The world was warned about a rash of pneumonia-like infections clustered in Wuhan, China, about a week into 2020. By March of that same year, the novel coronavirus was declared a pandemic.

Since then, COVID has demanded a wide range of responses, from stay-at-home orders and shuttered institutions to mask mandates and testing protocols. More than two years into the global health crisis, our nation’s schools — teachers, staff, and the students and families they serve — are still dealing with challenges.

Chalkbeat journalists have documented the difficulties school communities have faced and are still facing. We’ve shared with our readers the chaos of school closures and re-openings, the mental health struggles of grieving and isolated families, and the staff shortages that many districts are confronting. We’ve also shared stories of resilience, success, and joy.

Here is a collection of our stories and photographs documenting the lived experiences of school communities during COVID.

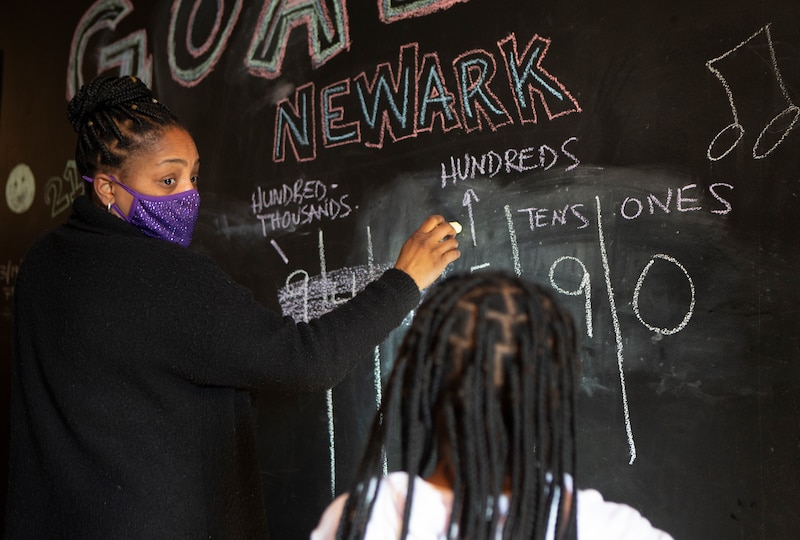

Newark: One teacher called, texted, and trudged through the snow to reach her students

Joicki Floyd, a ninth grade English teacher at Weequahic High School in Newark, watched COVID tear through the city where she was born. Floyd, 45, saw the disease strike down her neighbors and colleagues, adding to the list of COVID-19 casualties who were disproportionately Black and Hispanic.

Floyd kept teaching. She gave lessons over video, responded to students’ texts and emails late into the night, and trudged through the snow to track down teenagers who went missing. It became clear is that the skill she had sharpened over 20 years of teaching — her gift for connecting with students and drawing out their inner strength — had equipped her for this all-consuming crisis.

“This is what I do,” she said. “If I didn’t do it, I would feel frustrated. I would feel empty. I would feel like I’d be cheating my community and the children.”

Memphis and Detroit: Freshmen adjust to remote learning

Memphis student Jalan Clemmons struggled with remote learning during the pandemic. At one point, he discovered he was missing more than 70 assignments, but found a way to catch up after two months.

King Bethel, also a freshman and a talented singer and student at Detroit School of Arts, is used to being noticed for his voice. Inspired by a lesson about the history of redlining in Detroit, he used that voice to become a leader at the School of Arts, working on a speech for a public speaking competition called “Project Soapbox”

“I wasn’t trying to entertain,” he said. “I was trying to teach.”

Michigan: State’s ratings add stress for child care providers

Child care providers such as Linda Byrd and Shirley Wright were outraged that they didn’t get a reprieve from Michigan’s rating system during the pandemic, even as the state sought to pause accountability systems for K-12 schools. The state handed out fewer ratings overall — and fewer high ratings — to child care providers, our reporting found.

“My bills are not going to change because of this rating, but my money did,” said Wright, director of Little Scholars child care centers in Detroit, whose star rating dropped from a four to a three during the pandemic. “If education starts at birth, why do we treat early childhood education like it’s not education?”

