This article was produced in partnership with the Center for Public Integrity, The Seattle Times, Street Sense Media and WAMU/DCist.

For months, Beth Petersen paid acquaintances to take her son to school — money she sorely needed.

They’d lost their apartment, her son bouncing between relatives and friends while she hotel-hopped. As hard as she tried to keep the 13-year-old at his school, they finally had to switch districts.

Under federal law, Petersen’s son had a right to free transportation — and to remain in the school he attended at the time he lost permanent housing.

But no one told Petersen that.

“They should have been sending a bus for him. … He’s missed so much school I can’t believe it,” Petersen said. “And school is stability.”

A Center for Public Integrity analysis of district-level federal education data suggests roughly 300,000 students entitled to essential rights reserved for homeless students have slipped through the cracks, unidentified by the school districts mandated to help them.

Some 2,400 districts — from regions synonymous with economic hardship to big cities and prosperous suburbs — did not report having even one homeless student despite levels of financial need that make those figures improbable.

And many more districts are likely undercounting the number of homeless students they do identify. In nearly half of states, tallies of student homelessness bear no relationship with poverty, a sign of just how inconsistent the identification of kids with unstable housing can be.

The reasons include a federal law so little-known that people charged with implementing it often fail to follow the rules; nearly non-existent enforcement of the law by federal and state governments; and funding so meager that districts have little incentive to survey whether students have stable housing.

“It’s a largely invisible population,” said Barbara Duffield, executive director of SchoolHouse Connection, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit focused on homeless education. “The national conversation on homelessness is focused on single adults who are very visible in large urban areas. It is not focused on children, youth and families. It is not focused on education.”

Losing a home can be a critical turning point in a child’s life. That’s why schools are required to provide extra support.

Nationwide, homeless students graduate at lower rates than average, blunting their opportunities for stable jobs and increasing the risk of continued housing insecurity in adulthood.

The gap is often stark: In 18 states, graduation rates for students who experienced homelessness lagged more than 20 percentage points behind the overall rate in both 2017 and 2018.

The academic cost is not equally shared. Black and Latino children experience homelessness at disproportionate rates, Public Integrity’s analysis showed. Nationally, American Indian or Alaska Native students were also over-represented, as were students with disabilities.

Until recently, it was not clear from federal records which students were hit hardest by housing instability. Data disclosed in U.S. Department of Education reports revealed nothing about the race or ethnicity of students recognized by their school districts as homeless.

That changed in the 2019-20 school year when the federal government for the first time made public the race and ethnicity breakdowns for individual school districts. The pattern that emerged is a story of the country’s sharp inequities, which put some families at far higher risk of homelessness than others.

The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, first enacted in 1987 and expanded in 2001, requires that districts take specific actions to help unstably housed students complete school. Districts must waive enrollment requirements, such as immunization forms, that could keep kids out of the classroom. They must refer families to health care and housing services. And they must provide transportation so children can remain in the school they attended before they became homeless, even if they’re now outside the attendance boundaries.

Earl Edwards, an assistant professor at Boston College’s School of Education and Human Development, argues that McKinney-Vento was premised on an idea still pervasive in the policy debate on homelessness: Like a tornado that levels towns at random, housing misfortune has an equal chance of afflicting anyone, regardless of who they are.

In the 1980s, that rhetoric was a potent argument in favor of expanded federal support for homeless services. It was also wrong.

The McKinney-Vento Act started as an inadequate policy

The McKinney Act — later renamed — took shape at a time when the Reagan administration, if it acknowledged homeless people at all, regarded them as having chosen a life on urban skid rows, said Maria Foscarinis, who helped write the law.

Foscarinis, the founder of the National Homelessness Law Center, reframed homelessness as a broader structural problem impacting families, people of all races, even suburbanites. The outcome was a race-neutral solution, despite data at the time that went counter to that theory.

Foscarinis said the law’s architects knew it was inadequate and planned to follow it with homeless prevention programs and housing. But they faced stiff resistance. It would have been better to include race-conscious language tracking the demographics of homeless children, she added, but doing so could have jeopardized the entire effort.

