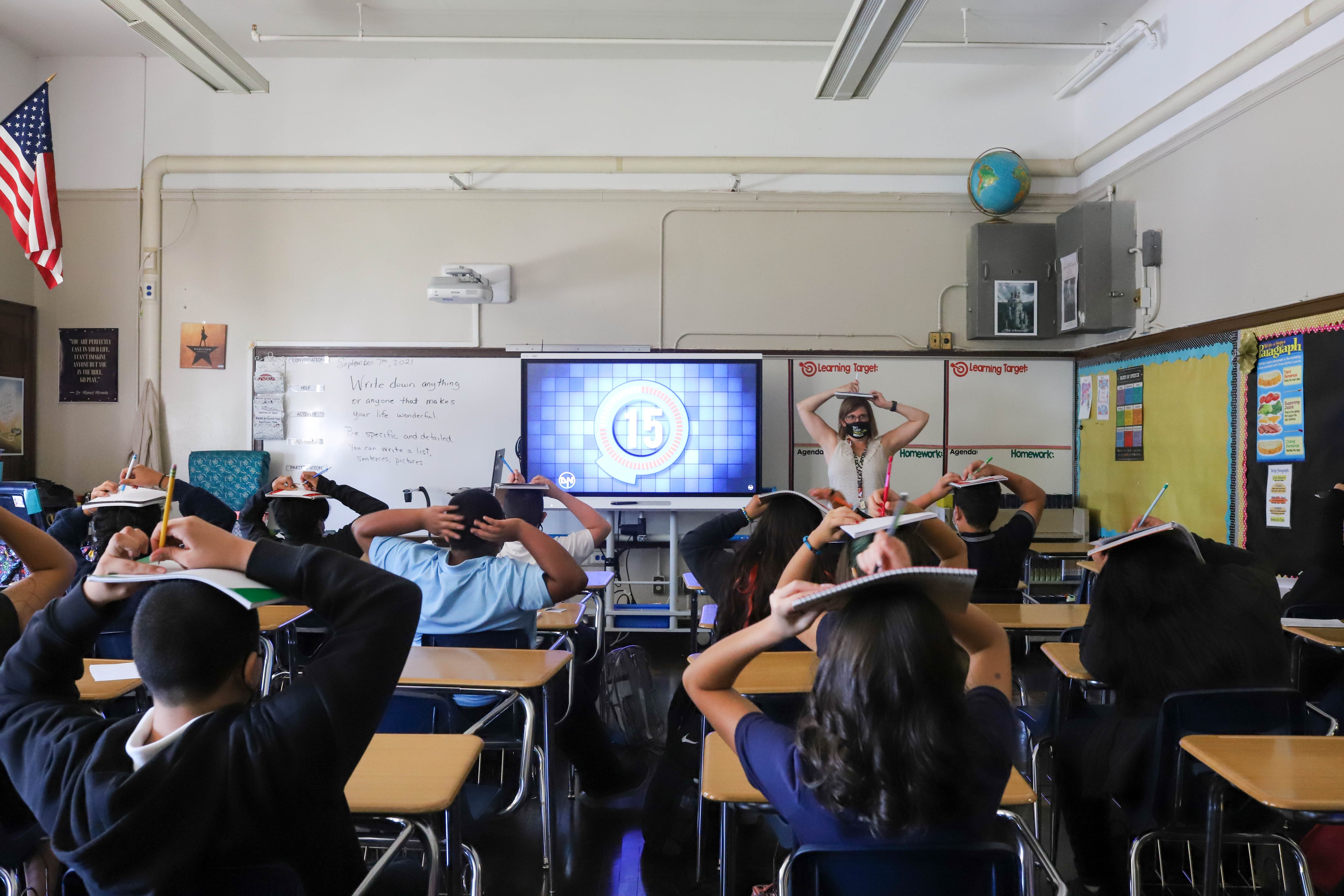

Joe Biden is not giving up on his signature education idea: providing schools with more money, particularly those serving lots of low-income students.

That’s the takeaway from the president’s latest education budget proposal, released Monday, which calls for more than doubling funding for Title I.

But recent history suggests schools shouldn’t count on this new money coming through. Biden got only a fraction of what he asked for last year, and it’s not clear there will be a path through Congress for this big budget increase, either — particularly since many forecasters expect Republicans to win additional seats this November.

“If we couldn’t get some of these priorities done when we had Democrats in the House and Senate and the White House, I’m not all that optimistic that this year is the year,” said Noelle Ellerson Ng, advocacy director of the school superintendents association, which backs Biden’s budget proposal.

The White House’s latest budget calls for allocating $36.5 billion to Title I, the longstanding program that sends money to schools serving students from low-income families and other disadvantaged students.

That’s the same amount Biden sought for Title I last year, though he ultimately got just $17.5 billion. But there are some indications that the Biden administration is scaling back its ambitions in response to the political challenges.

Notably, it separated the $36.5 billion request into two different pots: $16 billion in “mandatory” spending and $20.5 billion for “discretionary” spending, which is how Title I has traditionally been allocated. Reading between the lines, some see the $20.5 billion as Biden’s more realistic ask.

“It’s like, what’s your pipe dream budget and what’s your real budget?” said Ng.

In a budget briefing event, department official Roberto Rodriguez did not directly answer when asked why the administration had divided its Title I request. But he did note that $20.5 billion would still be a significant boost for Title I.

In another shift from last year’s proposal, the Biden administration is no longer suggesting it wants to rewrite the Title I formula or aggressively push states to overhaul their own funding formulas. (The administration does want to set aside $100 million for voluntary state and local commissions to “address inequities in school funding.”)

The administration is also calling for a significant increase in funding for students with disabilities, including grants to states under IDEA. Biden wants $18.1 billion for the program, an increase from $14.5 billion. Again, Biden called for a big increase in his last proposal; what was enacted was only a modest boost.

Meanwhile, the administration is calling for increases in spending on English learners, community schools, and teacher residency and grow-your-own preparation programs.

Biden is also pushing for $100 million for a new program to provide grants to communities seeking to integrate schools by race and class. This was proposed but eventually nixed in the most recent enacted budget.

And the administration is seeking $1 billion for a new program to expand access to mental health professionals in schools.

One program that wouldn’t get a boost under the Biden budget: money to help charter schools open and grow. But Biden isn’t seeking to cut the program, either. That represents something of a victory for charter schools, which Biden has criticized.

The National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, though, is still pushing for funding to increase, from $440 million to $500 million. “We had hoped that the President’s budget would have gone further and increased funding for the start-up, growth, and replication of high-quality charter schools,” CEO Nina Rees said in a statement. Notably, charter schools have significant support among Republicans in Congress.

If this budget proposal meets a similar fate as last year’s, Biden’s education department will find itself a funhouse mirror version of the Trump administration’s position. During Trump’s tenure, Secretary Betsy DeVos sought cuts to the education budget, but Congress largely discarded her proposals.

Ultimately, the vast majority of school funding comes from state and local sources, rather than federal ones, so the federal budget is not likely to make or break school district finances.

Matt Barnum is a national reporter covering education policy, politics, and research. Contact him at mbarnum@chalkbeat.org.