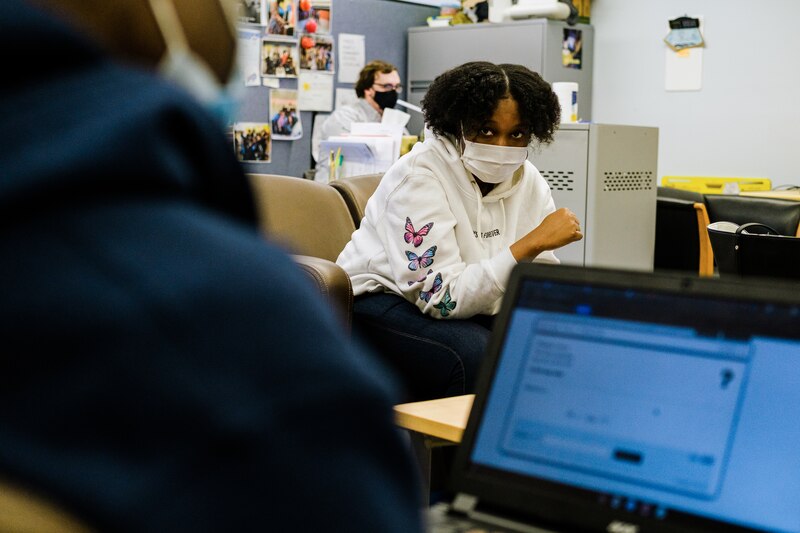

Brooklyn: Internship pays students to tutor their peers

Brooklyn high school freshman Alandinio Cineas was stumped by an algebra assignment asking him to write and graph an equation showing how many different pieces of fruit he could buy with $15.

He shared the problem on his computer screen with senior Chahima Dieudonne. The students were in the same room, but divided by a cubicle and logged into a virtual meeting. With masks pulled over their noses, they were close enough to hear each other speak but kept their distance to limit the chance of spreading COVID.

Dieudonne read the problem a few times and thought out loud, in both English and Creole. Then she and Cineas spent the next hour figuring out his math homework together.

Dieudonne is one of roughly 15 students at Brooklyn Community High School for Excellence and Equity who is paid through a school internship program to provide one-on-one peer tutoring to students like Cineas who need extra help.

Chicago: Parents help their children learn to read

Leslie Trejo, like most parents, doesn’t like playing the bad guy. But she accepted the role, if it gets her kindergarten daughter the extra reading practice she needs.

At Trejo’s home in Little Village, that means taking 15 minutes on Saturday afternoon to practice memorizing words such as “of,” “to,” and “was” — all while asking her third grade daughter to play nearby. The lesson: Fun comes after flashcards.

When COVID-19 forced schooling into the home, Chicago families like the Trejos found themselves suddenly on the front lines: watching, coaxing, teaching, and sometimes, throwing up their hands in frustration as their children tried to learn the basic building blocks of reading.

Chicago: COVID widened education gaps for boys of color

As the promise of spring hung over Chicago, three teenage boys tussled with insomnia, sifting through the fallout of a pandemic year’s interlocking crises.

Here and across the country there is growing evidence that the 2020-21 school year has hit Black and Latino boys — young men like Derrick Magee, Nathaniel Martinez and Leonel Gonzalez— harder than other students. Amid rising gun violence, a national reckoning over race, bitter school reopening battles and a deadly virus that took the heaviest toll on Black and Latino communities, the year has tested not only these teens, but also the school systems that have historically failed many of them.

NYC, Newark: A 360-degree look COVID’s impact on school communities

Chalkbeat, in partnership with Univision 41, took a deep dive into two school communities: New York City’s P.S. 89, and Newark’s Roseville Community Charter School. These two schools, both in neighborhoods devastated by the COVID pandemic, became lifelines for the communities they serve even as their staff dealt with the same challenges and loss as their families.

Through the experiences of educators, families, and staff, we captured how these communities adapted to the upheaval brought about by the pandemic, and how they laid the groundwork for recovery and a return to school buildings.

Detroit: My senior year in pictures

Through pictures and an original poem, titled “Fantasy Turns Into Reality,” Caria Taylor, a graduating senior at Detroit’s Cass Tech High School, gave a first-hand account of her journey in three parts: watching her creative voice blossom at the height of the pandemic, experiencing the joy of prom and graduation, and returning to some level of normalcy as she and her friends spend time together before they venture into adulthood.

Chicago: Graduation becomes a more significant milestone

“You made it through the pandemic,” Whitney Young Magnet School Principal Joyce Kenner told her students during their graduation on Chicago’s Soldier Field. “You can make it through anything.”

