In January of last year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention mischaracterized an outside study about school reopening. The researcher emailed the agency to complain, but the error was never corrected.

In fall 2021, a CDC study acknowledged that it could not identify the direct effects of masking on COVID spread in schools. The agency nevertheless claimed the study supported the need for universal masking.

And just a few months ago, the CDC failed to clearly describe how revised masking guidance applied to young children, causing significant confusion. The agency’s pages for schools and childcare centers still contain outdated information.

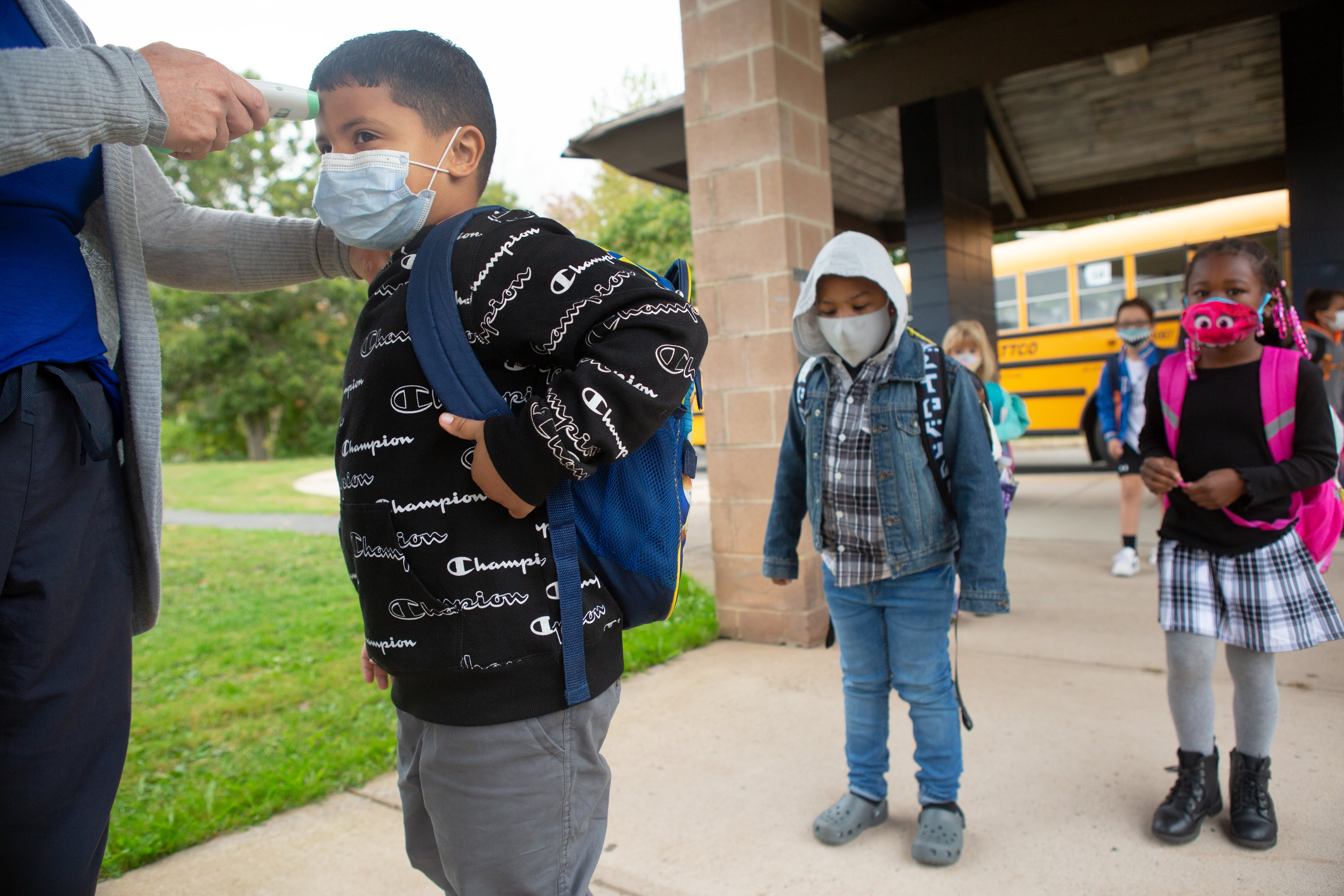

Many have debated the substance of the CDC’s recommendations to schools throughout the pandemic. But a Chalkbeat review suggests that over two years, the agency fell short at a more straightforward task: to communicate clearly and accurately with schools about its guidance and research.

The CDC did not respond to requests for comment about a detailed list of concerns.

Those missteps have left school officials without a precise sense of the benefits and downsides from different mitigation measures, including masking. In other cases, officials missed or disregarded CDC guidance because it was unclear or overly complex.

“Every step along the way, the communication has been very bad,” said John Bailey, a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and author of a newsletter about the pandemic and schools.

“They had a really hard job. This has never happened before in anybody’s lifetime,” said Doug Harris, a Tulane University researcher who has studied schools through the pandemic. Still, he said, “The quality of research coming out was disheartening.”

Dubious research

The CDC has played a central role in publishing and disseminating research related to schools and the pandemic. Its “Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report” is meant to produce “timely, reliable, authoritative, accurate, objective, and useful public health information and recommendations.” The agency’s press and social media arms often spotlight specific studies, drawing media attention.

