When the Oregon Department of Education announced that it would allow students to record their gender as “X” instead of “M” or “F” in its state-level systems, Corvallis School District changed its own system to match.

But when the time came to report enrollment to the federal Office for Civil Rights, Corvallis encountered a problem. The mandatory Civil Rights Data Collection didn’t allow districts to report nonbinary students, just males and females.

Corvallis’ assistant superintendent, Melissa Harder, recalled receiving an email from the data specialist in the finance department: “The federal government wants me to make a decision on whether or not a student is male or female. And I don’t think I should do that.”

Several districts across the country have faced the same dilemma. But that might be about to change, as the federal Office for Civil Rights has proposed expanding its data collection to include nonbinary students for its 2021-22 report, for which submissions begin this December.

If that change happens, it wouldn’t require school districts to collect this data. Still, it would be a significant step toward assembling data on nonbinary students across the U.S. Already, at least 10 states, plus the District of Columbia, allow districts to report a third gender category, and some districts like Denver Public Schools collect that information on their own, too.

Researchers with LGBTQ organizations say that data is crucial to understanding the school experiences of nonbinary students, who report high rates of harassment, bullying, and other forms of targeted discrimination.

Still, it remains unclear how useful the data would be in its early forms — and advocates, researchers, and school officials say even with federal support, districts who want to offer additional gender marker options will still have to navigate disjointed systems that define gender differently.

Why federal data matters

The Office for Civil Rights has required public schools to submit data to the Civil Rights Data Collection every other year since 1968. The exact content changes regularly, but data from the collection has been used to analyze chronic absenteeism, sexual assault, school safety, harassment, and bullying.

The Office for Civil Rights also uses data from the collection to investigate discrimination allegations, review whether schools are addressing nationwide civil rights problems, and develop policies and guidance for administrators. For instance, the office recently quantified continued widespread use of restraint and seclusion for students with disabilities.

Adding nonbinary students would include data on any LGBTQ students for the first time, though the data would still not reflect transgender students who are not nonbinary or LGBTQ students more broadly.

Joseph Kosciw, who directs the research institute at the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network, said that the CRDC’s expansion could help answer important civil rights questions, which are currently difficult to research for nonbinary students.

“You want to see — as we do around other identity characteristics — how is school safety? And how is access to education?” he said.

Not everyone agrees the data would be useful or appropriate to gather. Parents Defending Education, a small grassroots group known for opposing critical race theory, objected to the proposal, saying it would “empower schools to actively question and engage with children on gender and sexual identification issues that fall outside of the purview of public schools and are matters to be dealt with exclusively by parents.”

Others are concerned about whether districts can responsibly collect data on nonbinary students. Student privacy advocates at the Center for Democracy and Technology have raised concerns that schools may need more time to consider nonbinary students’ safety and privacy — especially considering the recent flurry of laws passed in Florida, Texas, Alabama, and other states, which restricts LGBTQ+ curricula, trans athletes’ participation in school sports, or transition-related health care.

“This information can be powerful, but also, you have to be just as protective of those students’ rights and make sure that information can never be used against them,” said Elizabeth Laird, the center’s director of equity and civic technology.

The center also noted, like GLSEN and other organizations, that collecting only data on nonbinary students could mean missing important information about harassment of transgender students.

If the changes do happen, districts that don’t already let nonbinary students use an X gender marker could skip that section when the data is first collected. In the future, all schools would be required to fill out something for nonbinary student enrollment, even if they just indicate that they don’t collect it.

The Office for Civil Rights did not respond to multiple requests for comment on whether it has specific goals for future data on nonbinary students or whether it anticipates the number of nonbinary students will be large enough to analyze.

But the office’s statement on the proposed changes argues that the new data would help identify discrimination and “provide a greater understanding of the experiences of nonbinary students.”

To Damien Lopez, the CRDC’s proposal would bolster organizations like Garden State Equality working to improve school experiences for LGBTQ students in New Jersey.

Lopez helps train New Jersey school staff on state law and general best practices for working with LGBTQ students through Garden State Equality’s Safe Schools & Inclusive Curriculum program. In his work, Lopez sometimes hears calls to support trans and nonbinary students dismissed due to limited or nonexistent data at the school level.