Across the country, graduating seniors from the Class of 2021 overcame unprecedented obstacles in receiving their diplomas. Our reporters documented these milestone events through students like Whitney Young Magnet senior Elijah Warren, and the graduating class of Indianapolis’ alternative high school Simon Youth Academy.

The Comeback: Aurora, Chicago, Detroit, New York, and Newark return to school

Over a year after COVID closed school buildings, students returned to in-person learning. This comeback brought mixed feelings to many families, who felt both relief and trepidation amidst the uncertainty of the pandemic.

Our journalists watched this return unfold in several districts around the nation, seeing the joy of children, educators, parents, and politicians as they welcomed learners back to the classroom. For some students, it was a return to a routine they hadn’t experienced for over 18 months. For other students, it would be their first time in a school building.

Newark: Bus driver shortage leaves students with disabilities behind

Maryah Santos, 14, listened as her mom tried to explain why she was stuck at home once again. School had started in early September and still no bus was headed to their home in Newark’s east ward.

“I love school so much, mommy,” Maryah said.

“I know, you love school,” Shannon Lutz told her daughter, whose intellectual disability makes it difficult to grasp why the bus hasn’t come and why she’s been home instead of reconnecting with teachers and classmates at school.

In New Jersey, where no virtual learning option was offered for the 2021-22 school year, 7,000 students like Maryah were either left without bus service or affected by last-minute changes to transportation caused by a shortage of school bus drivers that hit its peak in September, just as schools were reopening.

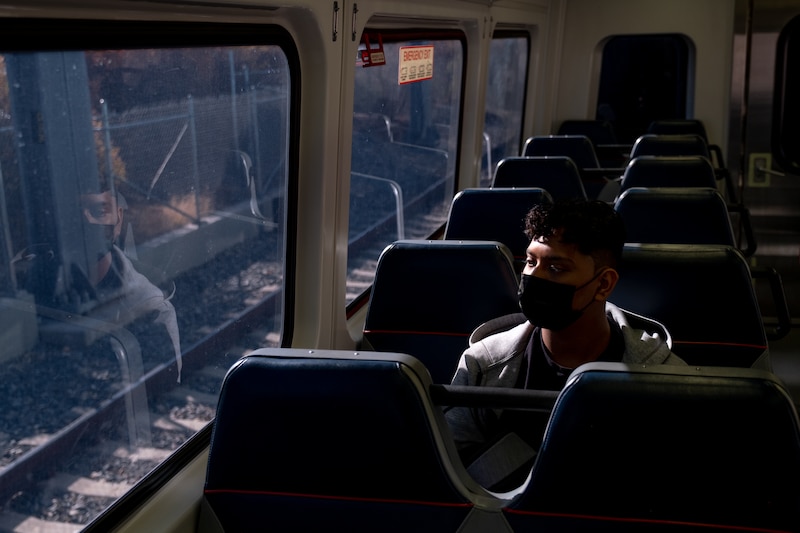

Colorado: Two Hispanic brothers wanted to go to college. Only one made it.

Jimy and Luis Hernandez’s alarm wakes them before the sun rises.

The brothers try to move quietly about their parents’ northeast Denver home so they don’t disturb their siblings.

Luis, 18, might watch the news or help his mom prepare lunch before they head to the toner cartridge factory where he works part-time to help pay for college. He’s enrolled at Metropolitan State University of Denver.

Jimy, 21, usually skips the kitchen as he hustles to get ready for his full-time job paving asphalt for a construction company. He wanted to go to college, but couldn’t navigate the path there.

The brothers’ divergent paths highlight the challenges Hispanic men face in getting into college — and in getting through.

