For that to happen, educators need to consider and meaningfully address their Black students’ needs when it comes to learning civics. This is all the more important as states use legislative bans on critical race theory to limit how schools can teach about racism in America. (While most K-12 schools are not actually teaching critical race theory — an academic framework for looking at how laws and institutions perpetuate systemic racism — the term has become a catchall among those who want to block certain teachings about America’s legacy of slavery and segregation.)

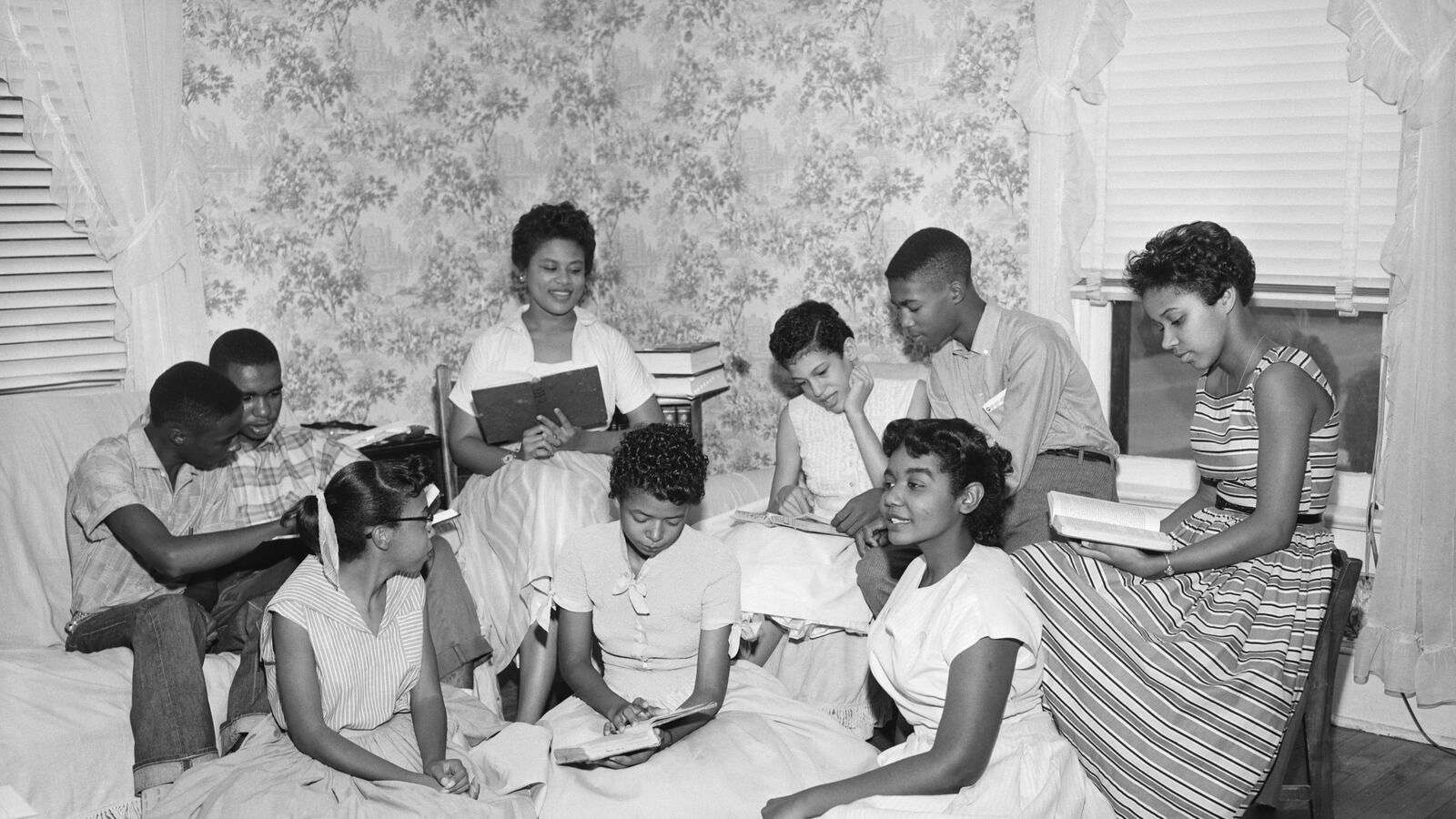

Being attentive to the needs of Black civics students can provide the spark that starts a world-altering social movement. However, neglecting those needs may leave Black Americans ill-equipped to fully participate in politics, which robs our democracy of the diverse voices it needs to prosper. Throughout history, young people have consistently catalyzed some of our world’s most consequential social reforms, and we have young Black people to thank for much of America’s political progress. Claudette Colvin was 15 when she refused to give up her seat on a segregated bus. The Little Rock Nine were teenagers when they put the Brown v. Board of Education ruling into practice. Huey P. Newton was 24 when he founded the Black Panther Party. Marsha P. Johnson was in her 20s when participating in the Stonewall riots that sparked the gay rights movement. Stokely Carmichael (who later adopted the name Kwame Ture) was 25 when he ignited the Black Power movement. At 22, Diane Nash organized sit-ins in Nashville and became a founding member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Today’s anti-racism movement is no different. Like many of my peers, I have been fighting for racial justice in various ways — from registering Black Chicagoans to vote to writing political commentary for my school newspaper. But unlike many of my peers, I have had access to a wealth of political opportunities through my civics classes. Simply taking the classes that I did was a privilege not widely available to other high school students; the opportunities those classes connected me with, such as studying politics and activism in South Africa and interning as a community organizer in my city, were even more selective. Imagine if we were to extend the opportunities I had to all Black students. Just think of the progress we could make.