“Had we done that, it would have torpedoed the whole thing, which would have hurt Black communities even more,” she said. “Then, we would have nothing at all.”

Figures now available down to the school district show the consequences of homelessness policy that doesn’t address race directly.

Nationally, Black students were 15% of public school enrollment but 27% of homeless students in 2019-20. In 36 states and Washington, D.C., the rate of homelessness among Black students was at least twice the rate of all other students that year.

Boston College’s Edwards said the disconnect lies between the reality of housing inequality and the policies intended to address it.

“If you don’t recognize that Black people, during the time when you were establishing the actual policy, were disproportionately experiencing homelessness” — and that housing discrimination, urban renewal, blockbusting and other systemic factors pushing Black people out of housing were key drivers — “then you make a policy, and the policy doesn’t have anything in place to prevent those things from persisting,” Edwards said.

And under-identification of homelessness could impact Black students more than peers of other races.

In interviews with Black students who experienced homelessness while enrolled in Los Angeles County public school districts, Edwards found that many distrusted school personnel, who underestimated their academic ability, sent them to the principal’s office for the smallest perceived slights, and threatened to call child protective services.

As a result, Edwards found, many students went unidentified under McKinney-Vento because they feared that sharing their situation would only make things worse. They paid for transit passes out of pocket. They were forced out of their home districts. They navigated college admissions alone. If they were lucky, they found mentors outside of the school system.

Those experiences aren’t an accident, Edwards argues, but the product of historical patterns. For example: “Calling child protective services would not be a severe threat to Black students if racial disparities within the institution itself were less pronounced.”

Beneath the race-neutral veneer of McKinney-Vento, American Indian or Alaska Native students and Latino students also experience housing instability at higher rates than their peers in the majority of states.

In Capistrano Unified, a 44,000-student school district in southern California, the rate of homelessness among Latino students was roughly 24% in recent school years compared to about 2% among the rest of the student body.

“It’s not anything that we’ve really done research on, so I wouldn’t even be able to speculate” as to why, said Stacy Yogi, executive director of state and federal programs for the district.

Across California, Latino students are 56% of public school enrollment but 74% of homeless students.

A 2020 report from the University of California, Los Angeles, found that Black and Latino students who experience homelessness in the state are more than one and a half times as likely to be suspended from school as their non-homeless peers. They also miss more school days and are less prepared for college.

Public Integrity’s analysis also found that students with disabilities have higher rates of homelessness than the rest of their peers in every state except Mississippi, suggesting that a significant share of students who already require additional support attend school uncertain of where they will sleep that night.

“They’re experiencing trauma, and trauma has a pretty significant impact,” said Darla Bardine, executive director of the National Network for Youth, a policy and advocacy group focused on youth homelessness. “You have to navigate an overly complicated system, and it’s this competition for limited resources where young people and children and families are just inherently disadvantaged.”

EJ Valez, who has limited vision and requires large-print materials for reading and braille instruction, was among them.

Valez experienced housing instability for most of his youth, bouncing between homes and schools in the Bronx and Reading, Pennsylvania.

“I’m surprised I made it out of school,” he said.

As a teenager, he said, he couch-surfed with friends and acquaintances after he became estranged from his family.

“Somehow I could retain information, but at no point in my childhood before full-on adulthood was there ever actual stability,” said Valez, now a student at Albright College in Pennsylvania and a member of the National Network for Youth’s National Youth Advisory Council. “No one cares about classes if we don’t know where we’re going to put our heads at night.”

That, he said, is why extra help from schools is so critical.

Hidden homelessness in America

It might seem like common sense to assume that where more children experience poverty, more will experience homelessness, too.

But that’s not what the data from school districts show. One of the most surprising patterns we found is that reported homelessness among students didn’t mirror poverty in 24 states.

The finding runs counter to a growing body of empirical evidence supporting the connection between poverty and housing instability. Children born below 50% of the poverty line had a higher probability of eviction than higher-income peers, lower-income households are more likely to experience forced mobility, and renters who are forced to move end up in higher-poverty neighborhoods than renters who move voluntarily.