“People will say, ‘Oh, but there’s not really those students in the classroom.’ But you don’t know that unless you report the numbers,” Lopez said. “The more that we acknowledge that trans kids are there, then the more that we can support them and create a safe environment.”

Getting an accurate picture

New Jersey is also one of the dozen states currently collecting nonbinary student enrollment numbers. Its most recent tally of nonbinary students statewide: 85.

But estimates from academic research centers suggest there are potentially several thousand trans or nonbinary students in New Jersey. The difference makes Lopez concerned that not enough schools are creating safe environments for nonbinary students to come out.

“It’s sad to see,” Lopez said.

Researchers and experts widely say that they expect school-based initiatives to undercount nonbinary students, and there isn’t a good nationwide estimate of how many nonbinary K-12 students are in schools right now.

The Trevor Project’s 2021 survey of 35,000 LGBTQ youth ages 13-24 found that one in four LGBTQ respondents identified as nonbinary, regardless of whether they also identified as transgender. The Williams Institute also consistently estimates that roughly 0.75% of youth ages 13-17 are transgender, but does not estimate how many LGBTQ+ students are nonbinary.

State youth health surveys, which allow students to anonymously self-identify without making any official changes in their records, often find higher rates of trans and nonbinary youth than other sources.

Survey methods differ between states, so they’re hard to compare; some combine trans and nonbinary student data, while others ask for those identities separately. Across 10 states, anywhere from 1% to 12% of high school students indicate they are transgender, nonbinary, or gender-expansive in these surveys. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that, based on state health surveys in 2017, an average of 1.8% of high school students reported being transgender, specifically.

Some districts, like Chicago Public Schools, have used these youth health surveys to examine health disparities for LGBTQ+ students. That approach has brought Chicago some of the best data they currently have, according to the district’s LGBTQ+ and Sexual Health Program Manager Booker Marshall. But it still has limitations, and Marshall thinks the federal data might offer a clearer picture.

“It’s interesting to be able to get at a federal level — potentially — official numbers on nonbinary students,” they said.

At the same time, Marshall said, any new research from the CRDC would only reflect nonbinary students who specifically want to change their gender marker within their districts’ records — which isn’t everyone. Some nonbinary students who use a chosen name and pronouns with their teachers and other students aren’t interested in using the district’s X gender marker, Marshall said.

“The federal government wants me to make a decision on whether or not a student is male or female. And I don’t think I should do that.”

Crucially, those low numbers could also make the data difficult or impossible to interpret, especially at first.

Newly introduced CRDC data can be tricky to analyze, since not all districts collect and report it, according to American Institutes for Research Principal Researcher Stacey Bielick. Bielick works with the National Center for Education Statistics to improve the quality of the CRDC data.

Researchers may need to take creative approaches to analyzing and aggregating the data, she said.

“It will eventually come into its own, but initially, there’s going to be some issues,” Bielick said.

To Marshall in Chicago, the quality and usability of the data isn’t the only important consideration.

Even if the data isn’t perfect, they said, “It is a big deal to have nonbinary gender affirmed federally for young people.”

For districts, change is complicated

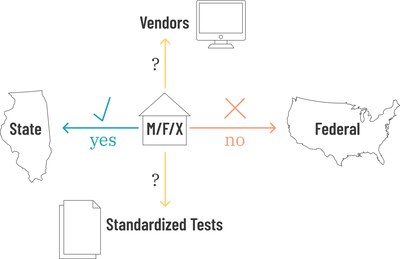

If the federal government allows districts to report nonbinary students, it will be the last piece of the puzzle for school officials in Corvallis, Oregon, where the district and state data systems already allow it.

But for many districts, attempting to add that option means getting tangled in state or proprietary systems they don’t control.

Boulder Valley School District in the Denver suburbs has had a detailed anti-discrimination policy covering transgender students in place for 10 years, and the U.S. Department of Education and the U.S. Department of Justice pointed to the district’s policies as an example of best practices.

Even so, students can’t yet list themselves as nonbinary in their records. A representative for the district said that the IT team is still waiting for the state to make changes to its data collection or student information systems.

Ridley School District, which serves about 5,500 students in the Philadelphia suburbs, reports similar limitations.

