Exactly how much did remote learning contribute to students’ academic losses during the pandemic?

A new analysis released Friday inches us closer to a complicated answer.

Using the latest national and state test score data, a team of researchers found that districts that stayed remote during the 2020-21 school year did see bigger declines in elementary and middle school math, and to some degree in reading, than other districts in their state.

But the losses varied widely — and many districts that went back in person had bigger losses than districts that stayed remote. The pattern is inconsistent enough that school closures, it seems, were not the primary driver of those drops in achievement.

“Based on the discussion before these results came out, you’d think that the only thing driving achievement losses would be remote learning, but actually that does not seem to be the case,” said Thomas Kane, a Harvard professor of education and economics who co-led the research. “I was really surprised by these results.”

Earlier research by Kane and others found a strong tie between declines in academic performance and remote learning, which posed huge challenges for students and families nationwide.

The new analysis is the first to look at how the pandemic affected math and reading achievement in many individual school districts. The team relied on testing data for 29 states, spanning around 4,000 school districts that serve some 12 million students in third to eighth grades — or around half of the U.S. student population for those age groups.

Researchers then combined that information with scores released this week from a key national test known as NAEP, which allowed them to compare student performance in spring 2019 and spring 2022. They found that, this year, the students in the median school district had learned about half a grade level less in math and about a quarter of a grade level less in reading, compared with their pre-pandemic peers. (Those conversions of scores to time are inexact, but the researchers say they offer the clearest picture for parents.)

There were drastic differences in performance among districts in each state, they found, with a number of districts actually doing better since the pandemic, a small number doing much worse, and most seeing some declines.

“The pandemic was like a band of tornadoes, leaving devastating learning losses in some districts, while leaving many other districts untouched,” Kane said. “But until now, that damage has been hard to see.”

The research team also found that high-poverty districts suffered greater academic losses, offering a more sobering picture than the national NAEP results did and echoing some earlier pandemic research.

The differences in lost learning between low- and high-poverty districts weren’t large, but were noteworthy, particularly in math. The trend held for reading, though the differences were smaller.

Researchers said math was likely more affected than reading in high-poverty districts — a trend in that subject that’s been widely observed — because school plays a bigger role in how students learn to do math.

These findings, Reardon said, should prompt federal and state leaders to make sure high-poverty schools have the funding and mental health support they need long-term, “so that we don’t end up with a permanently larger amount of inequality than we had before the pandemic.”

How remote learning affected academics

The researchers cautioned that their analysis can’t disentangle the effects of remote learning from other factors. It’s possible the districts that stayed remote longer differed in other meaningful ways from districts that reopened quickly, Reardon said, so researchers will have to do more digging “to really tease out” what happened.

The team will be adding data from more states as it becomes available. Some states that haven’t yet been analyzed, such as Maryland and New Jersey, saw high rates of school closures and big drops in student achievement.

In the coming weeks, the team plans to look at how COVID death rates, internet access, and parent job losses may have contributed to score declines.

“All of those things affected children’s ability to be able to learn,” Reardon said. “So while the remote learning is probably a piece of the story, it’s probably a small piece of all the ways the pandemic affected children’s outcomes.”

The uneven quality of remote instruction likely contributed to the variation in student performance, too.