“There should be a stronger relationship between homelessness and poverty,” said Jennifer Erb-Downward, director of housing stability programs and policy initiatives at the University of Michigan’s Poverty Solutions, “and the fact that there’s not supports that there’s under-identification taking place.”

Districts can tell teachers and staff to look for common signs of housing instability among students — fatigue, unmet health needs, marked changes in behavior. But those aren’t always apparent.

If they’re following the law, districts will survey families so they can self-identify as homeless. But some parents fear that acknowledging their housing struggles could prompt the government to take their kids away.

And then there’s the gulf between what people commonly think of as homeless and the more expansive definition Congress uses for students. Living in a shelter, on the streets, in a vehicle or in a motel paid for by the government or a charitable organization are included, but that’s not all.

More than 70% of children eligible for services were forced by economic need to move out of their homes — with or without their family — and in with relatives or friends, a practice that the U.S. Department of Education defines as “doubled up.”

Research on doubled-up students shows there’s good reason to provide them with help: They earned lower grades, for example, and were less likely to graduate on time.

In Riverside County, California, Beth Petersen’s son met the definition of doubled up for months, having lived temporarily with her sister and with friends.

Only Petersen didn’t know it at the time.

Eventually, the two found housing outside the Temecula Valley Unified School District her son had attended for years. He switched districts, keeping up with the schoolwork but struggling to make friends.

Then a friend of Petersen’s who works at a charter school told her that her son had the right to re-enroll in the Temecula Valley schools because the McKinney-Vento law allows students to stay in the same school they attended before becoming homeless.

In early September, Petersen moved with her son into a two-bedroom apartment — still outside the district boundaries — paid for by a homeless prevention organization and shared with another family. Under federal law, her son is considered homeless because they live in transitional housing.

Petersen re-enrolled her son in Temecula Valley Unified but problems persisted. She said she pleaded with the district for weeks, trying to secure bus rides for the teenager. The district never responded to her emails, she said. He ultimately missed a month of classes, Petersen estimated, because she could not afford to continue paying acquaintances to transport her son every day.

The California Department of Education intervened in late September to ensure her son received transportation.

“This has been a teachable moment for the district and there are protocols and … barriers that have been removed to ensure the law is met,” an employee at the state agency wrote Petersen in an email.

A statement provided by Temecula Valley Unified in response to detailed questions regarding the Petersens said the district “does everything in its power to support our McKinney-Vento families experiencing homelessness” and has “highly responsive site and district teams,” but declined to comment further.

Experts think students like Petersen’s son are among those most likely to go unidentified and unassisted because their families don’t realize they qualify for help and schools too often fail to fill the information gap.

When that happens, “we’re not even including most of our kids who are experiencing homelessness in the definition of who’s homeless,” said Charlotte Kinzley, supervisor of homeless and highly mobile services for the Minneapolis Public Schools. “So we haven’t even named the problem.”

In Minneapolis, the reported graduation rate for homeless students is at least 26 percentage points below the rate for all students. The district introduced programs in the last few years to help schools find more students experiencing housing instability and connect them with assistance. Lesson plans for teachers help high school students understand if they qualify.

Across Minnesota, districts generally reported homeless rates that loosely mirrored trends in free- or reduced-price lunch eligibility, suggesting some consistency in identification.

“It’s not a matter of getting the right count or getting the numbers,” said Melissa Winship, a Minneapolis schools counselor who works with students experiencing homelessness. “It’s a matter of those students and families having those supports and resources that they deserve.”

Data on student homelessness is collected by districts and funneled to the federal government by states, which can choose to leave out any districts that did not report having any homeless students. Our data adds those excluded districts back. We assume they identified no homeless students, since they’re not in federal data.

Our analysis focused on non-charter districts in the 2018-19 and 2019-20 school years. In addition to comparing poverty and reported homelessness, we applied a common benchmark used by education researchers and some public education officials — that one of every 20 students eligible for free- or reduced-price lunches experience homelessness under the federal definition.