“Our student information system doesn’t currently give us access, and that gets updated by the state requirements,” explained Superintendent Lee Ann Wentzel. “We would have to follow the state’s lead.”

Philadelphia itself added the option for students to identify as nonbinary on its virtual education platforms last year. The state system has a new field to report gender identity.

But Wentzel said that her smaller district could not afford to independently make system-wide changes to how students report the data to their schools. If the Pennsylvania Department of Education required vendors to add a new nonbinary option, her district could use it. Otherwise, Ridley would likely have to report to the CRDC that her district doesn’t collect nonbinary student information, she said.

Wentzel is also a member of The School Superintendents Association, which has been urging the Office for Civil Rights to streamline, rather than expand, federal data collection.

The association questioned in a public comment whether nonbinary student data will be usable or accurate “until we have more flexible state policies that enable and encourage districts to collect and report this data.”

Ongoing changes in Denver and Chicago

Meanwhile, districts who have already made these changes say that they are still navigating how their schools’ systems interact with other platforms.

A Chicago Public Schools official said the district’s Title IX office requested that the CRDC add an option for nonbinary students after the district launched a customized student information system in 2019. Illinois added a similar option this school year, according to the state board.

“It’s difficult for us to navigate when systems are not accepting affirmed names and nonbinary gender markers, because that’s not aligned with our system,” said Marshall, who has coordinated the district’s effort to sync its internal systems with its trans-inclusive policies. “It takes a lot of testing, and a lot of time and resources, a lot of people to implement these changes.”

Denver Public Schools has been grappling with similar problems since it modified its student information system in July 2021. The changes were in large part prompted by online learning systems during the pandemic, according to Levi Arithson, program manager of LGBTQ+ equity initiatives at the district.

Students who went by different names in class were suddenly interacting through online platforms that display students’ legal names. Arithson said schools started contacting him about students having issues with the system.

“Oh, we need to figure this out — now,” they recall thinking.

The initial changes took about four weeks to implement, according to DPS’ product integration team. But the team estimates it researched the options for about two academic years first.

Students can now select from six gender categories — male, female, nonbinary, transgender, other, and prefer not to answer. The district also uses an extensive toolkit to help LGBTQ students understand where their name and gender marker changes show up.

Denver’s primary student information system, Infinite Campus, offers nonbinary student options. Around 650 districts across the country have enabled options besides M or F in Infinite Campus, according to CEO Charlie Kratsch, though that covers a wide range of gender identifiers and includes “other” or “unavailable.”

But adding more specific options can bring complications, too. Officials with both Chicago and Denver say they have had issues with legal names and preferred names not aligning on standardized tests run by the College Board, which administers the SAT and other exams. Mismatches between the districts’ data and the systems that absorb it can cause unexpected problems, like difficulty matching students with the correct accommodations for their disabilities or their test scores.

According to Arithson, it’s an ongoing process to balance these technical changes with students’ needs.

“It’s hard to say, ‘Well, I’m considering students first’ if there’s some type of data complication and the student is getting lost,” they said. “But in my mind, these students have waited long enough to get what they need to be able to feel seen in school and to feel like they can be themselves.”

Product manager Marc Long said the Denver Public Schools product integration team is still working behind the scenes with vendors and other systems to make sure students have a smooth school experience.

“We cannot dictate to other governmental agencies or to third-party vendors what they accept from us as a value,” said Long. “If they require an M or F in the field, we can send them another value, but then they literally just don’t have to consume what we send.”

Right now, Denver sends students’ legal gender markers to the state and federal reporting systems. But the CRDC’s proposed new definition of “nonbinary” wouldn’t line up with Denver’s six options. Long’s team would have to decide whether to combine multiple markers under the federal X, or take another route. Similar problems have taken anywhere from several hours to several weeks for them to address, according to Long’s manager.

To Arithson, the challenges are worth the payoff, and a federal policy change might encourage some of the educational technology vendors to catch up with students’ needs.

“The systems are outdated and they need to be updated,” he said. “We’re human beings living in bureaucratic systems that move slowly. What do we need to do for them to see us and our humanity?”

What type of coverage of LGBTQIA communities in schools is the media missing? Let us know in our short survey.

Kae Petrin is a data & graphics reporter for Chalkbeat. Contact Kae at kpetrin@chalkbeat.org.