Teacher Kim Meaders has a singular focus when she steps into her Arkansas school just before 7 a.m.: keeping her school’s eighth and ninth graders from falling off track.

Meaders, a math teacher at Bryant Junior High in suburban Little Rock, is part of the Arkansas Tutoring Corps, which launched last year with federal COVID relief funding to help students plug pandemic learning gaps.

Since the fall, she’s been meeting with small groups of students at lunch or before school, helping them master two-step equations and memorize exponent rules.

“It’s definitely helping,” she said. Students who were afraid to ask questions in class are speaking up in tutoring. “That’s what was important to me, to make sure that the kids didn’t get farther behind,” Meaders said. When they do, she can prevent students from getting frustrated and giving up.

“Math is such a progression,” she said. “If we don’t address those issues quickly, it just compounds the problem.”

The Arkansas initiative is just one of at least a dozen new large-scale tutoring efforts started by state education departments and school districts across the country. They’re part of an unprecedented effort to help students recover academically after two years of disrupted schooling.

There are encouraging signs: Thousands of tutors like Meaders have gotten to work, and some say they’ve seen students make progress. But several initiatives are starting smaller or taking longer to reach students than officials originally hoped.

Chicago, for example, wanted 650 tutors in its corps this year, records show, but has 460. New Mexico hoped to place 250 “educator fellows” in schools this spring, but has 100 in schools so far. Arkansas wanted 250 tutors in place by winter, but has 219.

School officials are working hard to fill those slots. But the gaps are an indication of just how many students aren’t yet getting the help that officials think they need.

“The need was huge,” said Missy Walley, who’s overseeing Arkansas’ tutoring effort. The state has some 570 tutors in the pipeline, more than its goal, though 350 are still completing training and background checks. “We’re going to meet that.”

Smaller programs that rely on virtual tutors have gotten closer to their targets. Oklahoma, for example, wanted to bring on 250 virtual math tutors this winter and hired 210. State schools chief Joy Hofmeister said families reported on surveys that the tutoring had helped their eighth graders bring up failing grades and boost their confidence in math.

Other efforts still have a ways to go. In Houston, officials wanted to have 500 high school and college students tutoring in schools by now. They have 228 so far. That means the elementary schools they targeted for extra help have around four tutors per building, instead of the planned-for 10. (The district also has a separate pool of teacher tutors.)

Illinois education officials won’t say how many tutors they’ve hired so far, but the state pushed back the full launch of its initiative from this spring to next fall. Officials are looking for some 8,700 in-person tutors statewide — a much more ambitious goal than others have set.

“We’re certainly, as would be true in other states, experiencing challenges with staffing,” said Stephanie Bernoteit, a state official working on the initiative. “This type of project is fairly easy to describe. It is incredibly complex to implement.”

Dallas has turned to outside organizations to hire the 665 tutors who are helping students or are about to be assigned a school. Many are local, but some work virtually, Zooming in from as far as Montana. The district also has more than 40 additional tutors of its own on staff, though it is trying to get to at least 70.

“People are excited to have tutoring up and running — they know that students need it,” said Derek Little, the district’s deputy chief of teaching and learning.

Getting there, though, has required competing for tutors in a tight labor market.

Chicago, for example, was trying to recruit tutors at the same time as the school district was looking for substitute teachers and bus aides, positions with similar requirements and pay. It got to 460 tutors this month, and is looking to reach 600 by the fall.

Officials think they can get there with a refined recruiting strategy. They’ve learned to pursue candidates who are more likely to pan out: community members recommended directly by school principals and college students studying education.

Geography has posed another challenge. Tennessee’s tutoring initiative is ahead of schedule — they have more than 2,000 tutors working across 71 school districts, said Penny Schwinn, the state’s education commissioner — but rural school districts have had a harder time recruiting.

“Our very rural communities have struggled the most, especially if they’re doing after-school specific programs,” Schwinn said. Education officials are now meeting with rural districts to help them incorporate tutoring into the school day, a setup that can make it possible for more parents to serve as tutors.

In New Mexico, recruiting educator fellows has been easier than expected, said Amber Romero, who is overseeing the program. That’s in part because paraprofessionals and classroom assistants want these jobs, since the fellowship offers benefits and a stipend they can use toward a degree in education.

The interest has prompted some districts to delay their programs until the fall, when they will have backfilled those assistant roles. The fall start will also allow districts to hire high school seniors who are graduating this spring.

Scheduling remains a persistent challenge, too. Schools want tutors during the school day, several times a week — when they’re often shown to be most effective — but it can be hard to get tutors at that time.

William Solomon, who oversees the student tutor corps for Houston ISD, says it’s been difficult to get everyone’s schedules to line up as they try to match high schoolers and college students with younger peers.

“I definitely want to make sure that we’re starting earlier, and that we’re tapping into as many of those college students who want to test drive this career in education as possible,” Solomon said. “This is not something that’s going away, so the need for these near-peer tutors is going to continue.”

Another issue: It’s unclear whether the tutoring that is happening is truly helping students who’ve fallen the furthest behind. While all eight state and district initiatives that Chalkbeat spoke with for this story are keeping tabs on student progress, none had data to share yet.

Some initiatives have found that reaching students who most need help can be a challenge, especially if tutoring is optional and happens outside the school day.