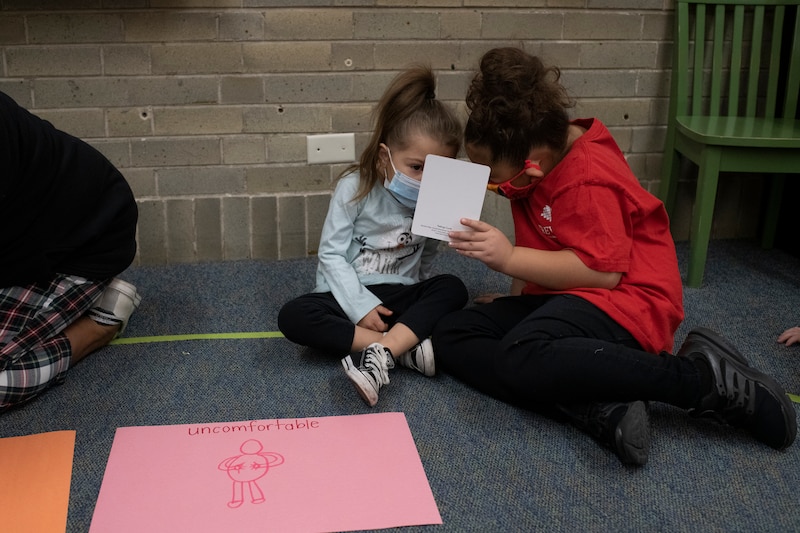

Denver: How schools prioritize social-emotional learning

The preschoolers in Natalie Soto-Mehle’s class have been talking about feelings.

“I’ve got some little cards with pictures, and we’re going to do a game with these,” Soto-Mehle, a teacher at Trevista at Horace Mann elementary school, explained to the 3-, 4-, and 5-year olds sitting on the rug. “But, before we do, we’re going to sing a new song.”

To the tune of “London Bridge is Falling Down,” she sang:

I have feelings, yes I do. Yes, I do. Yes, I do.

My body tells me how I feel,

Feelings in my body.

Lessons like this are what schools call social-emotional learning, which teaches students to be emotionally resilient, form supportive relationships, and develop healthy identities. As Denver Public Schools transition back to in-person learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, the district is requiring each school to offer 20 minutes of daily social-emotional learning to help students face mental health challenges brought on by two years of pandemic living.

NYC: Parents accused of educational neglect for keeping their children home

After spending last year fully remote, Viviana Echavarria’s two teenagers were excited to return to Riverdale Kingsbridge Academy and even went back-to-school shopping.

But then the Bronx mom and her husband decided to keep their two high schoolers home until their 11-year-old could get vaccinated.

Still, Echavarria was stunned when her husband called late last month while she was at work, as a director of operations for a nursing home, to tell her that an ACS caseworker was at their door. He hasn’t returned to work yet in order to stay home with their three school-aged children and 6-month-old baby.

When New York City opened its schools this fall for in-person learning, with no option for virtual instruction, families across the five boroughs opted to keep their children home. Families like the Echevarrias worried about the health of their children and vulnerable loved ones, and remained unconvinced it was safe to return to school.

Philly: Reading lessons at the laundromat

On a cold Saturday afternoon, Iris Hernandez and Carmen Colon were helping six Morales children through the letters, sounds, and words in the book “DJ’s Busy Day,” about a bunny and his fun-filled adventures in ordinary places: the grocery store, on the bus, in his home. Their lessons took place in a local laundromat.

Hernandez and Colon are reading captains working with Global Citizen, which has been leading a community mobilization in partnership with the Philadelphia Public Library’s Read by 4th initiative, a citywide drive to help all children read proficiently by the end of third grade. Some research shows that early reading proficiency is linked to high school graduation.

The city still has a long way to go toward its goal. Before the pandemic, standardized tests showed that only about a third of children in district schools read at grade level by fourth grade.

Philadelphia: One school’s new normal in its second COVID winter

Nearly two years into the pandemic, COVID often blends into the background at Cayuga Elementary School in North Philadelphia.

Other times, COVID is painfully obvious. In January, a little boy told kindergarten teacher Ruth Llorens he missed his uncle, who’d died from the virus over winter break.

“I just kind of listened to him more than anything else,” she said. “Really, he just wanted to talk about his uncle and what they used to do.”

Such is the year so far. Routine classroom moments are punctuated by reminders of COVID’s fallout, ranging from sadness and fatigue to the recognition that some students missed out on lots of learning over the past two years. That includes academics, of course, but also classroom routines.

Chicago: One high school’s year of uncertainty

For schools across the country, this school year was supposed to be the moment to recoup academic ground lost during the pandemic and tend to the outbreak’s traumas before high school careers and lives got derailed. It was supposed to be a time to start reinventing public education for teens like Richards High School senior Keshaun Arnold and the other students Richards serves: half of them Black, another half Latino, almost all from low-income families, a third learning English as a second language, and another third without a stable place to live.

It hasn’t turned out that way.

At Richards, a tough comeback has overwhelmed the students and staff. Attendance is down. Behavioral issues are up. COVID has waned and surged, exploding any semblance of certainty.

Such setbacks have played out across the country, in district after district, at school after school. Here and elsewhere, amid a race to re-engage students in learning, the desire to find new ways of approaching school has collided with the need to just make it through another trying week.