And yet much of the research the CDC has released and promoted is strikingly limited, even flawed.

Take the issue of masking. Remarkably, two years into the pandemic, there is little definitive research on either the benefits or the downsides of requiring masks in American schools, even though the CDC has released a number of studies on the topic.

For instance, one paper compared COVID rates in schools with and without required masking in Arizona, but didn’t adjust for vaccine levels, testing rates, or other safety precautions in schools that might explain differences between schools. “If you’re really going to assess the utility of masking, you’ve got to control in any study for all those other things,” said Susan Hassig, a Tulane epidemiologist.

Another CDC study using national data found pediatric COVID cases were higher in counties without school mask mandates — but the authors admit at the end that “causation cannot be inferred” from their study. That is not a small caveat. If the studies could not establish the effect of masking, what exactly is the point?

Nevertheless, CDC promoted these results, suggesting a direct link between masks and COVID spread. “New [CDC] data reinforce the benefits of masks and vaccinations in preventing #COVID19 outbreaks in schools,” Director Rochelle Walensky tweeted about the Arizona findings.

The CDC also published a dubious analysis suggesting that COVID-19 increased diabetes risk in children. Again, the paper failed to account for other factors that might explain diabetes rates.

“They were releasing and even highlighting a lot of studies that were pretty correlational and not very convincing,” said Harris.

Jay Varma, who was previously a health advisor for New York City, says clear information on the effectiveness of different mitigation measures would have been especially helpful — but was lacking. “What if I do this ventilation technique? What if I try this masking approach? What if I do this distance?” he said.

In other instances, the CDC simply mischaracterized research evidence.

In March 2021, the agency announced an important shift to its guidance: it was relaxing recommended distancing in schools from six feet to three feet. In an accompanying scientific brief, it claimed that COVID transmission in schools was low “even when student physical distancing is less than 6 feet.” One piece of evidence was a Florida study that purportedly showed that COVID spread was higher when fewer students were learning in person.

In fact, the study showed exactly the opposite, undermining the new guidance. After Chalkbeat inquired about this discrepancy, the CDC quietly corrected its brief but did not change its characterization of the overall research.

In another case, the CDC published a paper in early 2021 that mischaracterized research by Harris and Hassig, who found that school reopenings did not contribute to hospitalization rates when COVID spread is low to moderate. But their study could not make firm conclusions about school reopening when case rates were high.

The CDC paper described the first part of the results but omitted the second part. “I emailed them immediately — you’re missing the whole point of the study,” Harris said. The CDC never corrected its report, and the misleading reference remains.

A lack of clarity

The CDC has also struggled throughout the pandemic to provide clear guidance to schools.

The agency did not get off to a good start on this front. The agency issued guidance in May 2020 about reopening schools. But the brief “decision tree” included little more than obvious tips like complying with local health guidance and ensuring those who are sick stay home. More detailed guidance was reportedly suppressed by the Trump administration.

Over the summer, the CDC issued additional guidance, but it was often contradicted by Trump himself, who criticized the agency’s approach.

“Unfortunately, at the time where the guidance was most needed, it was least available,” said Sasha Pudelski of AASA, the school superintendents’ association.

Recent communication challenges cannot be blamed on the Trump administration, though.

In summer of 2021, the CDC released a new round of detailed recommendations for schools on masking, quarantines, and distancing. But by fall, it was clear that a crucial part of that guidance had not been widely followed.

Throughout, the CDC highlighted the need to quarantine “close contacts” — generally defined as people who were within six feet for an extended period of someone who contracted COVID.

In a confusing but crucial caveat, the guidance instructed readers to “see the added exception in the close contact definition.” On a separate page, the agency noted that for students in K-12 schools, the threshold for a close contact had been lowered to three feet if students were masked.

This guidance didn’t seem to trickle down, possibly because it was not widely publicized and was hard to find and understand. (Chalkbeat even created its own guide to help confused school officials.)

“Districts do not appear to be following CDC quarantine guidelines, which while unclear, do recommend that masked students be exempted from quarantine — a less rigid recommendation than we are currently seeing among most districts,” noted analysts at the Center on Reinventing Public Education in August 2021.

As the school year began and the delta variant raged, precautionary quarantines were widespread and schools struggled to help students continue learning. Many of those quarantined might have been unnecessary if the CDC’s guidance had been understood and adhered to.

This February, the CDC issued another update to its schools guidance. This time, it recommended that schools and child-care centers make masks optional when community COVID levels are low to moderate.

Most K-12 school officials got the message. The update specifically mentioned K-12 schools, and the change garnered widespread media coverage. But the takeaway was muddled for providers of early childhood education and childcare, which were not specifically mentioned in the new guidance.

Economist and influential commentator Emily Oster wrote an article for The Atlantic based on the assumption that the CDC was still recommending masking for young children. She learned this was incorrect only after someone with the CDC reached out to her directly.

“There is a fair amount of people looking to this guidance and trying to interpret it and the way that it is currently stated is extremely difficult to interpret clearly,” Oster told The 74.

Despite new guidance being issued months ago, CDC’s pages for schools and childcare centers still contain outdated information, including a reference to “universal indoor masking.” On its site, the agency notes that it is in the “process of updating this page with these new recommendations.”

Matt Barnum is a national reporter covering education policy, politics, and research. Contact him at mbarnum@chalkbeat.org.