In each school year we analyzed, more than 8,000 districts did not meet the one-in-20 guideline.

DeSoto County, Mississippi, for instance, identified fewer than 300 homeless students, according to state records Public Integrity reviewed. Its share of students eligible for free- or reduced-price lunches suggests the district has three times the number it reported.

That’s not the only reason to suspect an undercount. In 2018, local landlords filed more than 4,000 eviction cases, according to an estimate from Princeton University’s Eviction Lab.

By comparison, Mississippi’s Vicksburg Warren School District identified about as many homeless students as DeSoto despite having less than half as many children eligible for free- or reduced-price lunches.

The DeSoto County schools did not respond to requests for comment.

It’s possible that some school districts genuinely have fewer homeless students than this benchmark predicts. But multiple researchers told us that they see the one-in-20 threshold as a conservative estimate.

J.J. Cutuli, a senior research scientist at Nemours Children’s Health System, said the analysis bolsters the anecdotal experiences of school district staff, shelter personnel, and people who’ve lived through periods of homelessness.

“You’re giving us a clue as to the magnitude of this problem. And that’s really the important part here,” he said.

The University of Michigan’s Erb-Downward said the reason numbers are critical is because “we, somehow, as a society, have agreed that it is OK for the level of poverty and instability that children experience, from a housing perspective, to exist.”

“If we don’t actively track that, and have a conversation about what the level [of homelessness] really is, I don’t think we’re being forced to actually look at that decision that we’ve made societally,” she said. “And we’re not really being forced to say, ‘Is this actually what makes sense? Is this actually what we want?’”

Why tracking homeless children in America is an ‘uphill battle’

The federal government, state education departments, and families have few options to hold districts accountable if they fail to properly identify or provide assistance for students experiencing homelessness.

The U.S. Department of Education delegates enforcement to states. States where school districts fail to follow the law are subject to increased monitoring, but the federal agency would not say how often that happens. A spokesman said only that the agency “engages in monitoring and compliance activities that can include investigating alleged non-compliance.”

Public Integrity reviewed dozens of lawsuits in which families and advocacy groups alleged that school districts denied students rights that are guaranteed under the federal McKinney-Vento law.

Families experiencing homelessness have sometimes prevailed in their standoffs with education agencies, winning reforms like agreements to train school personnel in the law and, in one case, a toll-free number for parents and children to contact with questions about their rights.

“There’s not really a ton of capacity for actually investigating and dealing with these complaints,” said Katie Meyer Scott, senior youth attorney at the National Homelessness Law Center. “We have a problem where there’s not necessarily an investment in enforcement at either the federal or state level.”

As an extreme last resort, the U.S. Department of Education can cut funding — a step officials are loath to take because that would ultimately harm the very students the agency wanted to help. The agency said it has never penalized a state in this manner.

A 2014 investigation by the Government Accountability Office found that eight of the 20 school districts its staff interviewed acknowledged they had problems identifying homeless students. The watchdog agency found that the U.S. Department of Education had “no plan to ensure adequate oversight of all states,” with similar gaps in state monitoring of school districts.

State audits in California, Washington, and New York have also made the case that many school districts fail to identify a significant number of students who qualify for the rights guaranteed under federal law. Advocacy groups and researchers, too, have surfaced examples.

In Michigan, state Department of Education guidelines call for an investigation if school districts identify fewer than 10% of low-income students as homeless. Erb-Downward found that all but a handful of Detroit schools fell below this threshold in the 2017-18 school year.

Public Integrity’s analysis points to similar problems. Detroit’s public school district, the largest district in the state, identified 255 fewer homeless students than the Kalamazoo Public Schools in 2018-19, despite having four times as many students and a much higher poverty rate.