In Oklahoma’s tutoring trial run, for example, just over a quarter of the 481 eighth-grade students who got extra help in math had been asked to attend tutoring based on their low test scores. The rest signed up on their own. As the state tries to expand to more grades, officials say they plan to reach out to targeted students earlier and more often.

Tutoring initiatives have faced logistical hiccups, too. In Chicago, the district recruited tutors before it finalized which companies would train them and provide them with tutoring materials. Officials thought they had a better chance of keeping tutors on staff if they paid them sooner. Plus, putting them into buildings quickly helped them build relationships.

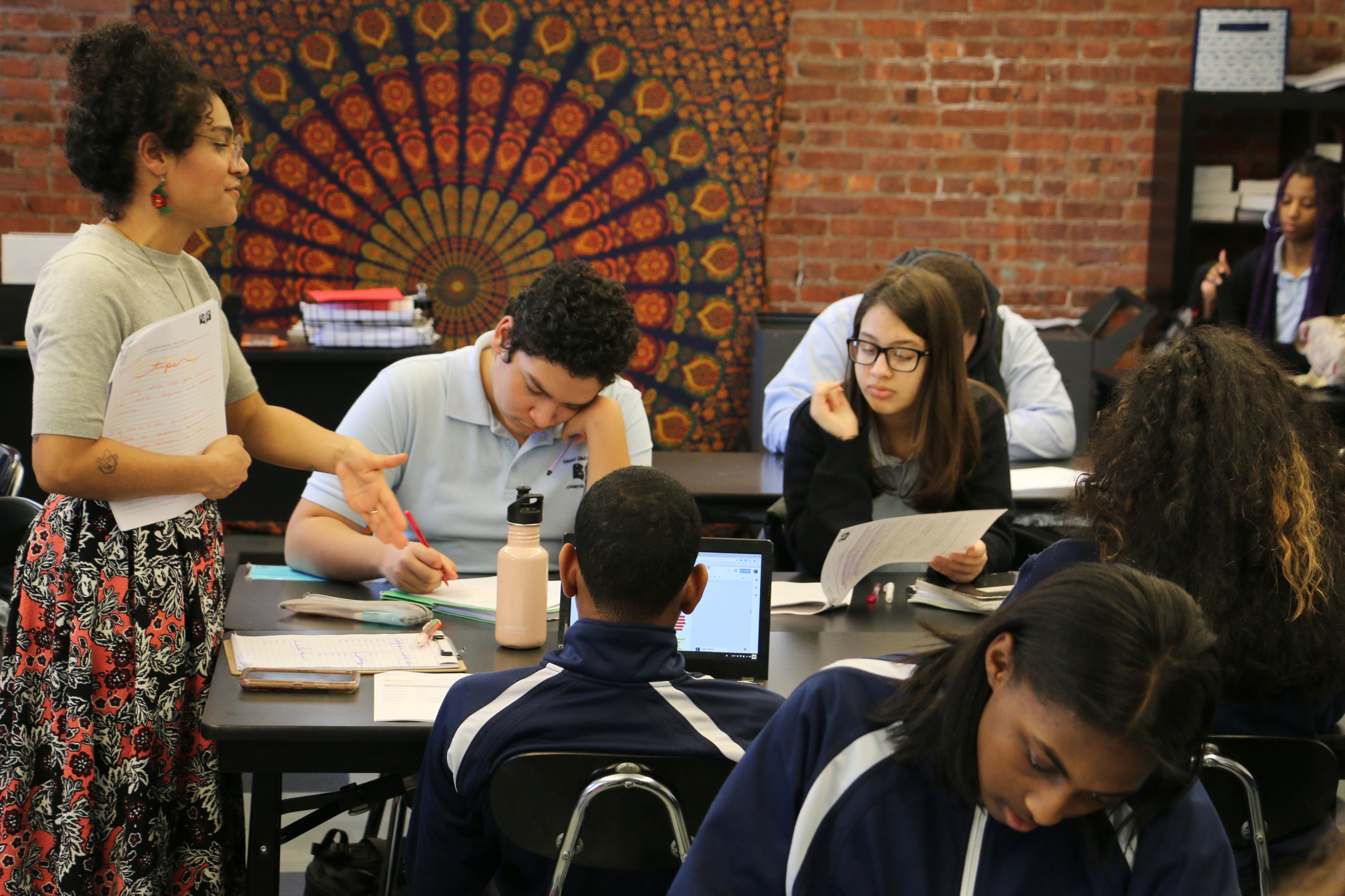

But that left tutors like Darrell Hill, who started tutoring Chicago high schoolers in math this fall, to improvise. Tutors made up practice problems and tracked student progress informally.

All tutors eventually got trained, and Hill and other tutors now have lessons that correspond with what teachers are working on, along with a ready set of practice problems.

Hill and the three other tutors at his school have come up with their own routines, too. They all attend a morning math class together to make sure they understand that day’s lesson, grab copies of upcoming assignments, and then compare notes. Then they work through assignments and homework with students, who are seeing the benefit.

“We’re hearing initially ‘Don’t want to be here, this sucks, I want to go have lunch with my friends,” Hill said. But that turns into: “‘OK, now I get it. I didn’t get this before, now I do.’”

Kalyn Belsha is a national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.