It’s been a bumpy start to 2022 for America’s schools.

While most schools reopened as planned, at least 4,500 schools closed their buildings for all or part of this week, according to Burbio, a site tracking closures. That makes this week the most disrupted of the school year so far.

Although the closures affected a fraction of the roughly 100,000 American public schools, mostly in the northeast and midwest, they triggered fears of a broader return to remote instruction, seen by many as an educational disaster. That experience has led some school officials to vow to avoid the practice as much as possible.

“What we do in person cannot be replaced,” said Denver superintendent Alex Marrero. “This is not March 2020.”

But school officials are running into a simple but profound constraint: not enough staff due to the surging COVID cases. Even in Denver, 16 schools have temporarily shifted to virtual instruction because too many staff were sick or quarantined.

Meanwhile, national attention is focused on Chicago Public Schools, the country’s third-largest district, where a standoff between the teachers union and the mayor led to the last-minute cancellation of school Wednesday. It was a stark reminder of how local politics is shaping students’ school experience.

Here are some key takeaways from a chaotic and widely varied start of the new year.

Chicago is getting headlines, but its political dynamics make it an outlier.

Chicago Public Schools was shut down Wednesday after a late-night teachers union vote. Almost three-quarters of the rank-and-file members who voted said they preferred to teach remotely until Jan. 18 or until COVID rates fell, prompting the district to cancel classes. School was canceled again Thursday.

Teachers unions in several other cities have expressed similar concerns about school safety as COVID cases rise. In New York City and Philadelphia, for example, the unions have called for a temporary return to virtual learning. But they have not turned to labor action to prevent schools from opening, making Chicago an outlier — as is often the case when it comes to dynamics between the city and its teachers union.

For now, the result is at least 280,000 students out of school and some big unresolved questions, as the union is pushing for a threshold of COVID cases that would pause in-person learning citywide, an approach that city leaders say is unreasonable and health officials say is unnecessary.

Staff shortages remain the central challenge to in-person learning.

The surge in COVID-19 has left schools grappling with a fundamental challenge: Many don’t have the teachers and staff, like bus drivers, that they need to operate smoothly — or at all. More staff are now sick or quarantined, adding to already steep staffing challenges.

“Outside of Chicago and a handful of districts that announced a shift to virtual learning before Christmas, current disruptions tend to be triggered by cases among staff,” Dennis Roche of Burbio wrote in an email update.

In Philadelphia, district leaders had vowed to keep schools open but have moved 92 of the district’s 216 schools to virtual instruction due to staffing challenges. There were simply too many teachers sick, quarantining, or with pending test results, the district said.

Some schools that have stuck with in-person instruction have also struggled with missing staff, making quality instruction a challenge. One New York City high school sent students to the auditorium Monday. In Broward County, Florida, more teachers were out and in most cases the district couldn’t find a substitute, forcing some schools to double up classes.

More students are missing, too, complicating efforts to keep them learning.

New York City has kept nearly all schools open, but student attendance is unusually low — a reminder that even when in-person learning is available, many students still are receiving little or no instruction. About one third of students were absent Monday, and absenteeism rates tended to be higher in schools with more students of color.

Attendance has been relatively low all year in schools across the country, but the problem has grown with more children sick or quarantined and more parents concerned about the spread of the virus.

“There’s not teaching and learning going on anywhere near what you could feel good about as a teacher and educator,” said one Brooklyn teacher, who had raced to post online content for the many students absent Monday.

In Rochester, New York, 40% of students were absent on the first day back. Across Florida, more students were gone too — 23% were missing in Osceola County on Monday, twice what was typical last month, and 18% were absent in Miami–Dade County. In Hartford, Connecticut, nearly a third of students weren’t present.

This could lead to longer-term challenges as teachers try to catch up students who missed class while moving kids who were present forward. The good news: a number of places, including New York City, saw attendance climb a bit on Tuesday.

Many schools still aren’t prepared for virtual learning, and it still doesn’t work for lots of parents.

At schools that returned to virtual learning this week, educators and families experienced déjà vu. Teachers scrambled to post lessons online, parents cobbled together child care, and students dealt with tech glitches that kept them out of class.

In Philadelphia, some families didn’t find out until just before midnight that their child’s school would go remote the next day. In Detroit, some students are still waiting to pick up laptops to access their online classes. Others had a smoother transition. In Newark, the district gave teachers a few days before winter break to hand out work packets and review with students how to log in to their online classrooms in the event of a switch to remote.

“It’s actually going better than I anticipated,” said Alyson Hairston Beresford, a fifth grade teacher who works with students on the autism spectrum. “A few days to prepare makes a huge difference when it comes to my students who have reading difficulties, trouble holding a mouse, and other challenges.”

Parent reactions have been divided, leaving school officials to walk a careful line. Some families say schools should allow remote learning when positivity rates are at record highs, while others say the academic and mental health costs to students, plus the difficulties for parents, are too high to return to online learning for any period.

That division was evident in Detroit, where many parents supported the district’s decision to go remote through mid-January, while others were critical.