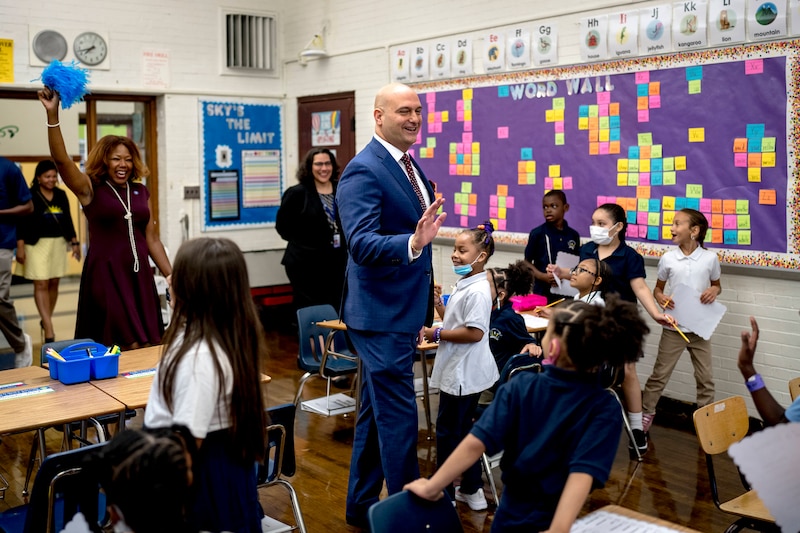

Detroit school superintendent Nikolai Vitti said in a statement that the district’s efforts to improve in recent years include adding full-time staff to its homeless student office, a residency questionnaire with its student enrollment form, referral systems, and public information about available services.

Homeless student numbers have tripled in the past several years, Vitti said. But, he added, “We are aware there is still an undercount.”

A statewide review this year identified 120 Michigan school districts, roughly 20%, in need of additional monitoring, department spokesman Martin Ackley said. The state is asking those districts to provide evidence that they are in compliance with federal law.

The state expects to finish the reviews this winter and will provide technical support to districts struggling to meet federal requirements.

Districts in other parts of the country willing to explain likely undercounts offer a variety of reasons.

In the Chester-Upland School District outside of Philadelphia, interim homeless liaison Dana Bowser said many families consult district staff as a last resort when they can’t find a solution to their housing troubles on their own. Language barriers make some parents reluctant to come forward, she added.

Florida’s Broward County Public Schools described struggles to overcome limited funding, stigma, and fear of immigration services as “skyrocketing home prices and lack of regulation around rental fees have created an unfortunate climate in which more individuals and families are facing homelessness, including middle-class income families.”

And in the Yuma Union High School District along Arizona’s borders with both California and Mexico, where our benchmark predicted more than five times the number of homeless students than was reported in the 2019-20 school year, school officials said they do not report a child as homeless if they do not apply for and receive services under McKinney-Vento. The National Center for Homeless Education advises officials to count enrolled homeless children and youth even if they decline services available to them.

In Oklahoma, hundreds of districts report that no students experience homelessness. Tammy Smith, who oversees the state’s homeless student programs, hears a common refrain from school leaders when she asks why.

“They tell me, ‘We’re going to take care of all of our students, whether we identify them as homeless or not,’’’ Smith said. “I remind them it’s federal law, but it’s kind of [an] uphill battle.”

Leaving homeless children out of official records is a problem even if a district does manage to support them without properly counting them, said Amanda Peterson, the director of educational improvement and support at the North Dakota Department of Public Instruction.

“If we are not able to tell the story, we’re not able to show that there’s discrepancies in the graduation rate, then what ends up happening is that it’s easy for legislators, community members, others to just close their eyes to the issue and just say, ‘Well, if it’s not reported, it doesn’t exist, and therefore we don’t need to worry about it,’” she said. “There’s harm if we just sort of push it under the rug.”

‘Not enough money’ to support homeless students

Federal programs provide school districts little financial incentive to survey students’ housing situations more thoroughly. Money to serve these vulnerable children is limited and does not increase automatically as districts identify more of them, Public Integrity found.

Instead, the U.S. Department of Education awards funds to states using a formula that factors in poverty rates. States use their share to award competitive grants to districts.

Calling them paltry is an understatement.

The funding amounted to about $60 per identified homeless student nationwide before the pandemic. One state received less than $30 per student.

