Kurt Russell’s path to teaching was forged in his eighth grade math class.

It was there he met Larry Thomas, an energetic and tenacious educator who was also Russell’s first Black male teacher.

Russell liked that Thomas worked to connect with him over shared experiences, such as the fact that both of their families had migrated to Ohio from Alabama. He also admired how Thomas made math class relatable, like asking students to calculate an average using a famous basketball player’s performance statistics.

“He brought that cultural connection,” Russell said. “I just fell in love with him.”

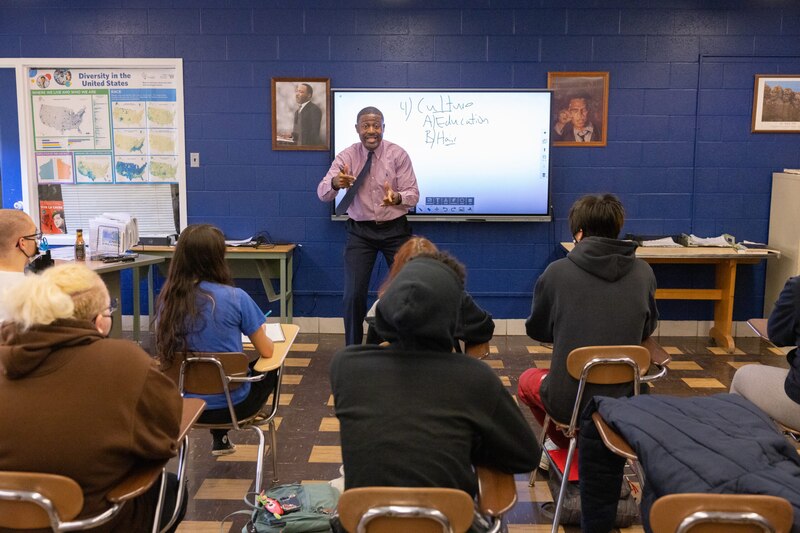

That approach has stuck with Russell, who has taught history for more than 25 years in Ohio’s Oberlin City Schools, the same school district he attended as a child. Russell now teaches U.S. history, as well as courses he created on African American history and race, gender, and oppression. And it was his own work to connect with students and reflect their experiences in his lessons that helped earn Russell the title of National Teacher of the Year on Tuesday.

“We are living in a time when our students need conscientious teachers more than ever,” Russell wrote in his application, noting his parents attended segregated schools in the Jim Crow South, where Black students were denied basic resources at school, a disparity that still persists today. “While I cannot alter time or reverse past practices or policies, I can help construct opportunities for students of all races, ethnicities, religious affiliations, and gender identities.”

Chalkbeat talked with Russell about how teaching in his hometown allows him to forge deeper relationships with his students, why he created a history class focused on race, gender, and oppression, and what it’s been like to teach history at a time when lawmakers across the country, including in Ohio, are moving to restrict how race and racism are taught in schools.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What has it been like to come back and teach in the community you grew up in? How do you bring your own history to your lessons?

I always wanted to come back to Oberlin to teach, just because of what teachers in the community instilled in me. I’m able to connect with students because I’m connecting with their parents now, I’m connecting with their grandparents. I know them well.

I’m able to mention things that happened in Oberlin in a historical context. Oberlin is a hotbed for the Underground Railroad — we were Station No. 99. And there are several houses in Oberlin, on a street called College Street, that has the cellars where enslaved Africans were kept as they made their journey to Canada. As I mentioned these homes, students are like ‘Wow, I know that house!’ Students make a connection that way.

Can you tell me more about when you started teaching your race, gender, and oppression history class? What were you hoping students would take away from the class?

I started teaching that course maybe 13 or 14 years ago. Students came to me and said: Mr. Russell, are there any other courses that you teach? Because we want a little bit more than the typical U.S. history class. So I borrowed from my college first-year seminar. I believe the title was ‘Racism and Sexism in America.’ I said: You know what, I have readings from my college days, I have the syllabus, let me tweak it a little bit.

Right now, it’s still an elective, but it’s probably one of the most popular courses in the school because students see themselves in the lessons. We have topics such as the LGBTQ+ community, a Black Lives Matter unit, a women’s studies unit. A lot of the topics that we teach, students are able to see themselves, and they can create a narrative through their own stories.

Are there certain lessons that have been very engaging for students that you’ve noticed: ‘Wow this lesson really hit home for students’?

Every year as we study the LGBTQ+ unit, as we study Title IX, there is always a question that deals with: Should transgender students participate in athletics? Students really engage in that particular conversation because it’s current information. You see it on the news all the time, you see it in readings all the time.

In my classroom, students are, I wouldn’t say polarized, but they have different opinions. Which is great. But they’re able to have a discussion that’s respectful.

We set norms in my classroom, and we create a safe environment. Our norms are very basic: We will respect other people’s opinions. We will listen. Anything we say in the classroom stays in the classroom.

That’s what I really appreciate and really love about the class — it’s a microcosm of the United States of America. We are on the opposite sides on some of these hot topics, but should be on the same side, in terms of having respect for one another.

We’ve seen legislatures across the country putting restrictions on how race and racism can be taught. In Ohio, the legislature is considering some bills that haven’t passed, but would restrict talking about ‘divisive concepts.’ For you, as a history teacher, what has it been like to teach under that shadow?

My community, my students, and my school accept diversity within the curriculum. Even with some of the backlash, my students are more eager to learn, and my school district is more eager to put forth a more diverse curriculum. On a national and on a state level, you have individuals who may not agree with me, or with Oberlin City Schools, in teaching some of the subjects that are being taught.

Do your students bring up what’s happening at the state legislature in class? Have you had discussions about: Why are state legislatures considering putting laws in place that would change how history is taught?

Yes, they do. Especially in my race, gender and oppression class, we do readings and we watch TED Talks, and we watch news footage of discussions on these topics. Students just want to know more and more about it. It’s allowed my students to be more conscious about what’s happening and to voice their own opinion.

I know you helped create, along with other educators and students, the Black Student Union at your school a couple years ago. Can you say more about why you and others thought it was important that your school had this group?

After the untimely murder of George Floyd, two students said: Mr. Russell, we need to do something. They thought about creating a club. I belonged to the Black Student Union in college, we had some bylaws, and I shared that with my student group. And they took the initiative to run with it. We’ve met with the police chief, and with police officers, and resource officers, discussing that town-and-gown relationship. It has just made Oberlin High School a better place.

Kalyn Belsha is a national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.