“We do put them at risk going to school, but at the same time, I feel kids are better off having school in person just to get the right education and the right needs,” said Ashley Gutierrez, a parent of three children in the district.

In-person learning continues at many schools, though it remains to be seen if more disruptions are coming.

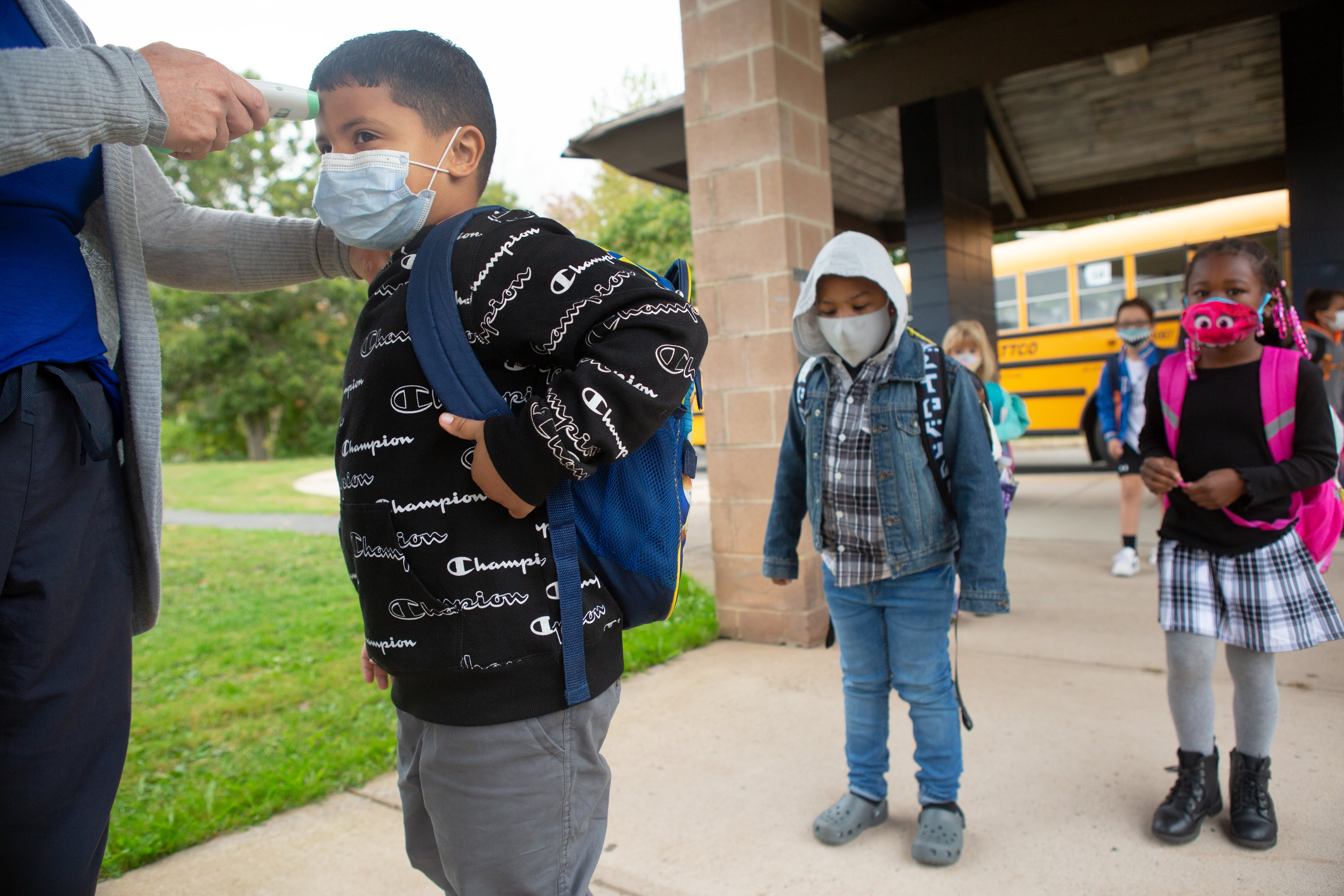

In much of the country, in-person instruction is continuing as usual, though some districts are stepping up mitigation efforts. Some districts where masks were optional are now requiring face masks, while others are encouraging staff and students to wear medical-grade masks instead of fabric ones.

“We have got about 4,000 N95 masks that we just got in that we’re making available to anyone who needs them,” St. Louis schools spokesperson George Sells told the city’s NBC station this week. “Obviously, we would like to see people using the best quality mask that they can.”

In Colorado, where most districts brought students back for in person learning this week, some districts are tightening quarantine rules, while others are relaxing protocols in hopes of keeping more students and staff in school. Denver schools adopted shorter quarantines this week. The district’s teachers union supported the move, though its leaders said they would have preferred if teachers had to present a negative test to return.

“What we don’t want is someone to come back too early and infect others and cause more cases and more closures,” the union’s president said.