That’s a fraction of what school districts actually spend to support homeless students, according to a recent study by the Learning Policy Institute, a nonpartisan research group. The four districts profiled by LPI spent between $128 and $556 per homeless student identified. In two of those districts, McKinney-Vento subgrants accounted for less than 14 cents on every dollar the district spent on homeless education programs.

And that’s the districts awarded federal grants. Most get nothing.

Until a temporary funding influx during the pandemic, only one in four districts nationwide received dedicated funding. Washington state, which got the lowest amount in the 2018 fiscal year at $29 per identified student, passed a law in 2016 to provide additional support and resources.

“I would argue that a state like Washington has better identification, but it’s not reflected in how the feds dole out the money from McKinney-Vento,” said Duffield of SchoolHouse Connection.

Even in states that receive hundreds of dollars per student, the money does not stretch far, experts said. And it’s definitely not enough to provide long-term assistance for students without stable housing.

One sign of its inadequacy: Many districts don’t even bother applying for the federal money. In Oklahoma, just 25 of the state’s 509 districts requested funds.

Smith, who oversees the state’s homeless student programs, urges districts to apply. She said superintendents tell her, “There’s not a monetary benefit for us to identify them. So that’s not where we’re spending our time.”

In 2021, the American Rescue Plan made $800 million available to states and districts to identify and support homeless students, some of whom became disconnected from schools after the COVID-19 closures of 2020. The historic funding influx was seven times the annual budget awarded to schools to support their homeless students in 2022, making federal funds available to districts that had not previously received money.

In Wayne County, Michigan, where Detroit is located, the additional funding was sorely needed, said Steven Ezikian, the deputy superintendent of the Wayne County Regional Educational Service Agency, which helps train local districts to identify and support students experiencing homelessness.

“McKinney-Vento does not provide nearly enough funding,” he said. “Frankly, there’s just not enough money for them to do all the work for the amount of kids that we have.”

The traditional level of funding to support homelessness has left many districts struggling to fulfill the law’s requirements.

“There [are] more and more students in crisis and the districts are not really getting more and more resources to help,” said Scott, the senior youth attorney with the National Homelessness Law Center. “It comes down to resources rather than any kind of bad intent. The lack of investment in our schools over time is obviously hitting homeless students even harder.”

In April, 92 members of the U.S. House of Representatives signed a “Dear Colleague” letter, urging the chairwoman and ranking member of the House Education Committee to renew the $800 million in funding, which represents 1% of the federal education budget, for the fiscal year that started Oct. 1. It would be money well spent, they argued.

“Investing in a young person’s life will enable them to avoid chronic homelessness, intergenerational cycles of poverty, and pervasive instances of trauma,” the letter read.

Budget bills from both chambers of Congress requested boosts in the program budget that are far short of what the House members requested. Federal budget negotiations will likely resume in December.

Temecula Valley Unified, the district Beth Petersen’s son attends, received $56,000 to serve homeless students through the American Rescue Plan — about $470 per homeless student identified. District staff did not respond to questions regarding funding for homeless education programs. State financial records for the several years before the American Rescue Plan show the district received nothing.

Early on a Monday morning in October, Petersen sat at the kitchen table in her shared apartment, applying makeup under the glare of a bowl-shaped ceiling light. Her son emerged from the bathroom, barefoot but otherwise dressed for school. Petersen peered around the corner. Did he want anything for breakfast? He shrugged. No, he was fine.

But then he remembered an assignment that was due: a photo with his mom clearing him to attend a sexual education course. He stooped beside her and angled his laptop for a selfie. Beth could hardly remember the last time she needed to review any of his assignments. He was always a diligent student, even these last few months.

“Do not miss the bus coming home or we will be up a creek,” she said as the pair walked outside, the air crisp as morning haze yielded to blue sky.

At 7:02 a.m., a yellow school bus turned the corner. It slowed to a stop before them, the fruits of Petersen’s long struggle to make the promise of the McKinney-Vento law a reality.

The doors opened, and her son was on his way.

Chalkbeat journalist Lori Higgins contributed to this article.

Amy DiPierro and Corey Mitchell are journalists with the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates inequality.