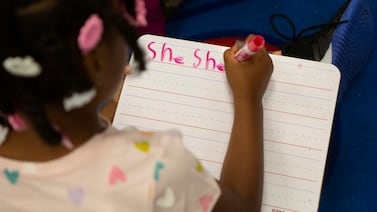

American schools have suddenly found themselves at the center of several fierce cultural debates, particularly related to race and racism. The stakes are high — both politically and educationally.

So what do American voters and parents actually think about these issues? It can be hard to get a good sense of that amid an avalanche of anecdotes, news stories, and viral videos.

Chalkbeat examined over 20 polls since last year to find out. In some cases, what we found was surprising, while others confirmed conventional wisdom. And there were instances of both widespread agreement and sharp division.

There are real divides in this country on how to teach about race and racism, particularly on whether to teach about racism as a present-day phenomenon. Parents are also divided about whether schools pay too much or too little attention to race and racism.

But most parents surveyed also say their child’s school does a good job keeping them apprised of what’s taught in class. More broadly, most Americans agree on certain issues: that schools should teach about the history of slavery and racism, that books shouldn’t be banned for political reasons, and that schools shouldn’t divide students by race for class discussions.

Keep in mind that polling provides only a snapshot of opinion, and results can shift based on question framing, political messaging, or the arguments of one side or the other. That said, here are several important takeaways from these surveys.

There is a fundamental divide among Americans on whether schools should focus more or less on race and racism.

Perhaps the simplest way of understanding the clashes over schools is the question posed in a recent Associated Press poll: “Do you think your local public school system is focusing too much or too little on racism in the U.S., or is the focus about right?”

Divisions were clear: 37% of Americans said about right, 34% said there was too little focus, and 27% said there was too much. In other words, a majority of adults believe schools need to change the amount of focus — but they diverge on what direction they should go. This split is echoed in other polling too, including surveys of parents.

There are really big racial and political differences on these issues

Divides about schools break sharply along racial and political lines. Democrats and people of color tend to support a stronger focus on race in schools; Republicans and white Americans tend to be much more skeptical of focusing on race. This pattern shows up in poll after poll in mostly predictable ways, including a national poll about how much schools should teach about racial inequality.

Critical race theory is not popular, but there are moderate levels of support for teaching about the present-day effects of racism.

The academic framework known as critical race theory has morphed into a catch-all term for conservative critics on the right to refer to practices in schools relating to race that they oppose. Unsurprisingly, it typically doesn’t poll all that well (although many people say they’re not sure what it means). At the same time, discussing the present-day effects of racism does draw meaningful, although not overwhelming, support. You can see the disconnect in a poll of Missouri voters.

In a national poll, a slim majority of Americans held negative views about critical race theory. (The academic framework of critical race theory probably is rarely taught in schools, although it has informed practices in some school systems.) At the same time, three-quarters said that public schools should “be allowed to teach about ideas and historical events that might make some students uncomfortable,” and even more opposed banning books in schools.

Another poll found that 53% of voters believe it’s appropriate to teach high school students that “systemic racism is embedded in American institutions,” while 46% say it’s not appropriate.

Americans more broadly agreed that schools should teach about slavery and racism as a historical matter.

Notably, though, people seem to have somewhat less appetite for frank discussions about race and racism in early grades.

Polling is mixed on a variety of racial equity efforts.

Some are quite unpopular. For instance, one poll found that 51% of adults favored tracking students by ability level, even though the question said that some fear that this will exacerbate racial inequities. Only 19% opposed tracking.

Another survey asked about grouping students by race “to encourage students to discuss their experiences with others who share their racial or ethnic background.” 76% of voters described this practice as harmful.

Most Americans of all races also favored using standardized test scores as a part of college admissions, despite recent pushback that these tests discriminate against Black and Hispanic students. And most also opposed race-based preferences in college admissions.

But polls show significant support for ideas like having students read a racially diverse set of authors or learn more about Black history. In one survey, 60% of public school parents said students should be encouraged to “read books by authors from a variety of different racial and ethnic backgrounds.”

There does not appear to be a widespread parent belief that schools are focusing too much on racism.

One poll found a plurality of parents, 40%, believed “schools are handling issues related to race and racism about right.” That was notably higher than the general public. Another 29% said schools aren’t focused enough on these issues.

In another recent survey, only 19% of parents said that the way their child’s school teaches about racism was inconsistent with their own values. 38% said the school’s approach was consistent with their values and another 32% weren’t sure.

The vast majority of parents also said their child’s school does at least a decent job keeping them abreast of curriculum on controversial topics, according to multiple polls.

Throughout the pandemic, most parents have expressed general satisfaction with their child’s school.

Democrats still have an edge on education issues — but it’s shrinking

All these issues are deeply linked with politics. After Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s upset win last year, Republicans have been on the offense on education issues. Many see attacks on critical race theory or too much attention to race in schools as a winning issue for this November.

But voters continue to trust Democrats on education issues more than Republicans, according to multiple polls. In one, 44% said Democrats’ values on education more closely align with their own, compared with 34% who favored Republicans. Parents gave Democrats a 5 point edge.

Another recent survey found a several-point advantage for Democrats, but showed that it had dipped since 2019, and was at its lowest point in many years.

Matt Barnum is a national reporter covering education policy, politics, and research. Contact him at mbarnum@chalkbeat.org.