But beyond its immediate effect, addressing the needs of Black civics students can change the face of our country for years to come. Currently, Black Americans are underrepresented at the highest levels of government and in local offices alike, but a civics education that accommodates the needs of Black students can help to change that. By teaching Black students about active citizenship and encouraging them to explore careers in politics and public service, we can empower students to take their civic knowledge from the classroom to the polls and the halls of government.

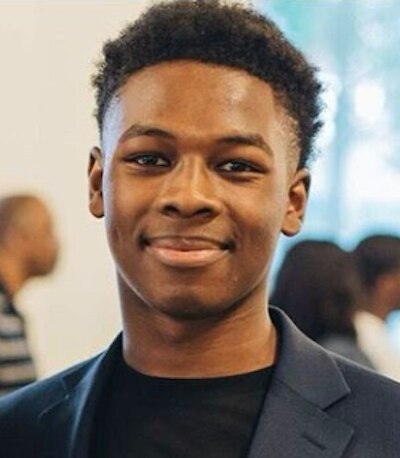

If it were not for my high school civics education, I would not be studying politics at Yale and pursuing a career in politics. And though representation does not equate to progressive change, engaging more Black Americans in our democratic process will create the very diversity of viewpoints that help American liberalism thrive.

But what does it mean to consider the needs of Black civics students?

It means connecting civics topics to relevant real-world issues with the goal of giving Black students practical, actionable knowledge. For example, a lesson on political institutions could prompt a discussion on how America’s governing bodies both uphold and challenge racism. A lesson on elections could focus on current voter suppression efforts or how to be an informed voter in the 21st century. And a lesson about political propaganda could teach students how to assess the credibility of information sources. Unfortunately, some see the act of equipping students with civics knowledge as partisan; as a result, many educators have avoided lessons like these. But Black students (and all students) stand to benefit from classes that teach them how to engage in our democracy.

It also means extending opportunities for political engagement to Black students. Internship programs with local elected officials or activist organizations can expose Black students to how politics works, reinforce the importance of their civics education and give them valuable professional experience. Politicians and political organizations could create internships and fellowships specifically targeting schools serving many Black students. Black civics leaders could develop mentorship programs for Black civics students interested in politics and advocacy. Schools could partner with municipalities to create civics internship programs and then ensure that Black students know about and have ample opportunity to participate.

Because of my civics education, I was able to overcome the feeling of hopelessness that marked the start of my high school career. Now, as a rising sophomore at Yale, I understand the political power I have, and I use it to advocate for justice at my school and in my community. I’m an example of what can happen when we work to meet the needs of Black civics students. It’s past time to invest in this work.

Caleb Dunson is a writer and rising sophomore at Yale.