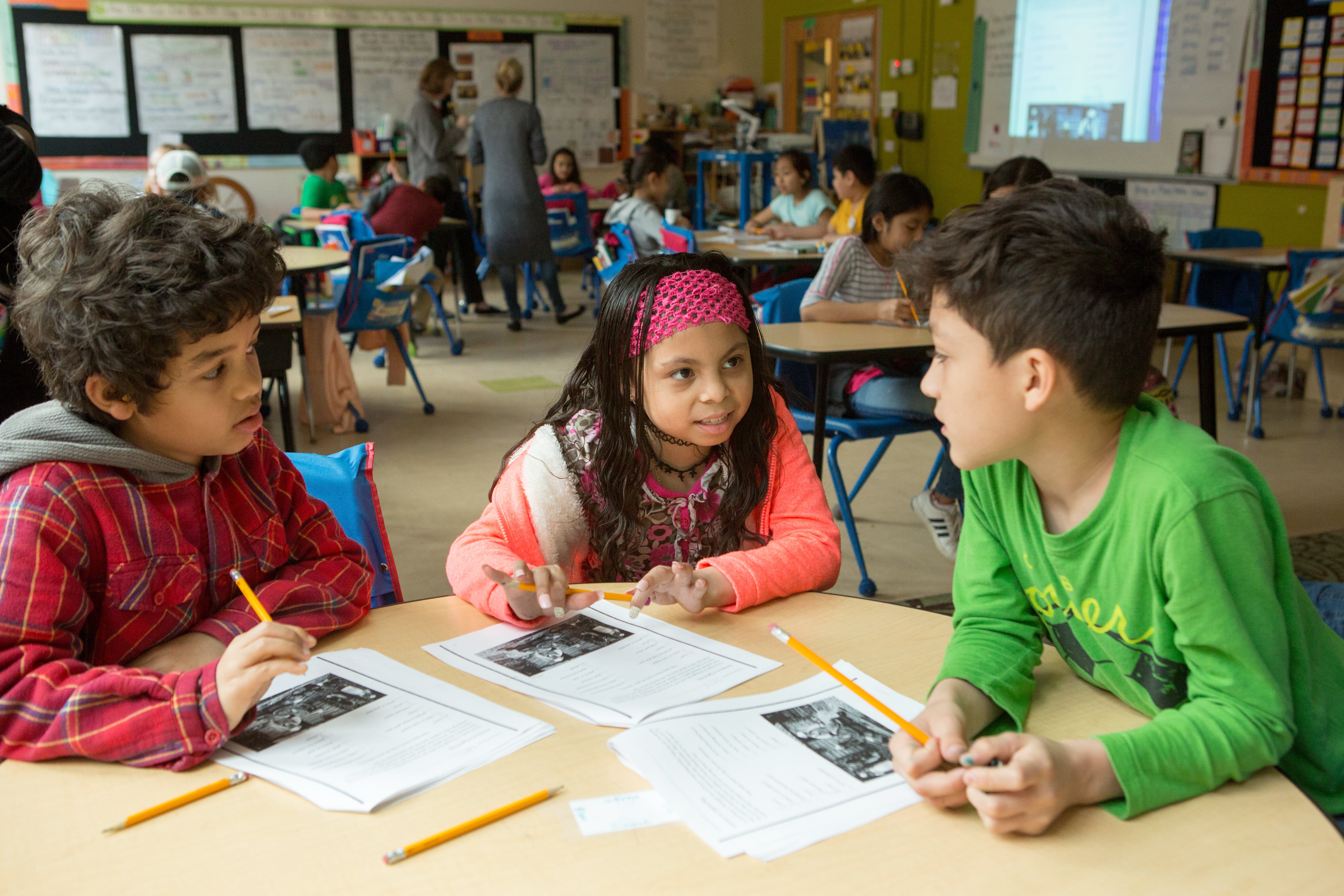

Some students had access to daily live instruction with their teachers, while others spent large chunks of time working on their own, or doing work in paper packets. Students with spotty internet access often weren’t able to watch live lessons and teachers reported that some students logged on while they were working or caring for siblings. Others stopped attending virtual class altogether.

Kane said he hoped their data would urge school districts to beef up their academic recovery plans this spring and summer with strategies like tutoring and extra instruction during vacations — while schools still have time to spend their COVID relief dollars. Too many districts have put smaller efforts in place, he said, that won’t be sufficient to tackle the losses his team found.

“The average kid missed half a year of learning in math, and we’re not going to make up for half a year of learning with a few extra days of instruction or by providing tutors to 5% to 10% of kids,” Kane said.

What he doesn’t want to see is schools waiting to make changes until spring 2023 test results come in sometime next year when they may find: “Wow, kids are still way far behind.”

Kalyn Belsha is a national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.